Incarceration represents a complex and challenging environment, particularly for young men. Prison culture often demands the adoption of certain masculine ideals, specifically masculinity in prison, that can hinder the process of trauma recovery.

Background

This article presents the key findings from a comparative study conducted on a cross-national sample of young Canadian and Scottish men from six different prisons in Canada and Scotland. The aim of the study was to explore the adjustment and experiences of young men ages 18–24 in two different systems for young adults: Canada, where young adults are housed in adult institutions with no specific young-adult regime, and Scotland, where a specific facility and regime for young adults are present. The analysis and results in this article, published in Men and Masculinities, Volume 26, Issue 2, 2023, arose from findings that were not the focus of the main research project but subsequently became an area of interest.

The study sheds light on the prevalence of trauma, the role of masculinity in prison, and the need for gender-responsive, trauma-informed care within correctional facilities.

Trauma and Incarceration

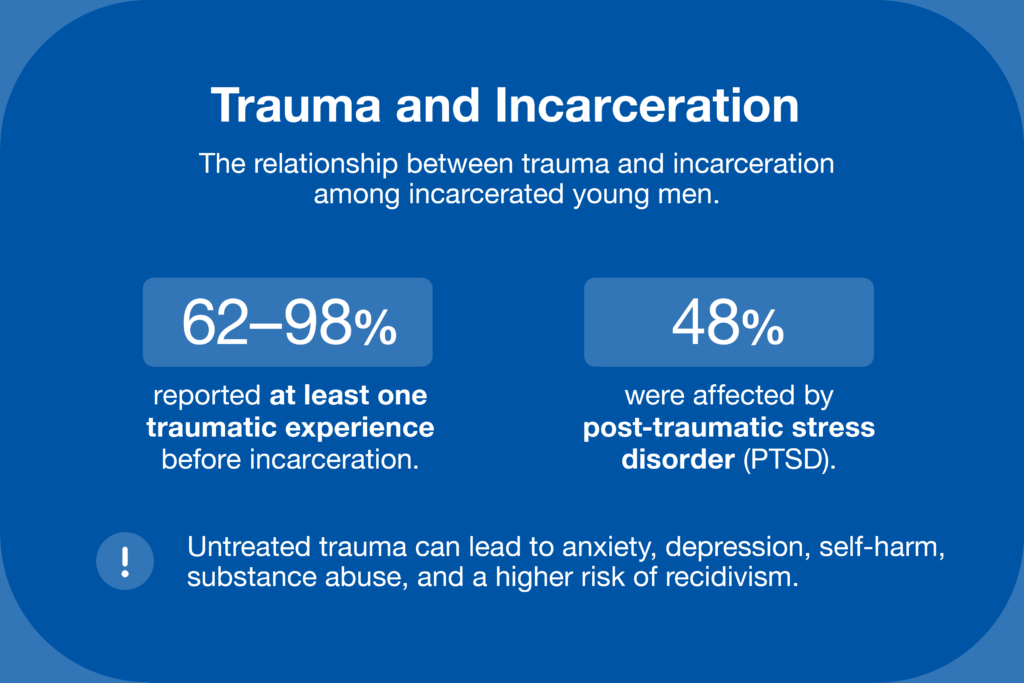

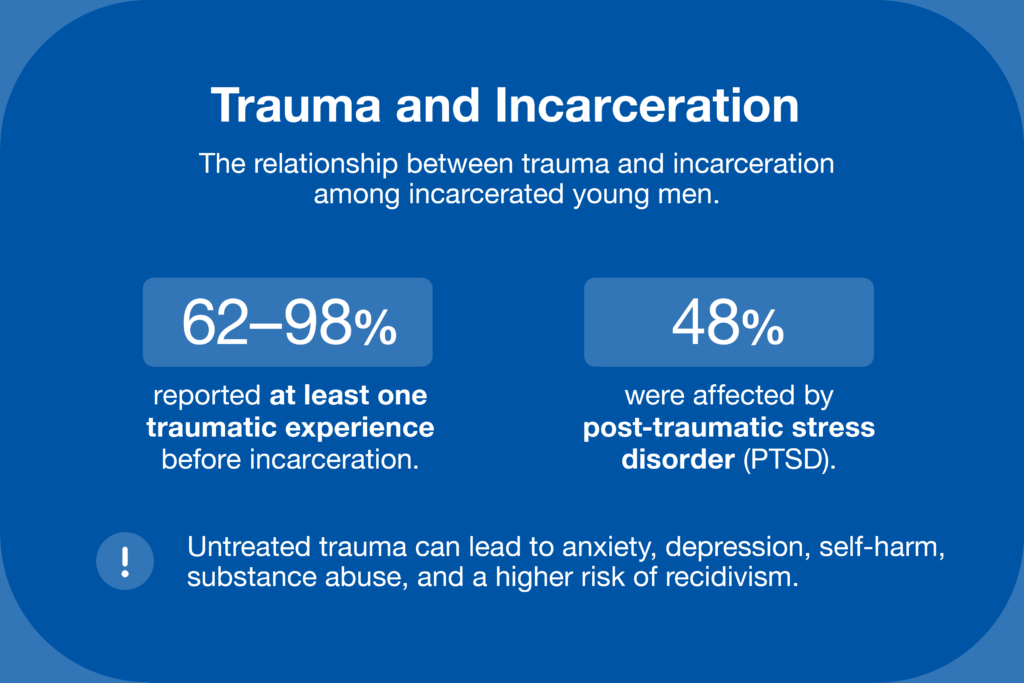

Many of the incarcerated young men in this study had already endured multiple traumas and losses before entering prison. Trauma was a common thread among participants, with rates ranging from 62% to 98% reporting at least one traumatic experience before incarceration. This is a strikingly high prevalence of trauma among incarcerated populations.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was also prevalent, affecting as many as 48% of the participants. The consequences of untreated trauma can be dire, leading to anxiety, depression, self-harm, substance abuse, and a higher risk of recidivism. Recognizing the impact of trauma on incarcerated individuals is essential for improving mental health outcomes and reducing reoffending rates.

The Role of Masculinity in Prison

Masculinity plays a significant role in the prison environment. The concept of "hegemonic masculinity," characterized by dominance, violence, and emotional restraint, prevails in many correctional facilities. Young men often use violence as a means to establish their identity as adults and men, and this behavior is influenced by the prison setting.

Interestingly, trauma experiences can be linked to the performance of masculinity. Some individuals may adopt exaggerated masculine behaviors, such as physical dominance, to compensate for their perceived vulnerability. This highlights the complex interplay between trauma, masculinity, and the prison culture.

Discouraging Help-Seeking Behavior

One significant finding from the study is that prison masculinities often discourage help-seeking behavior among incarcerated young men. The need to project an image of toughness and resilience is paramount for survival in prison and earning respect among peers. Participants emphasized the importance of not showing weakness, both to other inmates and prison staff.

The Need for Gender-Responsive Trauma-Informed Care

The article argues that understanding the impact of masculinity on incarcerated men who have experienced trauma is crucial for providing effective trauma-informed care within prison settings. Trauma-informed care should be sensitive to the prevailing organizational culture and masculine ideals in prisons. It must prioritize privacy, confidentiality, and safety while also supporting the development of positive and alternate masculine identities.

Conclusion

Incarcerated young men often carry a heavy burden of trauma. The environment in prison can exacerbate their symptoms and hinder their recovery. Recognizing the influence of masculinity on their experiences is vital for creating gender-responsive trauma-informed care programs. By addressing trauma and challenging rigid notions of masculinity in the rehabilitation and support of incarcerated young men, society can work towards better mental health outcomes and reduced recidivism rates.