Looking back just over two decades, criminal justice suffered from a lack of proven methods for reducing recidivism for formerly incarcerated individuals (Andrews & Bonta, 2003). Today, it is almost unimaginable that the field ever operated without practice methods that were studied and empirically validated through rigorous science. Science-based methods for offender work have been propelled by multiple streams of interest, united by evidence-based practices (EBP). This article examines relational and technical factors examined in prior research linked to reducing recidivism and improving outcomes in corrections.

Evidence over Ideology

Corrections has taken a positive turn. Failure can no longer be excused with “but we’ve always done it that way.” We find optimism in offender program development being based on evidence rather than ideology. The Risk-Need-Responsivity model (RNR; Andrews, Bonta, & Hoge, 1990; Bonta & Andrews, 2007) is one such practice. RNR provided much-needed empirically-grounded and scientifically-confirmed outcomes.

There are many offenders’ treatment programs to choose from—all with empirical support—which are aimed at reducing recidivism for community safety. Some of the more well-known models include:

- EPICS (Effective Practices in Community Supervision; University of Cincinnati Correctional Institute);

- STARR (Staff Training Aimed at Reducing Re-arrest; Robinson et al., 2011) ;

- T4C (Thinking for a Change; Bush, Glick, Taxman & Guevera, 2011);

- STICS (Strategic Training Initiative in Community Supervision; Bonta et al., 2010); and

- The Carey Guides (Carey & Carter, 2019).

These approaches are based on the RNR framework and form a group of Evidence-Based Practices (EBP) in offender work (e.g., Andrews & Carvell, 1998; Bogue et al., 2004; Bonta & Andrews, 2007; Dowden & Andrews, 1999, 2000).

Technical and Relational Aspects

What matters for outcomes? Is it the specific treatments used which involve the technical aspects of our work, or is it the relational aspects and the interpersonal skills of staff as they try to provide these technical features? The quick answer is to remove the “or”—this is an issue that does not fit an either/or dichotomy. Outcomes are impacted on both technical and relational aspects.

Correctional research has often been conducted as though what the staff person does, beyond technical methods, does not matter. This conjures up the image of a lab technician, where success involves following the right steps and proper techniques before they push a button to complete the operation. Early work on evidence-based practices focused almost entirely on the technical procedures and methods, while the relationship was neglected.

Responsivity: The Neglected Principle

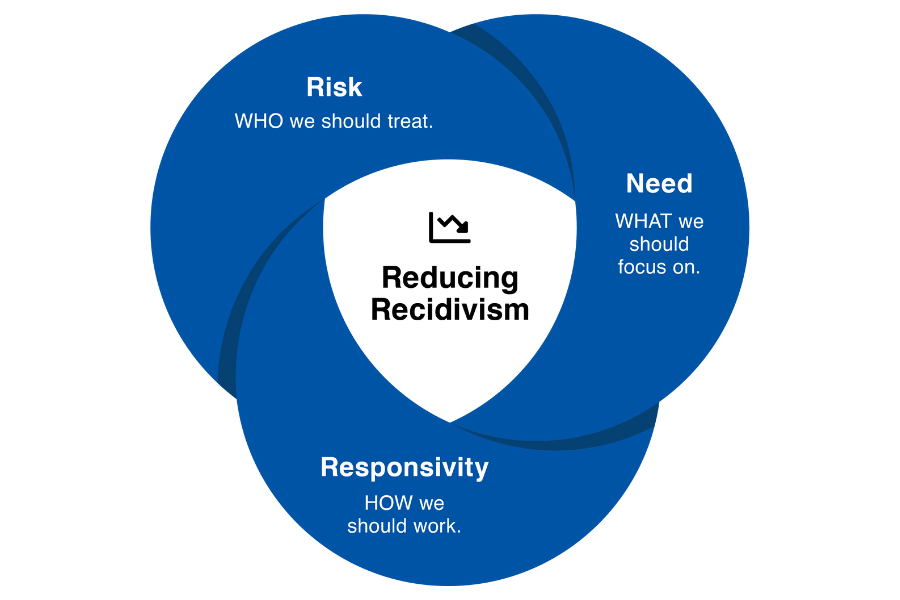

The RNR model offers a good example of early disregard for the working alliance (relational aspects) between officer and supervisee. The RNR model recommends that the level of service should match an offender’s risk of reoffending, that offender agencies should assess an offender’s criminogenic needs (i.e., dynamic risk factors) and focus treatment efforts on those issues. Further, this model proposes treatment should be matched to an offender’s learning style, strengths and abilities, and inherent motivation to assist positive behavior change. In simple terms, this model clarifies who we should treat (i.e., risk), what we should focus our treatment on (i.e., needs), and how we should treat those we work with (i.e., responsivity).

The RNR model offers a good example of early disregard for the working alliance (relational aspects) between officer and supervisee. The RNR model recommends that the level of service should match an offender’s risk of reoffending, that offender agencies should assess an offender’s criminogenic needs (i.e., dynamic risk factors) and focus treatment efforts on those issues. Further, this model proposes treatment should be matched to an offender’s learning style, strengths and abilities, and inherent motivation to assist positive behavior change. In simple terms, this model clarifies who we should treat (i.e., risk), what we should focus our treatment on (i.e., needs), and how we should treat those we work with (i.e., responsivity).

The responsivity principle suggests that programming should be tailored to the strengths, abilities, motivation, and the learning styles of individuals. Yet of RNR’s three core principles, it is responsivity that was relatively passed over, being labeled the “neglected R” (Duwe & Kim, 2018) and also called an “afterthought” (Taylor, 2016). RNR seemed to suffer from the famous George Orwell quote from his 1945 book Animal Farm, “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

Considering the important gains made with this model, it was encouraging that the model originators conceded their RNR approach was neither finished nor perfected. Even the model developers acknowledge the research into responsivity has been lacking—Bourgon & Bonta (2014) calling responsivity the “poor cousin” to risk and need. Don Andrews (2011) noted the “lack of evidence” regarding specific responsivity to be a weakness in the RNR approach. Duwe & Kim (2018) continue by warning that without a true focus on all three principles, fidelity can tumble, and outcomes can suffer.

To better explain responsivity, the RNR model breaks this principle into two categories:

- General responsivity and

- Specific responsivity.

Our interests lie in specific responsivity, for within this category is the focus on how staff respond at the individual level.

When the model was first launched, this category was focused on the offender, attentive to issues of offender motivation for treatment, gender, ethnicity, and race. However, more current investigations have expanded this principle to also look at provider characteristics, which has brought a focus to the officer-supervisee relationship.

Responsivity now considers what engenders high quality relationships, while it seeks to create an optimal learning environment with engagement and motivation. We have been so focused on the model and it’s techniques; we have overlooked the qualities of correctional staff—their relational behaviors that can improve outcomes regardless of the treatment method being used.

Following Allied Research to Increased Outcomes

Volumes of counseling and therapy research from the fields of psychology and social work have asserted the helping relationship’s positive influence on behavior change outcomes. These neighboring fields compiled over 1,000 research studies demonstrating that positive relationships are one of the strongest and most consistent predictors of outcomes across approaches (Orlinsky, Ronnestad & Willutzki, 2004). Holding fast to the idea that a strong working alliance was not appropriate to the field of corrections was an impediment that can no longer be tolerated. No matter what population you work with, the mechanisms that propel behavior change remain consistent. (Stinson & Clark, 2017).

Skeptics of the relationship’s influence need only consider the largest outcome study ever undertaken, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Project. This massive NIMH study found that improvement was only minimally related to the type of treatment received but was heavily determined by the client-rated quality of the relationship with the provider (Blatt, et al., 1996).

Now for the good news in corrections—the neglect that responsivity and the working alliance has suffered—is changing. Our field has moved from sole focus on compliance to one of compliance and behavior change (Clark, 2005). The valuing of engagement and motivation has sparked an expansion of specific responsivity to examine the officer-supervisee relationship (Skeem et al., 2007; Viglione, 2017; Grattet, et al., 2018).

One does not need a working alliance for compliance, but it is imperative if you seek behavior change.

Successful treatment and rehabilitation necessitate active acceptance and willing participation from the supervisee. To believe these conditions cannot be engendered with a corrections population is simply not true and now becomes an outdated belief held by those unable—or simply unwilling—to change how they work (Clark, 2020).

The Rise of the Dual-Role Relationship

The field of corrections is not alone in this disregard of relational factors and the helping alliance. A recent book from the Motivational Interviewing field (Miller & Moyers, 2021) reported that counseling, psychology, and social work have also focused primarily on the technical aspects of evidence-based treatments—neglecting or devaluing the relational skills of the counselors and staff themselves.

What has been an impediment to corrections has been the argument between punishment or rehabilitation. Law enforcement or social work. Hard or soft. Adding to this polarized debate is not our intent, for this dualism has grown stale. Research now points to a combination—or a best mix—of these opposing values.

What is recommended is a middle ground, which represents a “Goldilocks principle” of “just the right amount” of both control and a working alliance (Clark, 2020). This blend of control and connections has been found to be predictive of success on supervision (Lovins et al, 2018). Descriptions from research are plentiful:

- The “synthetic” officer—surveillance and rehabilitation to establish a “working alliance” (Devon & Polaschek, 2019; Viglione, 2017; Skeem & Manchak, 2008; Klockars, 1972 41).

- Firm, fair and caring–respectful, valuing of personal autonomy (Kennealy et al., 2012).

- “Hybrid” or “synthetic” approach to probation, combining a strong emphasis of

both social work and law enforcement. (Grattet, Nguyen, Bird and Goss, 2018). - Motivational communication strategies and Motivational Interviewing (Viglione, Rudes and Taxman, 2017).

- Open, warm, enthusiastic communication, mutual respect (Dowden & Andrews, 2004).

- Blending care with control through a “dual relationship” (Skeem, Lounden, Polsachek and Camp, 2007).

We do not discount the importance of technical aspects of evidence-based practices. Yet, in the follow up commentary (part II) coming in the next issue of the IACFP Bulletin, we will examine how evidence-based treatments cannot be separated from the correctional staff who deliver them. We will attempt to answer the critical question, “What are the essential relational behaviors correctional staff must be skilled in?” If the ingredients to improved outcomes involve both the technical and relational aspects, then look for “part II” of this commentary as we take a deeper look at the relational factors that can develop the all-important working alliance.

* References available upon request.

Michael D. Clark, MSW, is a former Executive Board member of the IACFP. He is the Director for the Michigan-based (USA), Center for Strength-Based Strategies, a technical assistance group that focuses on training Motivational Interviewing for substance use dependency/drug courts, corrections, juvenile justice, and child welfare.

Nancy L. James, MA, is a master’s level certified alcohol and drug counselor who has served as clinical director and a program manager for various in-patient and out-patient programs in Idaho, Missouri and Oregon (USA). Ms. James currently directs Cardinal Point-Oregon, an initiative developing exemplar substance use dependency treatment.