This practice commentary continues the first installment published in the October 2021 IACFP Bulletin. This two-part series was launched with an all-important question related to reducing recidivism:

“What matters for outcomes?”

A multitude of correctional research was reviewed, which has established that outcomes are impacted by both technical and relational aspects.

Technical aspects cover the treatment approach used (what you do), yet relational aspects cover the provider’s delivery of those treatment elements (how you do it). A frustration was shared that early work on evidence-based practices focused almost entirely on the technical procedures and methods, while the relationship between the supervising officer, counselor, or psychologist (provider) and the person-under-supervision (person) was neglected and/or misunderstood.

We asserted the argument between punishment or rehabilitation has been an impediment to corrections. The dualism of law enforcement or social work, hard or soft, coercive force or treatment has continued a polarized debate that has grown stale. Research now points to a combination—or best mix—of these opposing values. What is recommended is a middle ground, which represents a “Goldilocks principle” of “just the right amount” of both control and a working alliance (Clark, 2020).

Descriptions from research are plentiful: the “synthetic” officer – surveillance and rehabilitation to establish a “working alliance” (Devon & Polaschek, 2019; Viglione, 2017; Skeem & Manchak, 2008; Klockars, 1972); the “hybrid” approach to probation, combining a strong emphasis of both social work and law enforcement (Grattet, Nguyen, Bird & Goss, 2018); and blending care with control through a “dual relationship” (Skeem, Lounden, Polsachek & Camp, 2007). This initial commentary (October, 2021) closed with a pledge to review the provider effects and relational factors that impact the outcomes.

Provider Effects

The notion of “treatment” in the age-old correctional question, “Does treatment work?” was focused entirely on technical aspects. Why ignore providers, don’t they matter? Miller and Moyers (2021), who examined decades of psychological research—as it related to therapist effects—are very specific with their response to this question:

“There are important differences among therapists in their clients’ outcomes, for better or worse, and these differences have to do with interpersonal therapeutic skills” (p. 8).

Providers do matter, and these researchers took a deeper look to consider all of the other elements—that matter to outcomes—that might be found within a course of treatment. In treatment outcome research, such “other factors” include attributes of:

- The clients being treated (e.g., age, gender, problem severity, personality);

- The treatment itself (e.g., length, structure, procedure, methods, manual-guided, supervision, and quality assurance);

- The setting (e.g., residential or outpatient, correctional, faith-based, fee structure) and

- The providers themselves (e.g., education, experience, personality, interpersonal skills).

Miller and Moyers (2021) conclude, “studies of this kind typically find little or no outcome difference based on the specific treatments being compared, but a significant difference attributable to the therapists who provided the treatments” (p.10).

In light of these findings, we find it ironic that correctional research—dating back decades—would often mention relational aspects as after-thoughts or side notes. An example can be found in a meta-analysis which cited a reference from the late 1970s that recommended service providers “… relate to offenders in interpersonally warm, flexible and enthusiastic ways…” (Andrews, 1990, p. 376).

Individual Provider Effects

What about providers who are delivering the same treatment within an agency or facility? It’s not unusual for staff who work in corrections to make comparisons between individual providers regarding their ability to establish a working alliance. Is one provider better or worse than another? Are there individual differences? Miller and Moyers (2021) settle this quickly:

“The answer here is startlingly clear. There are often large differences among therapists who are offering the same or similar treatments, and those differences predict client outcomes and are consistent over time” (Krause et al., 2016; Owen et al., 2019).

Multiple studies within the fields of human services and corrections cite large differences between therapists and providers (Okiishi et al., 2003; Moyers, Houck et al., 2016; Welker et al., 2006; Clark, 2020b).

Relational Factors: Therapeutic Skills

The search for which therapeutic skills make a better provider has become a burgeoning topic of investigation in corrections (Clark, 2020a; Stinson & Clark, 2017; Lovins et al., 2018; Keannely, et.al., 2012; Bogue, et.al., 2008). William Miller, Ph.D., and Teresa Moyers, Ph.D., of the Motivational Interviewing approach have recently published the most complete accounting of therapeutic skills to date. In their 2021 book, “The Effective Psychotherapists: Clinical skills improve client outcomes” they posit eight relational skills—offering a working explanation while also reviewing the extant research for each skill. This list includes:

- Accurate empathy;

- Acceptance;

- Positive regard;

- Genuineness;

- Hope and expectation;

- Focus;

- Evoking; and

- Offering information and advice.

Space limits a thorough review of this list, but we offer an examination of the first two skills—all to set the stage for your own investigation.

Skill 1: Accurate Empathy

What it is: Empathy is the ability to feel with another person and understand what they are experiencing from their perspective. It is the ability to go outside of one’s own experience and see through the eyes, thoughts, emotions, spirit, and physicality of another. Approaching the client with curiosity, an openness, and interest to understand. It involves a deep listening to understand.

What it’s not: Sympathy, feeling sorry for someone. Assuming you know what the client believes without seeking their point of view. It is not feeling the exact same as the client or having had the same experience as what the client is undergoing. The opposite of empathy is asserting or imposing one’s own views, coupled with the assumption that the client’s views are mistaken or ill-advised.

Notes: You don’t have to have lived the same experience as the client. From the start, you know you don’t understand another person’s life but you want to understand. Empathy left as an internal feeling (within the provider) is of little use. It contributes to forming a partnership and empowers treatment when it’s communicated. The skill is found in working to understand and then connecting with the person to act as a mirror. Many consider reflective listening the best way to communicate your understanding.

Skill 2: Acceptance

What it is: This skill is also called “nonjudgmental acceptance.” It is a belief that the client has inherent worth and deserves respect without earning it. This involves accepting the bad and the good; accepting the inconsistent as much as the consistent.

What it’s not: It is not agreeing with their views—but it’s also not judging them. It’s not condoning negative behavior—but it’s also not shaming or criticizing their actions. It’s not ordinary communication one has with colleagues, family, or friends—that type of interaction can often involve arguing, criticizing, warning, moralizing, and labeling.

Notes: So many people under supervision have engaged in monstrous behavior.

The therapeutic skill of acceptance asks a personal question of each practitioner: “Has the person lost part of their humanity due to engaging in this hurtful behavior?” The spirit of acceptance says they have not—yet—it’s a question everyone must answer for themselves.

Miller and Moyers (2021) point out that communicating acceptance makes change possible—creating a climate where it’s safer to consider what is potentially threatening or difficult, while at the same time it diminishes defensiveness. The relational element of acceptance, as an attitude and behavior, runs contrary to a belief that people will change if they can just make them feel bad enough about themselves. These authors state, “Like punishment, a sense of unacceptability may suppress behavior, but it does not foster a new way of being. Paradoxically, it is when people experience unconditional acceptance of themselves as they are…that they are enabled to change.”

Discussion & Recommendations

First, consider that a large part of past correctional research has devalued relational factors. Misguided assertions such as “empathy doesn’t lower recidivism” abound. Yet, these skills which enable a quality alliance were never intended to lower recidivism in isolation. This is akin to expecting “just the tires” or “only the engine” to make an automobile functional. Relational skills are what researchers have called “necessary but insufficient”—necessary for lowering recidivism, but insufficient in and of themselves. If you use these relational skills with proficiency, you will still need technical treatment strategies to realize the change you hope for. Yet without these skills, the difficulty increases for goal attainment while the odds decrease.

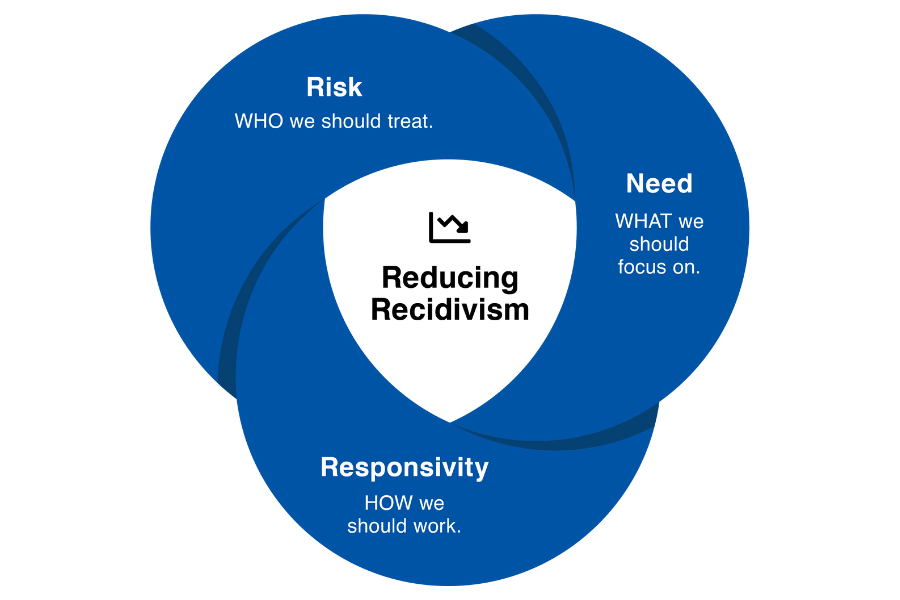

Helpful technical skills (what you do), coupled with effective relational skills (how you do it), must be placed in concert with client factors (who you’re working with) to empower outcomes (Clark, 2002). Consider the research for the effectiveness of the two relational skills reviewed in this commentary: accurate empathy and acceptance. Considering accurate empathy, Miller and Moyers (2021) state, “Of all the therapeutic factors that have been studied, accurate empathy has the most consistent relationship to positive client outcome” (p.28).

Regarding acceptance, these researchers note there is ample evidence that clients whose providers manifest and communicate acceptance generally have better outcomes. Miller and Moyers (2021) summarize the research on acceptance in this way:

“This is just one attribute of counselors, that by itself is modest in effect, but in combination with others can contribute to the large differences often observed in practitioner outcomes, even when allegedly using the same treatment techniques” (p.42).

Second, this call for high-quality relationships that are “dual, synthetic or hybrid” raises a “good news” / “bad news” contrast. The good news is that multiple studies find the quality of the provider-person relationship predicts success on supervision and determines whether programs actually reduce new crimes (Keannealy et al., 2012; Lovins et al., 2018). The bad news is that a group of researchers (Paparozzi & Guy, 2018; Skeem et al., 2017; Kennealy et al., 2012) worry about the difficulty that providers will encounter in balancing what they know (e.g., enforcement, supervision) with that with which they’re less familiar (e.g., relational factors, alliance-building).

Third, considering this “bad news” contrast, this commentary ends with a recommendation to consider the approach of Motivational Interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Central to Motivational Interviewing (MI) is the teaching of relational skills and the development of those direct practice competences. Know that MI has been called a “natural fit” for corrections (Iarussi & Power, 2018). Certainly one reason for this label is how MI offers the “how to’s” for negotiating this blending of control with a working alliance.

This recommendation is also made with consideration of staff. One reason for this label of “natural fit” is how the use of relational skills are employed to increase the readiness to change through a non-adversarial, non-punitive approach. Softer or smarter? MI has been called an “effective tool” for use within compressed time frames (Forman & Moyers, 2019). Providers, burdened by high caseloads, would ask, “Can you do Motivational Interviewing in five minutes?” We have answered this question with a rebound, “Can you ruin motivation in 5 minutes?” Of course you can. Little time to intervene means little room for error.

Training in MI can improve the likelihood that short interactions will prove helpful. You can become vulnerable to a paradox where you confront a person only to realize arguments or excuses, or you can use a guiding style to move more efficiently to productive conversations. Miller and Rollnick (2013) were the first to position this idea:

“Perhaps the underlying question is whether it is possible to make a difference with a few minutes of MI. Not only is it possible, but if you have only a few minutes to discuss behavior change, MI is likely to be more effective than finger-wagging warnings” (p. 343).

Finally, this recommendation considers our experience of correctional administrators. There are probation/parole/reentry chief and facility administrators across the 50 states (USA)1 which have seen the need to import the relational skills training found within MI. Some of the best content experts to teach relational skills have emerged from the MI training community2. An important point to remember is that a majority of these relational skills are not already present within a provider. These skills are much more complex than “being nice” or “making friends.” Rather, they form a multitude and range of professional skills to be learned and practiced.

To know that adopting an accepting style will diminish defensiveness is notable. Realizing that engagement with a supervisee is a critical first step, executives and researchers alike have found that MI can transform mechanical and depersonalized offender models by adding important relational counseling skills. These methods are available and within reach for providers who seek to learn the intricacies of establishing a strong quality alliance.

* References available upon request.

Footnotes:

1 Training has also occurred in 56 countries across Canada, South America, Europe, Africa, and Eurasia.

2 The main authorities for this approach can be found within the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT), which is an international organization established in 1997 as a professional community of practitioners and trainers (see Tobutt, 2010).

Michael D. Clark, MSW is a former Executive Board member of the IACFP. He is the Director for the Michigan-based (USA), Center for Strength-Based Strategies, a technical assistance group that focuses on training Motivational Interviewing for substance use dependency/drug courts, corrections, juvenile justice, and child welfare.

Nancy L. James, MA is a master’s level certified alcohol and drug counselor who has served as clinical director and a program manager for various in-patient and out-patient programs in Idaho, Missouri and Oregon (USA). Ms. James currently directs Cardinal Point-Oregon, an initiative developing exemplar substance use dependency treatment.