There exists a population of staff working in the corrections system who all manage common responsibilities, services, goals and participant demographics. These individuals, whom I have titled “Frontline Community Reintegration Officers” (FCRO), facilitate previous offender’s re-entry into the community outside of a correction, or prison facility.

FCROs are an international workforce, operating in various countries including Canada, the USA, and Australia, despite utilising different role descriptors (e.g., forensic case manager, parole officer, community corrections worker). Staff falling into this category have received lesser research attention comparative to well-defined forensic groups, such as prison staff and the police force.

When an extensive literature review was conducted, findings showed that much of the available research was outdated or focused on concepts only indirectly targeting staff wellbeing, such as staff productivity and burnout. Furthermore, when investigating which factors were more relevant and were experienced to be more adverse by FCROs, few studies took a ground-up approach by directly asking FCROs about their coping and stressors.

Despite this, it is evident that FCROs experience challenges, adversity and negative outcomes associated with low wellbeing, such as depressive symptomatology. Other forensic workforces, such as prison officers, experience these same outcomes and have been shown to have distinct factors of perceived workplace adversity and a variety of coping strategies that are associated with low psychological wellbeing and negative workplace outcomes. In contrast, the breadth and specificity of which factors are causing such outcomes for FCROs, and in which ways they cope, remains largely undefined in previous literature. As a result, a qualitative study was designed to:

- Gain contemporary information on the workplace adversity factors for FCROs;

- Understand the coping strategies used by FCROs;

- Extend upon previous research through rich qualitative data generated exclusively by the population of interest; and

- Create a basis of understanding from which evidence-based measures and interventions can be generated, specific to this population.

The design incorporated 6 focus groups consisting of 29 FCROs. Thorough transcriptions were taken and subjected to thematic analysis using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six step process for rigorous analysis.

Perceived Workplace Adversity

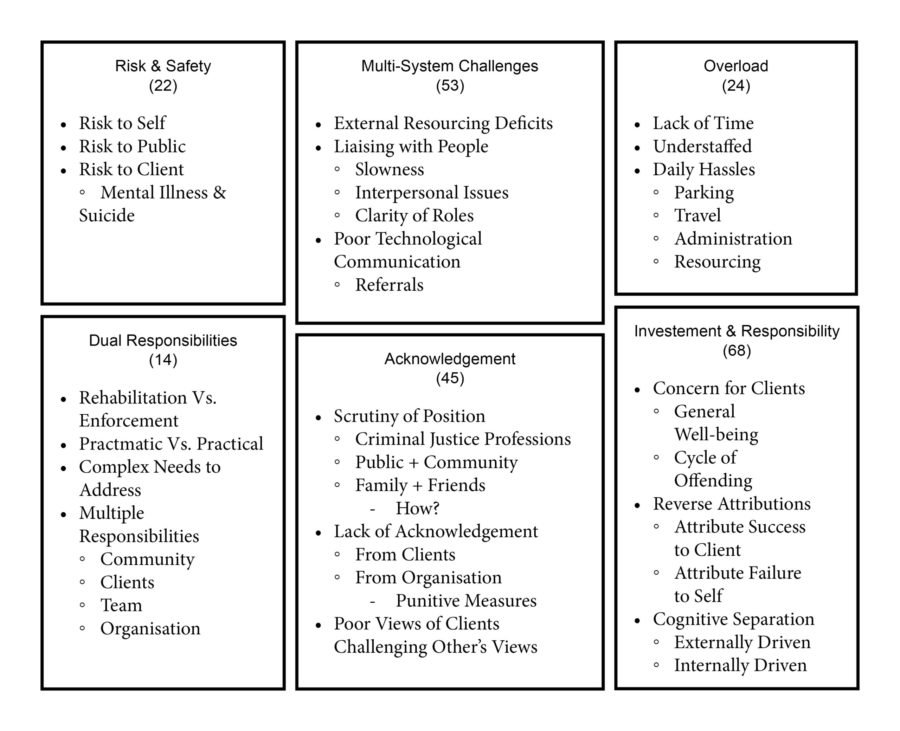

Participants were given several prompt questions to respond to in the focus groups regarding their perceptions of FCROs’ regular workplace adversity, including that which may differ from any general workforce experiences. The final thematic map regarding FCROs’ perceptions of workplace adversity is presented below in Figure 1 detailing six extracted themes with related sub-themes.

Figure 1. Final Thematic Map of Perceived Workplace Adversity for FCROs

Note. (22) = the relevant code was identified 22 times in the data.

The above six themes extracted from the data present the main sources of perceived adversity for FCROs. The findings contrast and extend upon a great proportion of literature related to FCROs’ adversity, as many of the prevalent themes were relatively minor within existing literature. For example, “Investment and Responsibility” has seldom been discussed in previous research, and often disregarded as lesser to organisationally based stressors. Furthermore, “Overload” from too much work and daily hassles is quite a common measure of workplace adversity and a commonly discussed theme in literature focused on subsections of the FCRO population.

However, the current data revealed a novel perspective, that overload was seemingly only caused by dealing with a variety of draining adversities in the workplace, that then resulted in hassles, such as finding a car park creating “tipping point” of overload. This may suggest that such hassles would not cause adversity if the work was otherwise safe and manageable. This misalignment with previous research suggests a need for greater consideration of validity when assessing and implementing resources targeting FCROs’ psychological wellbeing.

Coping Strategies

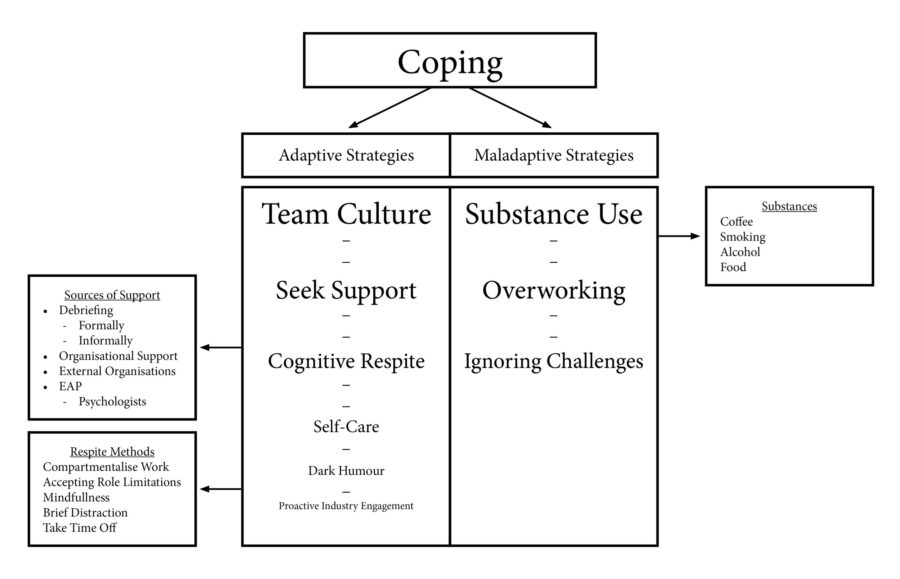

Throughout the focus groups, enough data was ascertained in order to establish the participants’ perceptions of the coping strategies used by FCROs to counter the adversity they face. Participants were encouraged to think of both adaptive and maladaptive strategies they perceive to be used among the workforce. The final thematic map for the focus group discussions regarding coping is presented below in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Final Thematic Map for Focus Groups Discussions on Coping.

Figure 2 displays the coping strategies that participants reported FCROs using to manage their workplace adversity. Several of these strategies—including seeking support, taking time off work and setting boundaries—were consistent with previous research. Many coping strategies from previous literature, which mainly focused on high-performing and effectively coping samples of staff, were not present in the current findings based on participants who were not selected on such criteria. Furthermore, many reported strategies were novel findings for this population. These discrepancies in findings between the two samples provides a foundation for investigating whether some strategies are responsible for differences in coping and achieving a state of wellbeing. Additionally, these findings provide a current perspective into how FCROs are managing adversity in their workplace.

Notably, there were several fewer maladaptive strategies comparative to adaptive strategies. Whether this is a valid indication of the use of fewer maladaptive coping strategies or merely a form of self or group preservation bias, is unknown. Overall, these coping strategies were all reflective of those documented in similar forensic populations. However, whilst the theme “dark humour” was discussed as an adaptive strategy, staff also noted it could be an indicator that someone isn’t coping. This warrants further investigation as to how exactly such a strategy is used and its implications for FCRO wellbeing.

Key Participant Quotes:

“You turn your phone back on, and you can have 30 messages from one client who has blitzed you the whole evening.”

“People do this profession because they care.”

“We are on eggshells.”

“There are limitations to what we can do because of the pressure and demand for the services that we are linking people to.”

The current study presents theoretical, methodological and practical implications. The exploratory, qualitative design enabled in-depth resources for furthering the understanding of FCROs’ workplace adversity and coping strategies. By using the personal experience of the staff themselves, this has positioned future literature to build upon research and interventions with FCROs’ beneficence and lived experiences at their core. This is an addition to previous literature which has largely focused on staff who are coping well and succeeding.

Furthermore, multiple stakeholders can draw value from the current findings. The organisation who employs the sample used in this study can use the information to inform the development of policy, as well as interventions targeted at improving and minimising coping and adversity, respectively. Regarding staff individually, recommendations can be made to directly address their stressors and related coping strategies. Since peer debriefing was identified as an adaptive strategy, FCROs could seek to maximise its use. Their daily work routines, such as driving or working in different locations, presents opportunities for peer debriefing via car-pooling or encrypted messaging software to ensure debriefing occurs despite time or place constrictions. Future research in this area can extend the utility of these findings by generating a validated measure of adversity for FCROs and generating evidence-based interventions.

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend my thanks and acknowledgement to the International Association for Correctional and Forensic Psychology for awarding me a research scholarship in order to assist me in my academic and research endeavours, making such a study possible. Furthermore, thank you to the frontline community corrections staff and my research supervisor who gave me their time, assistance and insight.

About the Author

Teagan Connop-Galer has studied a Bachelor of Psychology (Honours) at Swinburne University of Technology in Australia and graduated with First Class Honours in 2019.

Teagan Connop-Galer has studied a Bachelor of Psychology (Honours) at Swinburne University of Technology in Australia and graduated with First Class Honours in 2019.