Previous issues of the IACFP Bulletin included a summary of recent research examining the relationship between solitary confinement of adults and mental illness in corrections and the improvements in policy and treatment that have taken place in the Oregon Department of Corrections. In the article summarizing recent research, readers were invited to answer four questions about their experiences, from the perspective of practitioners. Those questions were:

- Have you changed your policy on placing incarcerated persons in isolation cells over the last five years?

- Are you aware of criminal justice systems that have either not allowed mentally ill persons to be placed in isolation cells or that place an upper limit on their time in this type of confinement?

- As a practitioner, how do you assess an incarcerated person’s functional impairment? How do you communicate that to security staff?

- What interventions do you utilize to reduce behaviors associated with mental illness as an alternative to past utilization of isolation cells?

The responses we received highlighted three jurisdictions that have policies and practices that practitioners should know more about if they want to make improvements in the treatment of the mentally ill in secure settings. This issue will highlight the changes that have taken place in Canada and, more specifically, the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC). This article is based on an interview with Dr. Anne Connell, Forensic Psychologist and Advisor to the CSC Assistant Commissioner, Health Services, with supporting documentation provided by Dr. Connell, and information available on the internet.

CSC History

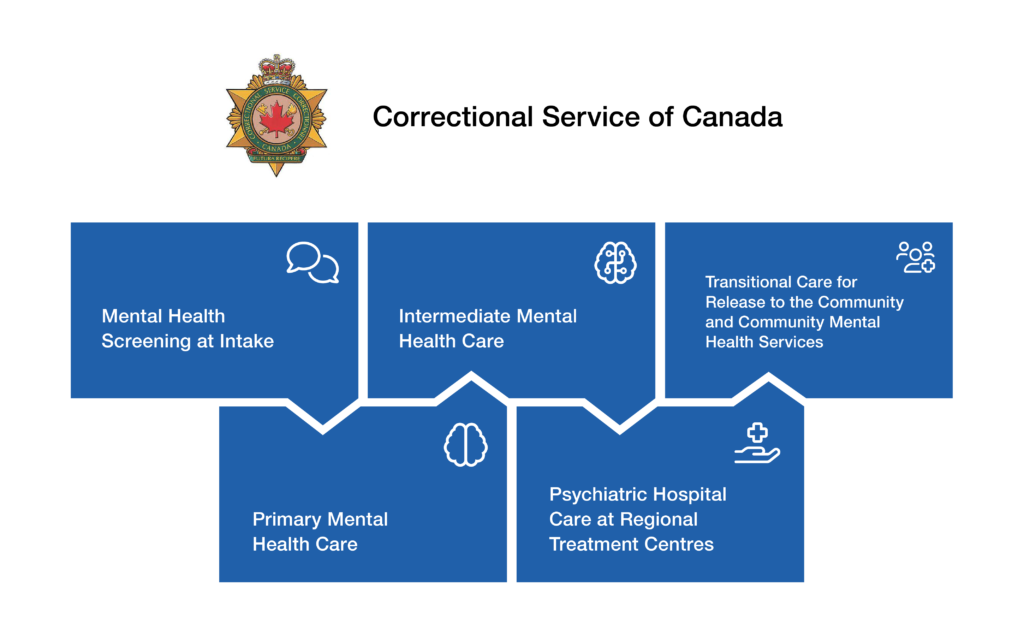

The Correctional Service of Canada’s Mental Health Strategy is founded on five key components, falling along a continuum of care from intake through to end of sentence. The components are: (1) Mental Health Screening at Intake; (2) Primary Mental Health Care; (3) Intermediate Mental Health Care; (4) Psychiatric Hospital Care at Regional Treatment Centres; and (5) Transitional Care for Release to the Community and Community Mental Health Services.

New legislation enacted in 2019 included fundamental and transformative changes related to Health Services and the working relationship between health staff and operational staff. These changes, aimed to enhance health services across CSC, are supported by the legislation, regulations, and significant funding. This funding is enhancing health service delivery in both primary care and acute levels of care, as well as providing additional resources to assist in the diagnosis of mental illness for offenders at intake. Importantly, the investments provide for over $9M in funding for psychiatry, which will be indexed to changes in population size over time. Of this, approximately $6M will go to increased resources at Regional Treatment Centres and $3M to regular institutions to strengthen assessments at intake, and the provision of treatment through primary and intermediate mental health care.

The resource indicator for psychiatry was established using CSC prevalence data and benchmarking with the American Psychiatric Association Standards for Psychiatric Services and other correctional jurisdictions. Psychiatric assessment and diagnosis at time of intake enables early detection of mental illness and assists in determining the appropriate pathway of care (by matching level of mental health need with appropriate service intensity and security level) and prioritization of inmates for services. Enhancement at intake will enable inmates with moderate to severe impairment to be admitted directly to health care units, such as Regional Treatment Centres or Intermediate Mental Health Care Units. In addition, the funding will support the establishment of professional practice structures in each region that are critical to supporting high quality care.

Also as part of the legislative changes, administrative segregation was eliminated at CSC and a new correctional model was adopted. The new correctional model included the establishment of Structured Intervention Units (SIUs) to provide an alternative institutional living environment when an inmate cannot be maintained in a mainstream inmate population, pursuant to legislation.

Other key features of the new legislation and correctional model include:

- Introduction of Independent External Decision Makers (IEDM) to ensure oversight and transparency;

- Legislative requirements for mental health assessments;

- Quality of Care reviews;

- Introduction of processes to support CSC’s efforts to address the health needs of individuals in SIUs;

- Strengthening health care governance by affirming CSC’s responsibility to support health care professionals in maintaining their professional autonomy and clinical independence; and

- Providing for patient advocacy services in designated penitentiaries to help inmates understand their health care rights and responsibilities.

Structured Intervention Units (SIUs)

SIUs are stand-alone units within an area of a CSC penitentiary. They are used when inmates cannot be managed safely within a mainstream inmate population for security reasons, for their own safety, or when needed during an investigation. While SIUs are not a mental health strategy, there are mental health protocols and services associated with the model. In SIUs, inmates receive targeted interventions, programs, and health care – including mental health care – with the goal of returning to a mainstream inmate population as soon as possible. SIUs provide inmates with the following:

- Targeted interventions and programming tailored to address their specific and unique risks and needs;

- Opportunity to be outside their cell for at least four hours a day;

- Opportunity to interact meaningfully with others for at least two hours a day; and

- Daily visits from healthcare professionals, who may recommend for health reasons that the inmate’s conditions of confinement be altered or that they not remain in the unit.

To ensure inmates in an SIU maintain continuity with their Correctional Plan, they are provided opportunities to continue or commence programming, interventions, and services. The goal of the interventions is to provide offenders with the tools needed to get back into a mainstream population as soon as possible. Providing opportunities for meaningful human contact through the provision of programs, interventions, services, cultural activities, religious and spiritual practice, leisure activities, and family or community contact is considered essential in supporting an inmate’s return to a mainstream inmate population at the earliest possible time, while maintaining continuity in meeting the objectives of their Correctional Plan.

Mental Health Services in SIUs

Health professionals work collaboratively with the Interdisciplinary team to address the health needs of individuals who are in an SIU. It must be ensured that all individuals authorized for transfer to an SIU have an identified Most Responsible Provider (MRP). For continuity of care, individuals in the SIU will continue to receive health services at the appropriate level of care in accordance with any existing treatment plans and the National Essential Health Services Framework.

Health assessment, including mental health, is required within 24 hours of transfer to the SIU and every 14 days thereafter. A more in-depth mental health assessment is completed within 28 days of transfer to the SIU.

The purpose of the first day health assessment is to assess the individual’s current health, including mental health, to determine if follow up is required and to consider the appropriateness of immediate referral for a further assessment in a timeframe that reflects the level of need.

Following this, individuals are visited daily by a registered health care professional to conduct a wellness assessment to identify the emergence of physical and mental health symptoms for individuals who do not have identified pre-existing health needs and allow appropriate clinical monitoring and continuity of care for those who have identified pre-existing health needs. The health care professional must observe and speak directly to the individual, arrange further assessment if required, and try to assess more than once if the individual does not consent to participate in the assessment process.

The more comprehensive mental health assessment provides an understanding of the individual’s emotional, cognitive, and behavioral functioning. These assessments include completion of the Mental Health Needs Scale, which assists mental health professionals in determining the level of need and associated level of service.

A registered health care professional may, for health reasons, recommend to the Institutional Head that the conditions of confinement of an offender in an SIU be altered or that the inmate not remain in the unit. As reported for the Oregon Department of Corrections in a previous issue, this may include more contact or out of cell time, release, or other accommodations to support the treatment plan. If the Institutional Head does not agree with the health care professional’s recommendation, they must provide a rationale and seek review by a higher authority in headquarters that includes health care in the decision-making. The Health Committee, chaired by the Assistant Commissioner of Health Services, will review the inmate’s case, and if the health care recommendation is again not implemented, an IEDM will review the case and make a decision. IEDMs are appointed by the Minister of Public Safety to provide external oversight of decisions to maintain inmates in SIUs, as well as their conditions of confinement.

Moving Forward

Current initiatives underway include further integration of the health care system with a focus on early diagnosis and treatment through the implementation of the Person Health Care Home (PHCH) Model and the development of guidelines for the treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder in the correctional context.

The PHCH is a new patient-centred model of care, which will contribute to better integration and person-centred care for inmates. The model focuses on integrating all health care services across primary care, mental health, public health, community and social supports, wellness, and supportive living. In addition the model allows consideration of a patient’s social determinants of health (e.g., early childhood development, educational development, social connectedness). Through this model, the recipient of care plays a key role, has a say in the services they are receiving, and is included in planning for their care and decision-making.

The PCHC Model solicits the involvement of the person receiving care (along with a support person/family/system where applicable), and that of interdisciplinary health services, to develop an interdisciplinary Integrated Care Plan (ICP). The ICP identifies the MRP and what role each discipline has (based on their assessments) in helping the patient achieve their identified health goals. PHCH is crucial in providing care for patients experiencing multi-morbidity. This initiative will address a need for standardized, evidence-based, interdisciplinary care management plans that identify appropriate assessment tools, clinical interventions, intensity of treatment, timeframes, and outcomes for comparable patient groups.

The Borderline Personality Disorder Treatment Guidelines will propose a consistent and comprehensive approach to identifying, treating, and managing offenders with Borderline Personality Disorder, including those with comorbidities, to establish practices that are practical and informed by research. To complement CSC’s Suicide Prevention and Intervention Strategy, the Borderline Personality Guidelines will address assessment and interventions for self-injury in those with Borderline Personality Disorder. Principles of Trauma Informed Care and Client Centred Care are a major component of the Borderline Personality Disorder Treatment Guidelines. The Borderline Personality Disorder Treatment Guidelines and Person Health Care Home projects will provide a consistent approach to comprehensive assessment, case formulation, interventions and outcome measures for complex cases.

Summary

CSC has engaged in an intentional effort to improve conditions overall and specifically for those individuals with mental health issues who may struggle in mainstream populations. The implementation of a PHCH Model will allow them to not only maintain organizational standards of care, but also professional standards and ethics and community care standards.

Though they acknowledge there is more to do, CSC’s incremental journey to improve through the adoption of a new correctional and health services model is a worthwhile example for others.

* References available upon request.

Cherie Townsend is the IACFP Executive Director. She also works as an executive coach and consultant. Ms. Townsend previously worked as a leader and practitioner in juvenile justice systems for nearly 40 years.