The recently published study “An updated evidence synthesis on the Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) model: Umbrella review and commentary” by Seena Fazel, Connie Hurton, Matthias Burghart, Matt DeLisi, and Rongqin Yu — summarized within this issue of the IACFP Bulletin — takes a critical look at the RNR model, which has become a widely accepted model for managing justice involved individuals in both custody and community correctional settings throughout the world. Due to the findings expressed by the researchers, IACFP received several inquiries asking for guidance regarding the article’s content. The approach we have taken is three-fold:

- Summarize the article and its main points.

- Ask a group of experts to respond directly to the research and conclusions of the authors.

- Provide a supplementary article on model pluralism that is reprinted, with permission, from Justice Trends magazine and the author.

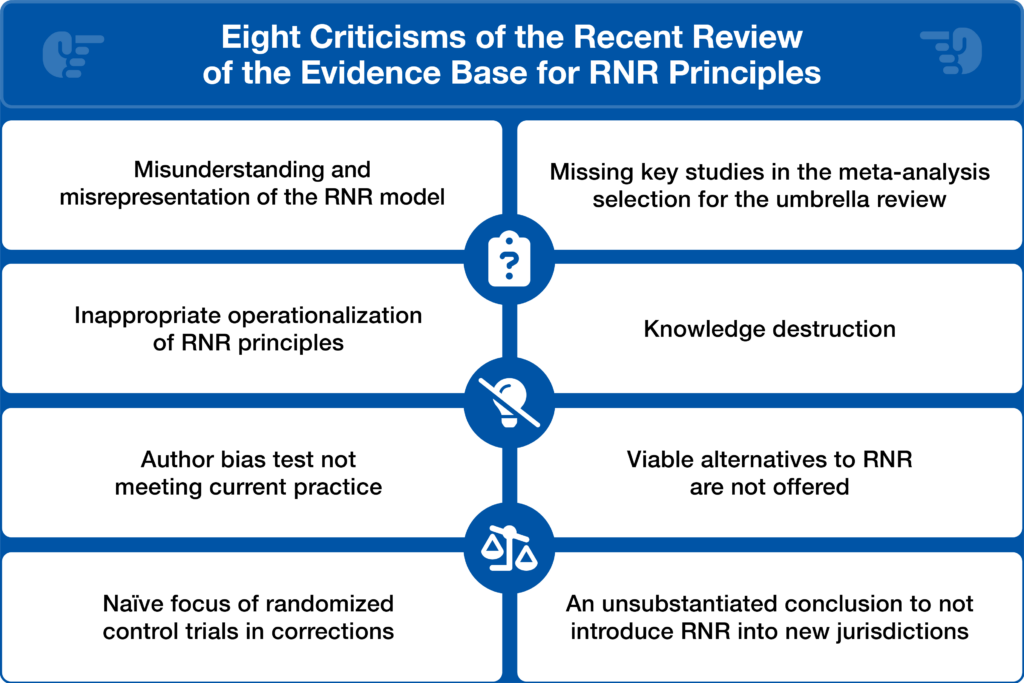

The perspectives from Jim Bonta (Canada), Joel Dvoskin (USA), Paul Gendreau (Canada), Mark Olver (Canada), Devon Polaschek (New Zealand), and Frank Porporino (Canada) were articulated through an informal group conversation, with highlights from that conversation shared below. Several of these individuals intend to offer a more formal response via an academic publication. The group identified the following common issues and unique considerations:

- Misunderstanding and misrepresentation of the RNR model

- Inappropriate operationalization of RNR principle

- Author bias test not meeting current practice

- Naïve focus of randomized control trials in corrections

- Missing key studies in the meta-analysis selection for the umbrella review

- An unsubstantiated conclusion to not introduce RNR into new jurisdictions

- Viable alternatives to RNR are not offered

- Knowledge destruction

We appreciate them taking the time to offer their thoughts based on their experience with RNR and with the issues raised in the summarized article. We share their questions, insight, and criticisms here so that our readers may gain a more complete understanding of RNR as well as the model’s strengths and weaknesses from a research perspective. For practitioners, this series of responses offers thoughts about how they might best meet the needs of the individuals they work with.

After reading “An updated evidence synthesis on the Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) model: Umbrella review and commentary,” Jim Bonta offered these direct rebuttals:

- “You mistakenly identify the Central Eight as the basis to fourth-generation risk assessment. Alas, this forms the basis to third generation (p. 1).

- I am not sure how closely you read the RNR model. You cannot evaluate the risk principle by simply looking at outcomes for low- and high-risk clients who attend treatment. You need to also know the intensity of treatment and if it is matched to client risk.

- Your interpretation of the need principle is completely wrong. On page 2 you write: “For need, studies were included if they assessed the predictive accuracy (italics added) of one or more risk assessment tools for recidivism outcomes or if a study directly assessed a treatment program reflecting the need principle.” The predictive accuracy of criminogenic needs is important, but it does not form a test of the need principle. We must assess if the treatment targets criminogenic needs, and if successful targeting of criminogenic needs is associated with reduced recidivism. Calculated AUCs are a predictive accuracy statistic, not a measure of the effects of treatment. There are plenty of meta-analyses on the predictive accuracy of the Central Eight and this review adds nothing to them. Finally, with respect to specific responsivity: Why is treatment completion an outcome measure? This is confounded with risk. All in all, if RNR is not accurately conceptualized then everything that follows is meaningless.

- You engage in Knowledge Destruction (as described by Technical Note 10.1 of PCC 7th edition) by suggesting ambiguity and setting almost unattainable goals that no one study or review can achieve (i.e., covering all the principles, methodologies, and theoretical perspectives). As you write on page 2: “RNR is reported (emphasis mine) to have a broad existing literature base, including primary studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses across the principles. However, the evidence base is also quite dispersed, making it difficult to assess the model, particularly as many of the systematic reviews in the area present conflicting findings. Existing syntheses, such as Polaschek (2012); Ward, Melser, and Yates (2007); and Ogloff and Davis (2004), tend to focus either on a single principle or to cover the model only conceptually, with little methodological assessment or critique.” Can any review meet these standards?

- The ultimate knowledge destruction technique: “remind the readers that studies that report positively…are based upon the conclusions of the authors of the reports themselves.” You make a valiant effort to express that your motivation in excluding reports written by the RNR developers and their colleagues is based on science (the allegiance effect, p. 7). You could have at the very least identified what ‘authorship bias’ studies were excluded and maybe provide the effect size for them so the reader can compare (e.g., in Figure 2 you go from seven studies reported in the text to four studies in the figure). It is also noteworthy that only your work is described in Figure 4 and they are all prediction studies (where is Olver et al., 2014?).

- You complained, in part, that previous reviews focused on a single principle. And yet you did the same. Adherence to only one principle is a good first step but, as we have ‘reported’ on many occasions, adhering to two and three principles is even better.

- Your conclusion is truly astounding: ‘Without this [higher quality research], introducing RNR into new jurisdictions should not be recommended’ (p. 8). RNR has guided program development for decades and have positively impacted the lives of thousands of criminal justice-involved clients. Are we to discard all of this?”

Paul Gendreau will be co-authoring a formal response with Jim Bonta. His brief comments are:

“In the more formal expert group response, Jim and I will address author bias in one way by using the CPAI, which is a powerful tool to separate author bias from program therapeutic integrity (TI). This is done by scoring the method section and any other related information regarding a publication on a treatment programs effectiveness.

It is plausible that Jim’s and other Canadian-led RNR studies will have higher CPAI scores — maybe even higher than others not done by the Canadian school — because we will have information on what was exactly done with regards to TI (e.g. the classic Rideau prison study and Jim’s P/P studies). Note that Fazel displays no awareness of anything about TI, only about research design, which says little if anything about how well treatment is provided. He just resorts to cheap shots such as financial conflicts (p.7) and ultimate dismissals that RNR doesn’t work, redolent of the initial ad hominem primitive debates from the Martinson ‘nothing works’ era. In addition, there is a second way of demonstrating the validity of research findings, which is by way of replication. To this end, Jim and I have produced evidence of the RNR model being replicated by independent researchers.

Lastly, attention is drawn to the unfortunate fact that Fazel, et al do not report the results of RNR studies in a transparent manner that is easily understood by practitioners and policy makers, let alone by researchers. It has been demonstrated that the Fazel outcome measure, the ratio of two ratios, is incomprehensible to all but the mathematically inclined. Rather, the results fom the RNR studies are of a magnitude (in % terms) that are cost effective.”

Mark Olver comments further about the problems he identified in this manuscript after a brief review:

“At first glance, I have a number of concerns with the review. I saw missing key works, idiosyncratic interpretation and criteria for study methodology and findings, and overstated conclusions. I would also note that they offer no viable alternatives to RNR for correctional systems to administer, treat, manage, and reintegrate correctional populations. I'm not sure what else they would suggest.

As a case in point, our LSI meta-analysis published in 2014 in Psychological Assessment — containing almost 400 citations — didn't get picked up in this umbrella review, which is a notable omission (even if the study authors would have chosen to discount it since Steve Wormith was a co-author, which I would object to, as I was lead author and Steve did not insert any agenda or undue influence). Or even dozens of meta-analyses of other forensic/risk measures. Even if the findings, which are actually pretty decent, are taken at face value, the conclusion to not introduce RNR into new jurisdictions is unsubstantiated. I could be mistaken but I also don't believe anybody in the author team has a mental health or human service delivery background, such as forensic clinical psychology; this matters as training and practice in criminal justice and correctional psychology enables one to contextualize their interpretation of data, refine clinical research questions, and to draw practical conclusions on the applications of findings to correctional, criminal justice, and forensic settings. The interpretation of effect sizes seems to be selective (including an idiosyncratic metric for AUCs, what is their basis for low, medium, or high?), they overstate author bias, and seem to place too much weight on RTCs, which have poor external validity and, for ethical reasons, I would argue often cannot be done with correctional populations. It is hard to place much weight or confidence in the conclusions from this review. There are probably close to 1,000 replications of RNR in some form over the last 35 years from around the world.

In addition to considering model pluralism, I think there would be value in more formally rebutting the assertions of Fazel, et al backed by supporting data and sharpened operationalizations of RNR as we know it. This could be akin to the Good Lives Model (GLM) and RNR exchanges. The Fazel, et al paper is troublingly misleading and its conclusions — which appear to be based on an unrepresentative and partisan examination of a group of studies with inaccurate and oversimplified operationalizations of RNR — are irresponsible. A rebuttal to set the record straight and to identify errors, omissions, and caveats of this study by an expert RNR group is needed, particularly for the benefit of those who might be less well informed.”

Frank Porporino, responding to Mark, said:

“I agree completely with Mark’s observations regarding the Fazel, et al. paper…but I have to say that I disagree with the idea that there are no ‘viable alternatives’ to RNR. Though the Good Lives Model may not have the strong empirical grounding of RNR, Tony Ward has been one of the most insightful critics of some aspects of RNR…and his work on GLM is being increasingly respected and implemented. For example, I chaired a session at the last ICPA Conference where GLM was being used as the underlying framework in Belgium for developing the regime in what they refer to as ‘small detention houses.’ I really don’t see the point of pitting one paradigm against another…good evidence should be respected regardless of the particular paradigm it supports.

My own view is that we need ‘model pluralism.’ It’s a notion I developed for a keynote I gave to the 5th World Congress on Probation in 2022 and for a piece that the editors of Justice Trends magazine recently asked me to write on the state of Evidence-Based Practice. (Note: This article is also included in this edition of the IACFP Bulletin.)

Readers might also be interested in this new initiative from Ioan Durnescu in Romania (also well known in Europe for his Core Correctional Skills workshops). It’s what he calls ReHub, a digital app that features interviews with experts in the field. Shadd Maruna’s 50-some minute interview was perhaps the clearest and most compelling explanation of the desistance paradigm that I’ve ever heard.”

Joel Dvoskin responded:

“In my opinion, the idea that these models are competitors might have relevance to academia, but to offenders and the people who manage, serve, teach, and train them, the things that matter are tactics, strategies, interventions, and skills — in other words, the things we do and say to people. If an intervention is helpful to someone who is desisting from crime, who cares whether it emerged from one academic model or another, or both, or no particular model at all?

I have nothing against these models. I find much to admire about almost all of them. What offends me is the idea that they are in competition with each other.

Frank’s article on model pluralism is a thing of beauty. I enthusiastically support this concept and hope others will consider it thoughtfully.”

Devon Polaschek identified similar issues and focused on the authors’ interpretations:

“I doubt any expert in RNR was involved with the review process of this article.

In addition to the points made by Jim and Paul — particularly around NHST, odds ratios, etc. — and even whether this is really a legitimate umbrella review, I’d add that there are some disturbingly wonky conceptual angles too, though some of it is subtle.

Perhaps someone can tell me why I can’t make sense of how Fazel has operationalised the principles. For instance, ‘This aims to translate the risk principle into practice — that the risk level is judged according to criminogenic needs.’ (p. 1) This seems a rather simplistic and reductionist view of the need principle. And in the same paragraph: If ethnic minorities have higher dropout rates from a particular treatment programme, instead of adapting it to be more engaging for them, the take is that we should instead make the programme shorter, so it will end before they have dropped out?

Regarding studies that examine the need principle empirically Fazel wrote: ‘For need, studies were included if they assessed the predictive accuracy of one or more risk assessment tools for recidivism outcomes.’ So, he sees validating the predictive accuracy of a third-generation dynamic risk instrument as a test of the need principle, without indicating anything about whether treatment of CNs leads to better outcomes than otherwise? And how would the Static-99 or PCL-R AUCs be a test of the need principle when they are static-factor based?

All the way through his interpretation is just a bit ‘off’, indicating to me not just intentional knowledge destruction, but that he really doesn’t ‘get’ the model.

As for author ‘bias’ his approach here seems to be simply ad hominem. Other people test for author bias by comparing the ‘biased’ authors’ work with that of those deemed not to be biased. That way we could have an empirically-based discussion about bias.

Finally, the understanding he conveys of RCTs is, to say the least, naïve, given how difficult it is to meet many of the assumptions that make them superior in any setting where double blinding is not possible, where selective attrition and contamination across conditions can and does occur, failing to create equivalence, and given findings suggesting the results of existing RCTs are not necessarily too far from the much more numerous high-quality, quasi-experimental designs in offending-related intervention evaluations.

As far as overall social context is concerned, I’d be interested to see him present a series of figures like he has in this paper, showing as they do almost exclusively positive effects, to a cancer conference, and then to suggest that we stop implementing the treatment of said cancer until we ‘know more.’ That would immediately raise the important ‘compared to what?’’ question (i.e., what are the effects of returning to the status quo while we wait?).”