Dr. Orla Gallagher recently received her PhD from University College Dublin and she currently works as a Post-Doctoral Researcher within the Irish Prison Service, focusing on the role of experts by experience and how neurodiversity is responded to within the correctional system. In this article, she discusses the four studies that formed her doctoral thesis, Managing Serious Violence in The Irish Prison Service: Exploring the Experiences of Prisoners and Prison Officers through the Lens of the Power Threat Meaning Framework. Gallagher was a recipient of the 2023 IACFP Student Research Award.

In October 2017, I entered uncharted territory as the first PhD candidate to be funded by the Irish Prison Service (IPS), and was tasked with conducting a complete programme of research exploring serious violence in Irish prisons. Over the following six years, this research developed into four distinct studies with two core foci – the Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF) and the Violently Disruptive Prisoner (VDP) Policy. With my PhD now complete1, this article provides an overview of this research, and the implications it has had.

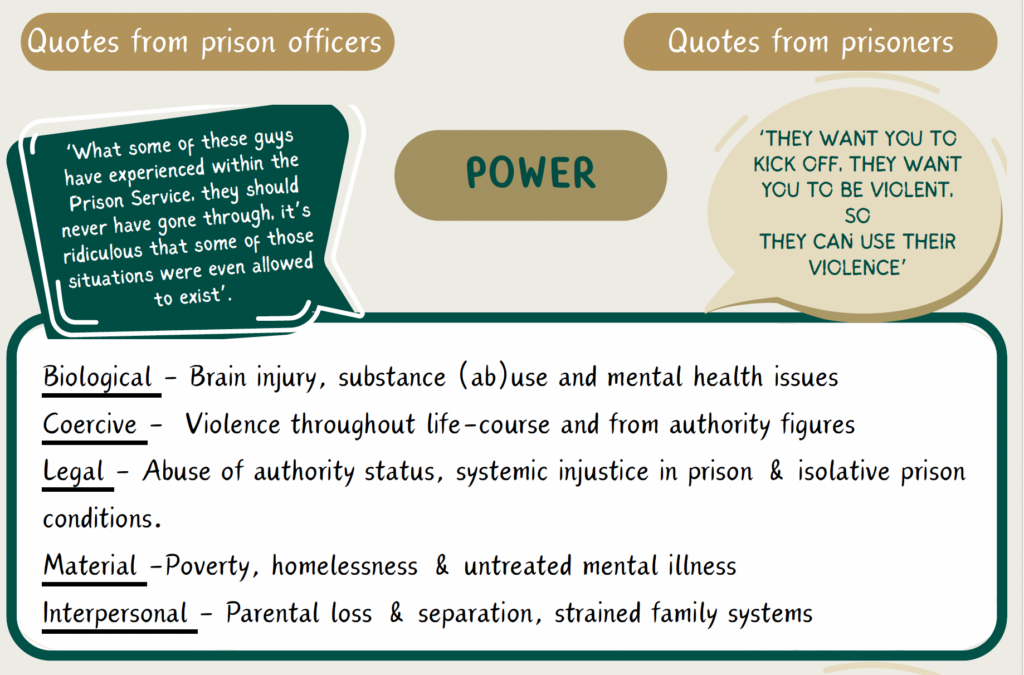

To begin, it’s important to position this research within the theoretical framework that has guided it. The PTMF was published by the British Psychological Society’s (BPS) Division of Clinical Psychology (DCP) in January 2018 and was lead-authored by Dr. Lucy Johnstone and Prof. Mary Boyle. The PTMF offers an alternative way of understanding the origins, experiences and expressions of emotional distress and troubled/troubling behaviour. The holistic structure of the PTMF lends itself to understanding a wide range of phenomena, including offending behaviour and violence, hence its applicability to this research. The PTMF contains four core components that can be translated into four core questions:

- Power – what has happened to you?

- Threat – how did it affect you?

- Meaning – what sense did you make of it?

- Threat response – what did you have to do to survive?

The PTMF also highlights the moderating role of various exacerbating and ameliorating factors throughout the power-threat-meaning-response process. The PTMF was published shortly after I commenced my PhD studies, and I saw this as a timely and compelling opportunity to “test” a new and novel way of understanding violence. Thus, as my research progressed, the PTMF played an increasingly integral role in it. At the same time, the volume of empirical research drawing on the PTMF also grew rapidly.

Recognising this, the first study of my PhD thesis was a scoping review of the emergent empirical PTMF literature in the five years since its initial publication2. I conducted this scoping review in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Scoping Review Extension (PRISMA-ScR) and identified 17 relevant studies. The evidence base was diverse, with studies conducted across a range of disciplines (e.g. clinical/forensic/educational psychology), settings (e.g. inpatient psychiatric wards, prisons, schools) and populations (e.g. clinicians, prisoners, education professionals). Studies featured various methodologies (including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed), and utilised the PTMF in four main ways:

- PTMF-informed data collection

- PTMF-informed data analysis

- Experiences of/views on the PTMF

- PTMF-informed psychological practices

I concluded that while this evidence base has merit and is a welcome and promising development in the first five years since the publication of the PTMF, its heterogeneity makes it difficult to synthesise and draw meaningful conclusions from. Thus, in the next five years of the PTMF’s lifespan I recommended a deepening of the science, whereby a consistent and coherent approach to research utilising and/or evaluating the PTMF is necessary.

While the PTMF was the broad lens through which I came to understood violence, the VDP policy became the specific focus of my PhD research. In the IPS, a very small cohort of prisoners (< 1%) who are repeatedly engaged in serious violence and disruption are managed under the VDP policy. The original VDP policy was published by the IPS in January 2014, with the primary aim of protecting others from the risk posed by these prisoners. It was operationally driven, focusing on containment and physical security rather than intervention, progression, and relational security. A defining characteristic of the original VDP policy was the regular use of Control & Restraint (C&R) teams in almost all interactions with VDP policy prisoners. This practice was referred to locally as “barrier handling”.

In the second study of my PhD thesis, I aimed to generate a detailed description of practice under the previous VDP policy by qualitatively exploring the experiences and perspectives of prisoners (n = 4) and prison officers (n = 13)3. My inductive thematic analysis (TA) of 17 semi-structured interview transcripts resulted in the development of nine themes:

- Describing VDP policy prisoners

- Staff characteristics and approaches

- Describing the VDP policy regime

- The social environment

- The occupational environment

- Function of the VDP policy

- Impact of the VDP policy

- Factors influencing violence

- Responding to violence

Overall, participants described prisoners in mostly negative terms (e.g. manipulative, opportunistic), whilst also highlighting the influence of adverse childhood experiences on the development of their behaviour, and the related psychological (e.g. relieving tension) and strategic (e.g. securing better treatment) functions of their violence. Two types of staff were identified – the “right” staff (e.g. fair) and the “wrong” staff (e.g. antagonistic). The VDP policy regime was also described in negative terms (e.g. restrictive, solitary, controlled), with its inappropriateness and inconsistency highlighted. In describing the social environment, participants revealed that prisoner-prisoner interaction was limited in quantity, and staff-prisoner interaction was limited in quality. Prison officers reported positive staff team dynamics, but less positive relationships with management. In describing the occupational environment, prison officers highlighted the vast responsibilities of their role, for which they received limited training. Participants emphasised the operational focus of the original VDP policy, in which repeated serious violence was the main reason for designation and protection of others was the main purpose. The original VDP policy had adverse impacts on both prisoners (e.g. psychological wellbeing) and prison officers (e.g. desensitisation to violence), with both groups developing their own coping strategies for dealing with these impacts. In line with the existing prison violence literature, participants identified factors that influenced prison violence at the individual (e.g. drugs), interactional (e.g. staff misconduct) and environmental (e.g. staff shortages) levels. Participants ended interviews discussing how they thought violence should be managed in the IPS, which included a shift from reaction to prevention, and from containment to intervention. Overall, participants thought that the original VDP policy was both ineffective:

“It mirrors putting the child on the bold step for ten minutes. It’ll have a short-term effect, but long-term it doesn’t do anything.” —Prison Officer 8

And harmful:

“You’re just creating a monster.” —Prison Officer 2

Shortly after the implementation of the original VDP policy, and reflecting the results above, its shortcomings became evident. In 2016, the IPS formed a working group to look to the Close Supervision Centre (CSC) system in England and Wales as a possible alternative for Irish prisons. CSCs manage a cohort of prisoners similar to those under the VDP policy, but in a more psychologically informed way. This resulted in the opening of the National Violence Reduction Unit (NVRU) in November 2018 — which has become home to all VDP policy prisoners in the IPS — and a revised VDP policy. The NVRU aims to:

- reduce repeat violent offending

- improve the psychological health, wellbeing and pro-social behaviour of prisoners managed on the unit, and enhance relational outcomes for them

- develop a centre of excellence where staff demonstrate a high level of competence and expertise in dealing with prisoners with complex needs

- through this specialisation introduce a high quality of service, increased efficiencies and cost effectiveness across the prison estate.

To achieve these aims, the NVRU has taken steps to ensure that practice in the NVRU is psychologically informed at the policy (e.g. focus on intervention/progression); organisational (e.g. oversight by multi-disciplinary NVRU Committee); management (e.g. co-led by senior psychologist); environmental (e.g. enhanced provision of facilities/services/activities); staff (e.g. initial and ongoing psychological training for prison officers); and prisoner (e.g. intensive psychological assessment and intervention) levels.

The third4 and fourth5 studies of my PhD thesis, respectively, explored the experiences of prisoners and prison officers in the NVRU during its first year. Specifically, I explored their understandings of the origins, experiences, and expressions of violence through the lens of the PTMF. In both studies, prisoners (n = 3) and prison officers (n = 13) participated in semi-structured interviews informed by the core questions of the PTMF. Using a hybrid deductive (i.e. theory-driven) and inductive (i.e. data-driven) approach to TA, I identified six themes:

- Power

- Threat

- Meaning

- Threat response

- Function of threat response

- Moderating factors

These themes contained a number of sub-themes and codes, many of which were noted a priori in the PTMF, and some which were novel to participants’ accounts. It is impossible to do justice to the breadth and depth of these results in this article, so I encourage you to read the respective published articles for more detail. Taken together, these results illustrate clear pathways in the development of violent behaviour, from the negative operation of power through to associated threats and subjective meanings, ending in functional threat responses and moderated by exacerbating and ameliorating factors. Understanding the origins, experiences, and expressions of violence in this way is essential, if attempts to reduce it – as per the aim of the NVRU – are to be successful. Prison officers embody and develop these understandings in their interactions with prisoners, and the positive impact of this could be observed even in the first year of the NVRU. In an interview with one prisoner who had demonstrated a considerable reduction in violence since coming to the NVRU, I asked him why he thought this was. He replied:

“It’s them. I swear to God, it’s the officers. They’re just decent human beings. Actually seeing officers like that for me is mind-blowing. They don’t want to hurt you, which is totally not what I’m used to. I’m used to they want to hurt you, so you have to hurt them.”

While this quote highlights the impact that the NVRU has begun to have in the IPS, I have also observed the positive impact of my research throughout and following the completion of my PhD. I have shared my research nationally and internationally through conference presentations and journal publications, with the ultimate aim of enhancing understandings of the origins, experiences, and expressions of violence. I have proactively translated and disseminated my research findings in the IPS to various key stakeholders, who have welcomed, valued and actively engaged with its recommendations. Most importantly – at least to me – I have placed value on the voices of often-neglected and marginalised prisoners and prison officers, who are experts in their own lived experiences, and from whom I have learned so much throughout this research project.

Sources:

1https://researchrepository.ucd.ie/entities/publication/e52055c7-9b47-4f6f-b0fa-7b0fc463c4fe/details

2https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/bjop.12702

3https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1068316X.2022.2096885

4https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1068316X.2023.2228967

5https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1068316X.2024.2303485