Hans Toch, a towering figure in the academic discipline of criminology and criminal justice, died June 18 at his home in Albany, New York. Born April 17, 1930 in Vienna, Austria, Toch escaped the ravages of the holocaust, emigrating initially to Cuba and then to the United States. He earned his B.A. at Brooklyn College in 1952 and his Ph.D. in psychology at Princeton in 1955. He served in the U.S. Navy and was a Fulbright Fellow in Norway, a visiting Lecturer at Harvard, and a member of the psychology department at Michigan State University before being recruited in 1967 as a founding faculty member of the School of Criminal Justice at the State University of New York at Albany, the first program in the country to confer the Ph.D. degree in criminal justice.

Toch remained on the faculty at the University at Albany until his retirement in 2008, attaining the rank of Distinguished Professor and mentoring countless students and junior faculty members over the course of his lengthy tenure. Toch’s scholarship reflected a consistent humanistic bent and a concern for representing the viewpoints, understandings, and humanity of the subjects of his writings: offenders, police officers, the incarcerated, and correctional officers. He authored more than 30 books including such classics as Violent Men: An Inquiry Into the Psychology of Violence; Living in Prison: The Ecology of Survival; and Stress in Policing.

He received the August Vollmer Award from the American Society of Criminology in 2001, and in 2005 he was recognized with the Prix DeGreff award for distinction in clinical criminology by the International Society of Criminology. He was a fellow of the American Society of Criminology and of the American Psychological Association, and in 1996 served as president of the American Association for Forensic Psychology. This Association later became known as the International Association for Correctional and Forensic Psychology (IACFP).

Throughout his academic career, Toch touched legions of friends, colleagues, and students, who remember him for his unique combination of commanding intellect, compassionate humanitarianism, and unflagging good humor. Among their memories are his doting fondness for his pet dogs, his booming laugh, and, until forced to relinquish them, his ever-present cigars and their malodorous fumes. His opinions, frequently fueled by righteous indignation about perceived injustices, were unfiltered and issued loudly, without apology and with supreme self-confidence.

As an obsessional and expert collector of antiques and art, Toch enjoyed nothing more than death-defying drives (automotive skills were not among his strengths) to remote, country antique stores to browse for Shaker furniture or porcelain dogs and good-naturedly haggle with the owner over “extortionate” prices. He cultivated the image of a curmudgeonly grouch, but all who came to know him soon discovered the heart of gold that lurked beneath the ostensibly gruff exterior. For his many friends and colleagues, Hans is fondly remembered for his brilliant intellect, his ineffable buoyancy, quick wit, eloquent prose, and his unfailing commitment and enduring contributions to rigorous social scientific scholarship and social justice.

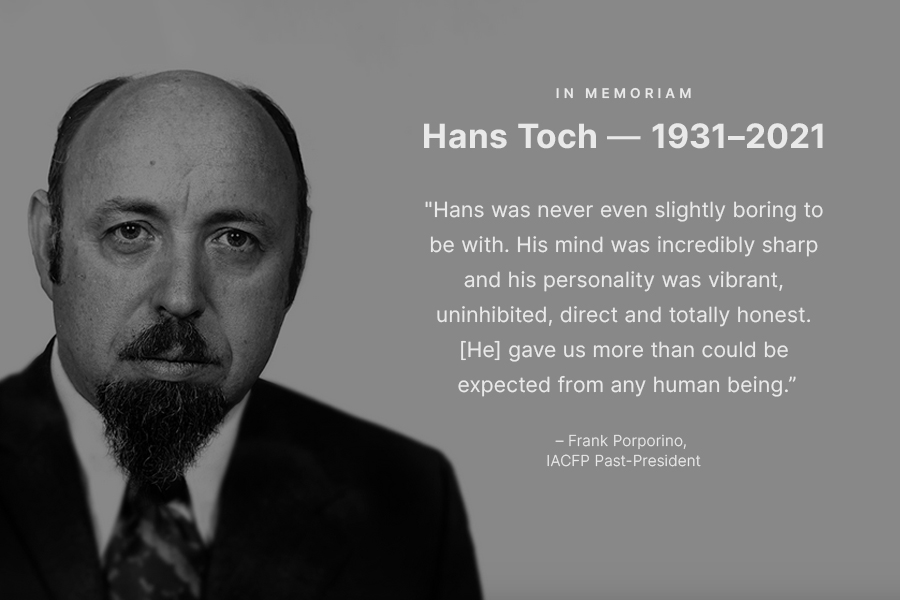

Frank Porporino, IACFP Past-President, shared this in remembrance of his friend:

“Hans Toch has been on the top of my short-list of scholar heroes for decades. It’s sad to accept that I won’t be reading another of his thoughtful, beautifully written articles, chapters or books … but what a hell of a scholarly legacy he has left us.

I was lost as a young, naïve psychologist in the early 70s working in a maximum-security prison in Canada … I felt confused … didn’t at all understand what was going on around me in this strange environment. Coming across some of Hans’s work … most significantly Violent Men and Living in Prison … widened my eyes and nourished my mind! I was stuck with working to humanize corrections for the rest of my career.

Hans was my external advisor for my Ph.D. thesis. He gave me a hard time with his usual penetrating questioning of my interpretations and understandings. We became friends and stayed in touch for many years. I will always fondly remember his continued penetrating questioning of my ideas as we drank single malt scotch together quite often in Scotland, late into the night. There was nothing Hans enjoyed more than a good debate!! We joined in critiquing the ‘psychopathy’ mob at a wonderful week-long gathering of experts at the Il Ciocco resort in Tuscany. We took side trips to Lucca and Florence, and Hans enthralled me with stories of his incredible childhood. I visited with him at his museum-like home in Albany several times … more scotch, more penetrating questioning, and a delightful education in antique collecting.

Hans was never even slightly boring to be with. His mind was incredibly sharp and his personality was vibrant, uninhibited, direct and totally honest. He inspired me and gave me determination, hope and purpose for my own career. He will be with me until my own time comes to fly with the angels. RIP my dear friend. You gave us more than could be expected from any human being.”

*This article is based on reminisces and memories shared by his colleagues following his death.