First, I want to thank the International Association for Correctional and Forensic Psychology (IACFP) Board of Directors for awarding me the Student Research Grant Award in support of my dissertation project, “Implementing a brief treatment program for justice-involved people with mental illness in jail: A mixed-methods hybrid 1 randomized controlled trial.” I am grateful not only for IACFP’s generosity, but also for the recognition of this project, in which we are providing treatment to people with serious mental illness in jail—thank you for supporting this work and helping make this study possible.

Background

There are five times more people with serious mental illness in jails (26%) than in the U.S. general population (4.5%; Bronson & Berzofsky, 2017). Additionally, about one-half of people with mental illness involved in the criminal justice system (PMI-CJ) are re-arrested within four years of release (Wilson et al., 2011). As the entry point to the criminal justice system, jail offers an opportunity to attend to PMI-CJ’s treatment needs to promote the reduction of recidivism and improved mental health. Yet, despite the over-representation of people with mental illness in jails, and evidence that treating psychiatric symptoms and criminal risk factors can reduce PMI-CJ’s criminal justice involvement (Morgan et al., 2012; Skeem et al., 2011), there is limited treatment programming available in jail (Bronson & Berzofsky, 2017).

Changing Lives and Changing Outcomes (CLCO; Morgan et al., 2018) is a therapeutic treatment program that was developed to meet PMI-CJ’s need for integrated services. Using cognitive-behavioral and social learning tenants, CLCO addresses both mental illness and criminal risk simultaneously throughout treatment to reduce psychiatric and criminal recidivism (Morgan et al., 2018). In full, CLCO is comprised of 76 treatment sessions across nine modules; each CLCO session incorporates psychoeducational components, including hand-outs and homework assignments. CLCO has been found to be effective in reducing psychiatric and criminal risk symptoms of treatment recipients in prison and residential treatment programs (Gaspar et al., 2019; Morgan et al., 2014; Scanlon & Morgan, 2019; Van Horn et al., 2019).

The full CLCO program targets a broad set of issues related to mental illness and criminal risk for this population (e.g., substance use, associates, medication adherence). One CLCO module (Mental Illness and Criminalness Awareness) was identified by the lead developer of CLCO as a potential initial treatment for PMI-CJ in cases where the full program could not be delivered; this specific module most directly targets mental illness and criminal behavior. I conducted a pilot study to test the effectiveness of CLCO’s Mental Illness and Criminalness Awareness module in a residential treatment facility (Scanlon & Morgan, 2019). The overall sample of 58 adult male PMI-CJ showed significant improvements in almost all measures of psychiatric and criminal symptoms, except for proactive and overall criminal thinking (Scanlon & Morgan, 2019).

The Current Study

The aim of this dissertation project was to conduct a mixed-methods randomized controlled trial of a 9-session Mental Illness and Criminalness Awareness CLCO treatment module for people with serious mental illness currently incarcerated in the Lubbock (Texas) County Detention Center. The primary goal of the study was to examine the CLCO module’s effectiveness compared to the jail’s treatment as usual (e.g., medication, crisis management) in producing pre-to-post-treatment reductions in self-reported severity of psychiatric symptoms, criminal thinking, and antisocial attitudes; reductions in frequency of disciplinary infractions per file review; and improvements in self-reported psychological well-being and illness management among PMI-CJ. A secondary aim of the study was to test the implementation of the CLCO module through focus group discussions, in which treatment recipients are asked about their perceptions of the program’s feasibility and acceptability.

The study was conducted as a randomized controlled trial for 50 days. During this time, of the 10 participants randomized to the control condition, only one completed post-assessments. Additionally, only 23% of those in the CLCO treatment condition completed the treatment program. Notably, almost all of this attrition was due to involuntary drop-out (e.g., being moved to an inaccessible housing unit, being released). Due to the unexpectedly low completion rate, it was determined that a randomized controlled trial of this treatment in the jail setting was premature; therefore, the control condition was eliminated and all participants moving forward will receive the CLCO treatment.

Findings to Date

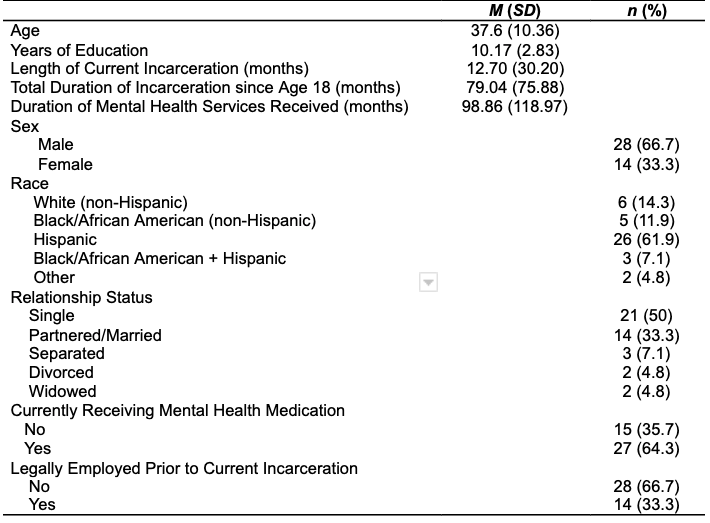

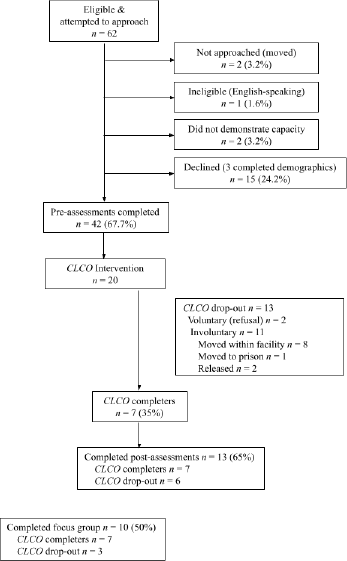

The demographics of the 42 participants who completed pre-treatment measures are presented in Table 1. A CONSORT diagram is presented to illustrate participants’ progress through recruitment, intervention, and assessment in the current study (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Demographics (N=42)

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

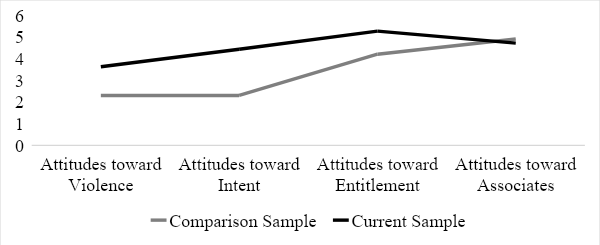

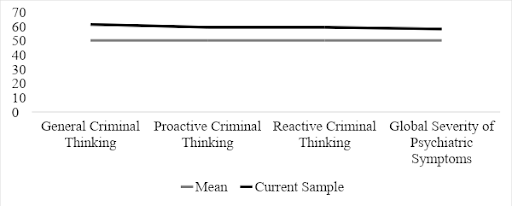

The current sample’s pre-treatment scores on antisocial attitudes were measured per the Measure of Criminal Attitudes and Associates (MCAA; Mills & Kroner, 2001). The sample demonstrated higher mean pre-treatment scores on antisocial attitudes toward violence, attitudes toward antisocial intent, and attitudes toward entitlement compared to the means of a comparison group of justice-involved people, which were published in the MCAA User Guide (Mills & Kroner, 2001); the current sample’s mean pre-treatment attitudes toward associates were roughly consistent with that of the comparison sample (Figure 2). The sample’s pre-treatment criminal thinking scores and global psychiatric symptom severity are presented in Figure 3 as T-scores; the sample’s scores are higher than the mean T-score of 50 across all scales.

Figure 2.

Mean Scores of the Current Sample’s Pre-treatment Antisocial Attitudes and Comparison Group’s Antisocial Attitudes

Note. Antisocial Attitudes scores were assessed by the Measure of Criminal Attitudes and Associates (MCAA; Mills & Kroner, 2001). The Comparison Sample means were taken from the MCAA User Guide (N = 342; Mills & Kroner, 2001).

Figure 3.

Current Sample’s Pre-treatment T-Scores for Criminal Thinking and Global Severity of Psychiatric Symptoms (N – 42)

Note. Criminal Thinking scores assessed by the Psychological Inventory of Criminal Thinking Styles (Walters, 2006). Global Severity of Psychiatric Symptoms assessed by the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis, 1983). T-scores presented above have a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10.

All treatment recipients who were available to do so (e.g., not released from the facility; n = 10) completed focus group discussions on their perceptions of the CLCO module’s implementation. The qualitative data from these discussions has not yet been analyzed. However, at the end of each focus group, participants were asked if they perceived the program’s implementation in the jail to be feasible (yes/no) and acceptable (yes/no). All 10 participants unanimously indicated they perceived the treatment to be both feasible and acceptable.

Advancing the Science of Correctional and Forensic Psychology

Because only seven participants have completed the CLCO treatment program to date, no conclusions can be drawn about the program’s effectiveness. However, the preliminary findings that 100% of treatment recipients who completed the focus group discussions agreed the program was both feasible and acceptable, indicate promising perceptions of this abbreviated intervention in jail.

It should be noted that while participants reported perceptions of the program’s feasibility, only seven of the 10 focus group discussion participants completed the program, due to extenuating circumstances (e.g., early release, placement in restrictive housing). Therefore, in addition to providing efficacious treatments, this study aims to document examples of systemic issues that might limit PMI-CJ’s access to treatment, thereby advancing the science of implementation within correctional and forensic psychology. Finally, by seeking to understand treatment recipients’ perceptions of interventions, we can reduce barriers and improve service delivery and utilization in correctional and forensic psychology.

* References available upon request.

Faith Scanlon is a fifth-year doctoral candidate in Texas Tech University’s Counseling Psychology Ph.D. program. Her research examines the provision of treatment among people who are involved in the justice system; and antecedent factors of criminal justice-involvement, including trauma, mental illness, and criminal risk. Faith has produced 10 peer-reviewed publications, 18 national and international conference presentations, and has received three awards recognizing her research as a graduate student. After completing her degree, she hopes to continue her research program as an academic.