Criminal Justice Reform & The Man in Black

It was on July, 1972 that musician Johnny Cash (“the ‘Man in Black”), having already performed at a number of prisons in Texas and elsewhere, appeared in front of a Senate subcommittee on prison reform, and lobbied for criminal justice reform in America; an advocate position he maintained during most of his 30-year performance career.

Since Mr. Cash’s 1972 appearance, America evolved into a “tough on crime” society, incarcerating more individuals than any other developed country in the world—currently approximating over 2.3 million individuals,with another estimated 6 million individuals on legal supervision—and remaining the only developed Western country in which the death penalty is still legal.

During this time, those who have supported America’s approach to crime management typically have maintained that committing a crime is generally a willful individual action, and—regardless of cultural, racial, economic, or other variables—individuals should be held accountable for their crimes in ways that serve as just retribution and provide a deterrent to future crimes in order to protect the public and maintain social order. Supporters see America’s seemingly punitive sentencing practices (e.g., minimum sentencing and “three strikes”) and incarceration rates as a necessary response to crime rates, without racial or economic bias in either policing or sentencing. Proponents of the conservative “tough on crime” approach believe it has had a demonstrable impact on reducing crime rates, and so has been worth the cost to taxpayers.

Critics of America’s criminal justice system have alleged the “tough on crime” philosophy contributed to its evolution into a politically weaponized, economically costly and inefficient, economically- and racially-biased system that has also become an under-resourced repository for the mentally ill and drug-addicted. This process facilitated the development of a profit-seeking “prison industrial complex.” Critics have alleged that being “tough on crime” over the past five decades has not had any easily demonstrable impact on lowering crime rates; some claiming it decreased rather than increased public safety, and consequently was not worth the cost to taxpayers.

Advocates of maintaining the status quo have often been characterized by reformists as not being “smart on crime.” Those that resist reform have often characterized reformists as being “soft on crime.” America nonetheless remains the world’s leading incarcerator.

Although there seems to be increasing evidence that criminal justice reform is garnering more public and political support, the “smart vs. soft” debate continues. Joe Biden’s reform plans as outlined in Politico (Forgey, 7/23/19), encompassed eliminating the death penalty, targeting factors like illiteracy and child abuse, confronting racial and income-based disparities, and prosecutorial discrimination. In contrast, President Trump has maintained that “Democrats don’t give a damn about crime” (1/10/2019).

Given the impact on millions of legally-involved individuals and the cost to taxpayers, the stakes of the reform-vs no reform debate are significant with regard to public safety and social order. So, if elected president, will Mr. Biden’s criminal justice reform efforts be more successful than Mr. Cash’s and of those that followed during the past five decades, or will those that have and continue to oppose any significant reform of America’s criminal justice system win out in the interests of public safety? Is there a way to consider this question that leads to a deeper understanding by supporters of both sides of this debate without continuing arguments over which viewpoint is better or who’s to blame for whatever happens next? One that might facilitate a common point of view?

“The particular patterns of synaptic connections in an individual’s brain, and the information encoded by these connections, are the keys to who that person is.” (LeDoux, 2002, p. 3)

The BRAIN Initiative

On April 2nd, 2013, the Obama administration announced the “BRAIN Initiative (Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies),” with the goal of supporting the development and application of innovative technologies that can contribute to a dynamic understanding of human brain function.

Perhaps as a byproduct of President Obama’s BRAIN initiative, a plethora of popular brain-related books written for the lay consumer emerged, with titles like Use Your Brain to Change Your Age (Amen, 2012), Rewire Your Brain (Arden, 2010), The Emotional Life of Your Brain (Davidson and Begley, 2012), and You Are Not Your Brain (Schwartz & Gladding, 2012), as well as for clinicians (e.g., Neuroscience for Clinicians (Sinpkins and Simpkins, 2013), and The Neuroscience of Psychotherapy (Cozolino, 2010). Neuroscience-based workshops for CEU credits have become part and parcel of clinical practice.

The Connection

One might wonder, “What possible connection does exploring and understanding the functions of the human brain have to do with enduring advocacy of and/or resistance to reforming America’s criminal justice system? Consider, everyone on both sides of the criminal justice reform debate has a brain, and, as University of Wisconsin professor Deric Bownds’ opines In his book Biology of the Mind, our brains evolved mainly to “keep us out of trouble” (Bownds, 1999, chapter 2, p. 12).

“In the case of the brain, there is just the brain—there is no separate thing, me, existing apart from my brain. My brain does what brains do; there is no separate me that reads my brain’s maps.” (Churchland, 2013, p. 34)

Our Brains Are Us

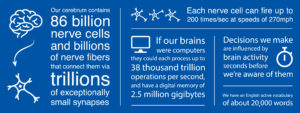

Since the initiation of the BRAIN initiative, neuroscientists have learned that our brains have genetically and physiologically evolved to be very able to perform a multitude of exceptionally complex tasks.

Neuroscientific research has revealed that we feel, think, decide, and behave only as our brains determine, based on the accumulative neural interactions of our experiences as they relate to our environment at the time, interactions outside of our conscious awareness and voluntary control. As molecular biologist and zoologist Deric Bownds observed, “As we look further inside the brain, we become increasingly convinced that there doesn’t appear to be anyone at home. We don’t find a specific place where there is a thinker or a feeler or an actor,” (Bownds, 1999, Chapter 1, p. 8). In short, our brains, in their wholeness, are us.

“… the reality is that our brains are vast networks of neurons…that work together to generate our experience of the world. Of particular importance are networks of associations, bundles of thoughts, feelings, images, and ideas that have become connected over time.” (Westen, 2007, p. 3)

So what does all this information about brain functioning have to do with reforming our criminal justice system? Easy. Our current criminal justice system is the sum product of the functioning of the brains of those who composed and sustained it; society, politicians, legislators, and criminals alike.

Resistance to Reform

Why the brain’s enduring resistance to reforming America’s criminal justice system? I posit: Trust and Mistrust.

“Interpersonal trust as a dynamic belief pervades nearly every social aspect of our daily lives, from personal relationships to organizational interactions encompassing social, economic, and political exchange.” (Krueger and Grafman, 2013, p. xiii)

In order for our brains to keep us out of trouble, individual and social survival depends on the development of our abilities to discern what and who to trust (i.e., it/they won’t hurt us) and who to mistrust (i.e., they/it might, or will, hurt us). As Steven Stoney concluded, “There could be no civilization, enduring health, or mental wellness without trust. The most ordinary interpersonal, commercial, medical, and legal interactions would be impossible without some degree of trust” (Stoney, 2014).

“Trust” is a concept we attribute to a belief that we are safe from harm, leading to a physiological sense of relaxation and bonding pleasure.

Neuroscientific research has discovered that a feeling or sense of trust involves the neurotransmitter oxytocin, released when a person comes to believe they need not be afraid of another. Further, the neural pathways resulting in a sense of trust are genetically inherited. This makes evolutionary sense because infants need to have an instinct to bond with their caregivers. Among adults, researchers have found that specific areas of the brain and neurotransmitters (e.g., oxytocin and dopamine) are also involved in facilitating a sense of trust in social interactions.

“Mistrust,” on the other hand, is what we call a physiological state of unease, anxiety, tension, and fear or hate of things or others that might or have hurt us; a suspected or actual threat to some important aspect of our survival, both personally and interpersonally, leading to a conscious desire to avoid such threats. It is central to keeping us out of trouble.

Neuroscientific examination of mistrust is also informing. Researchers have found that mistrust is not at the other end of a neural “trust-mistrust” continuum as one might expect, but that a development of mistrust activates a different set of pre-existing neural networks and neurotransmitters. “Mistrust” involves activation of our amygdala with the release of adrenaline, activating related neural networks associated with experiences of fear and anxiety. This activation facilitates the learning of which threats to avoid, and is stored in other brain areas for future reference. In contrast to trust networks, mistrust networks are not heritable (e.g., Reiman, Schilke, and Cook, 2017), but develop later as a result of an individual’s life experiences. This too makes evolutionary sense, since our post-infant survival depends upon remembering and avoiding those things that could or do pose a threat to our survival.

When a situation is not clear, neuroscientific research has suggested that ambiguous information—that is, information that is not clearly a threat or not a threat—can result in an initial emotionally negative avoidance (mistrust) response, and that this negative response is more easily activated and assumes priority over a possible positive (trust) response (e.g., Filkowski, Anderson & Haas, 2016). This makes absolute survival sense; if one is not sure whether to trust or mistrust, be cautious. Be suspicious. Best to avoid it until we’re certain.

Criminal Justice Reform: Can we ever really trust a criminal in our community?

From a neuroscience perspective, it is easy to comprehend why there has been enduring sociopolitical resistance to reforming America’s criminal justice system. Criminals have already exhibited an inability to conform to the social laws, mores, and standards of conduct we expect in the interests of public safety and social order. As far as our brains are concerned, criminals are potential trouble, and are simply not to be trusted to be law-abiding citizens after experiencing a negative consequence or completing a prescribed punishment for their behaviors. Consequently, when it comes to criminal justice “reform” that involves criminals being treated more humanely, being punished less severely, maintained in or released early to our communities, our neural “mistrust” networks are easily activated and maintained.

The Challenge of Criminal Justice Reform efforts

If professor Bownds’ premise that our brains evolved mainly to keep us out of trouble makes sense (and it does to me), we have an enduring brain-based basis for sociopolitical resistance to reforming America’s criminal justice system. Advocates of America’s “tough on crime” philosophy ostensibly want to keep Americans “out of trouble.”

Given our concerns about crime and criminals, one has to wonder about those who advocate reform of our criminal justice system. How can they have the same “keep us out of trouble” goals by reducing offender sentences, releasing inmates early, eliminating the death penalty, etc? What’s wrong with their brains? What if the answer is “nothing?” Are there normal brain functions that can explain the efforts of those who want to reform America’s criminal justice system in ways that might also keep us out of trouble? Neuroscience suggests there are, and those will be discussed in later contributions to this newsletter.

Meanwhile, it seems clear that the one common denominator that explains both sides of this “tough vs. soft on crime” debate is brain function. One does not have to be a neuroscientist to understand that our brains influence every aspect of our feelings, thoughts, and behaviors about crime—often in ways outside our conscious awareness. Is it therefore possible that by incorporating what is known about how our brains normally function, a collaborative and blame-free dialogue regarding America’s criminal justice system (and elsewhere, for that matter) can take place that avoids the enduring sociopolitical arguments over who is “smarter” or “softer” on crime, while addressing the public safety and social order concerns of both sides? I believe it is.

*Specific references available upon request.

About the Author

Richard Althouse, Ph.D. is Secretary of the Executive Board of IACFP. He has had 37 years of experience as a clinical/correctional/forensic psychologist in both staff and supervisory positions in the Wisconsin Department of Corrections or the Wisconsin Department of Health and Social Services. Since retirement, Dr. Althouse has remained active in matters related to the criminal justice system and provides expert testimony in litigation involving inmate suicides.

Richard Althouse, Ph.D. is Secretary of the Executive Board of IACFP. He has had 37 years of experience as a clinical/correctional/forensic psychologist in both staff and supervisory positions in the Wisconsin Department of Corrections or the Wisconsin Department of Health and Social Services. Since retirement, Dr. Althouse has remained active in matters related to the criminal justice system and provides expert testimony in litigation involving inmate suicides.