This month, Frank J. Porporino, Ph.D., shares highlights from responses he prepared to interview questions focusing on the efficacy of prison vs. probation.

Question 1

In one of your keynote speeches to the World Congress on Probation, you argued that reliance on incarceration is cost-ineffective and that probation can lower the cost of criminal justice. Can you share some of the data on this? What are the economic and cost-efficiency benefits of probation sanctions instead of custodial sanctions?

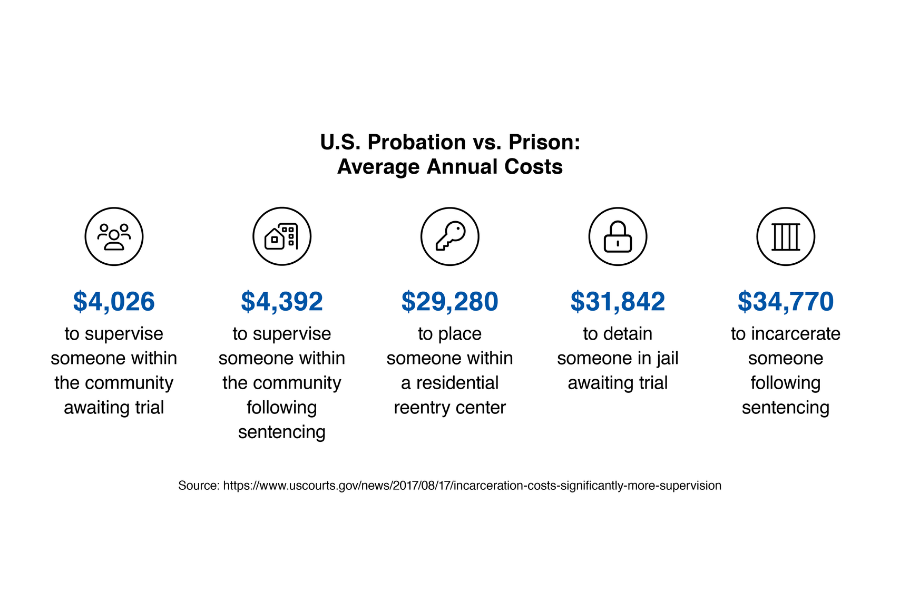

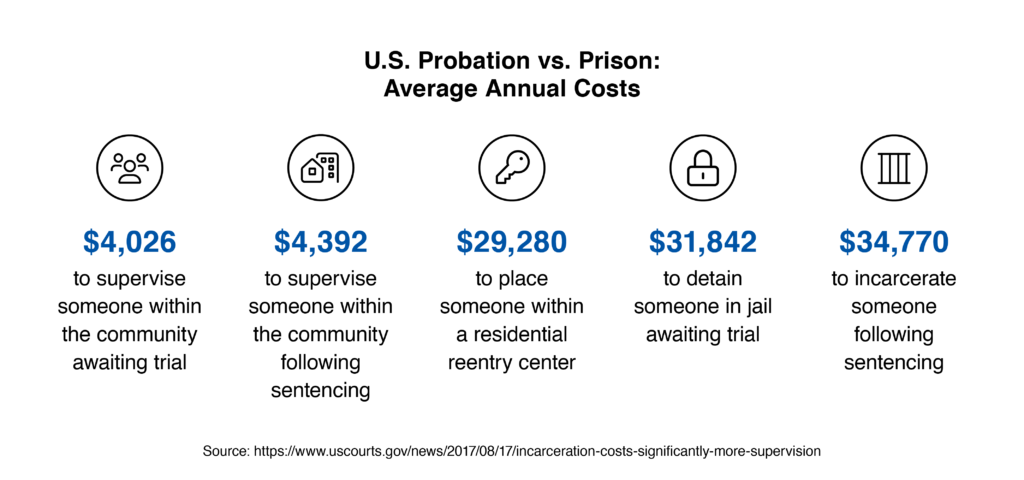

FP: If we look at just basic cost estimates of imprisonment vs. probation … it’s like comparing the size of a grapefruit vs. a grape … in the U.S., for example, the cost of incarcerating someone comes in at about nine times the cost of probation supervision. In Canada, where probation caseloads are much smaller, the difference is less dramatic, but incarceration is nonetheless six times the cost of probation.

We can make the same comparisons for most countries around the world that have both options … but as is well known, probation unfortunately is not even available as a sanction in many countries … leaving the judiciary with only the expensive option of locking people up!

But this is only the beginning of the story … because when we factor in the many other collateral costs of imprisonment … then the difference in social costs becomes even more striking.

Imprisonment stigmatizes and disconnects individuals and de-stabilizes communities … with devastating effects on relationships with spouses and children, health and mental health, and future economic status.

- Criminologists refer to “million-dollar blocks” in America to highlight the fact that it costs upwards to a million dollars annually to incarcerate individuals originating from only one inner city residential block. Concentrated removal of adult parental role models breaks families apart and destabilizes communities.

- Imprisonment disconnects individuals from employment … and there are severe long-term consequences. It’s been estimated that imprisonment reduces subsequent lifelong annual earnings by about 1/3 since we know that “ex-prisoners” can access mostly only bad jobs with poor pay, high turnover, and limited potential for advancement.

- In the family that is left behind, poverty increases; and dependence on social welfare and other metal health and addiction services rises exponentially.

- About 1/2 of all “prisoners” are also parents of children under 18. Research has shown that these young children are at greater risk of experiencing serious behavioral problems, drug abuse increases … teenage pregnancies occur more frequently and alienation from pro-social norms becomes more common.

- Parental incarceration increases the likelihood of early school dropout and later delinquency by 3 to 4 times … and quite sadly, it’s been estimated that almost 6 in 10 young Black males who don’t finish high school in America will end up in prison during their lifetimes.

Incarceration, in essence, has a series of knock-off effects in reducing community-level informal social control, increasing the strain on already taxed social services and spiraling into less rather than more public safety.

Of course, we could argue that “cost” is not the real issue … what we want from our CJS is public safety. If imprisonment can give us more or better public safety … then it’s worth the COST! And so here is where the prison-as-deterrence stance completely breaks down.

The evidence is clear. In one recent analysis looking at thousands of offenders matched on risk, criminal background, etc. … it was found that, compared to probation, incarceration increased the odds of recidivism for men by 140%.1

A recent significant review of all the best research in this area … referred to technically as a meta-analysis … has elevated the status of the evidence to “criminological fact.” There should be no more argument about whether prison can do a better job than probation in reducing reoffending and contributing to public safety … it simply just can’t!2

Essentially, in choosing imprisonment over probation or other community sanctions, we are choosing a much more expensive alternative that has been proven to be less effective … and that isn’t very “smart” social policy … its actually quite dumb!

We really need to remember that if incarceration could create safer communities, then the U.S. should be the safest country in the world! It’s actually Japan that is among the safest countries in the world … and their rate of incarceration is not 1/2 or 1/3 that of the US’s … it’s about 1/15th!

Question 2

You’ve also mentioned that incarceration is unnecessary and de-legitimizes the ultimate aim of the criminal justice system to preserve social order. How so?

FP: Criminologists are looking more and more at the role of “legitimacy” in reducing crime. In neighborhoods where incarceration rates are highest, it’s been shown that citizens are more likely to view the police as unfair, disproportional, and disrespectful. Citizens are consequently less likely to comply, losing respect for governmental authority and withdrawing from social institutions and political life. Criminologists refer to this as “custodial citizenship” … the creation of large minorities of disempowered, cynical, second class citizens who have lost faith and hope that social institutions can preserve the social order.

Public safety should be the ultimate aim of the CJS. But just getting “tough on crime” without getting smart about how we do it is a fool’s path. It leads to depletion of economic and social resources that could better target other issues that breed crime … (e.g., poverty, lack of educational opportunities, poor (or no) housing, unemployment, health …etc.). This is a hard lesson that’s been learned in America after several decades of mass incarceration that is now being challenged more and more as unsustainable and ineffective.

What most people don’t understand about incarceration is that it has the least punitive or deterrent effect on the highest risk individuals. Those who are most committed to criminal lifestyles are not badly affected by prison. They don’t really mind it. It’s the cost of doing business, and it keeps them connected (even better connected) to the criminal subculture. It’s the lower-risk individuals who mind it most … who experience the greatest pains of imprisonment, and who are often the most damaged … and it’s those lower risk individuals who should be on probation. I could argue that even some higher-risk individuals will find probation more painful than imprisonment … the need to follow conditions that restrict their freedom and having to live under the constant threat of being returned to prison. There’s actually some evidence to support the view that probation can often be more “painful” than prison.

At the end of the day, we have to accept that incarceration doesn’t typically nudge or encourage any change in behavior or mindset … it often will serve as just a period of “deepfreeze,” where the focus is on “doing time” as painlessly as possible! Prison doesn’t change criminal behavior; it just interrupts it for a while. For every kind of intervention that the research has looked at, it’s clear that the interventions have more effect when used in the community instead of prison.

Question 3

What is necessary to make probation an effective response to crime? What does the research say about this?

FP: Community sanctions are effective if they’re tailored to the individual and their particular needs. Of course, that means you need quality information about the offender and their psychological and social background.

Probation practice essentially should focus on 4 things:

- Correcting the criminal thinking and attitudes of offenders;

- Treatment (for addiction or mental health issues);

- Giving assistance that is practical, appropriate and timely (linking to employment/accommodation); and

- Then ensuring there is some level of full reintegration.

In doing those things, it’s all about relationships … and there is a particular blending of style and skills that’s been shown over and over again as core in importance in working effectively with offenders. An insightful analysis of Therapeutic Correctional Relationships by Dr. Sarah Lewis from the UK narrows in on five key dimensions: acceptance, respect, support, empathy, and belief.3 When a probation officer can develop this kind of relationship with an offender … when they get that relationship right … the research shows that reoffending rates can be reduced significantly.

On the other hand, if you use probation, for example, as it’s often now done in many jurisdictions … where all that’s involved is that a probationer has to periodically check in at a kiosk or on their mobile phone … then there’s no connection and that’s not probation! That’s surveillance … and probation that is just surveillance … no matter how intensive … doesn’t work.

Question 4

Is there other evidence that supports the benefits of a strong probation system?

FP: Probation at its best can create pathways to reintegrate offenders as full, contributing citizens. Prison, on the other hand, topically creates more roadblocks and barriers for individuals to hurdle over. A prison term in many jurisdictions in America makes you ineligible for a host of employment opportunities (e.g., truck driver, nurse, plumber, cosmetician …etc.), health and welfare benefits, food stamps, public housing, education assistance, obtaining a driver’s license, enlisting in the military, becoming a foster parent, obtaining a federal security clearance, and even serving on jury duty or exercising your democratic right to vote. Now I would ask … how can all of that possibly lead to “citizenship?”

There is perhaps a valid argument to make that one of the aims of sentencing should be “just deserts” or retribution. But I would argue that we should be honest and not pretend that has anything to do with public safety. It has to do with public appeasement. Our CJS (and our political leaders) should do more than just appease the public and try to assuage their fears of crime. A more responsible and moral approach would be to work towards educating the public to accept what is ultimately in their best interest … much more limited use of imprisonment as only a last resort.

Question 5

At your presentation during the 3rd World Congress on Probation in Japan, you noted that we must work to create a truly integrated, evidence-informed model of practice – and not accept the piecemeal, token, and segmented. What do you mean by this? Why is this important?

FP: Integration means that the various components of the CJS are truly working together towards the common goal of cost-effective use of resources for greatest public safety value. It’s been demonstrated, for example, that jurisdictions that have a greater proportion of “prosecutors” per capita will make greater use of imprisonment. If prosecutors and the judiciary believe that imprisonment is the only effective deterrent … then incarceration rates go up.

Let me give you an example of poorly integrated practice. An Association for which I serve as Past President … the International Association for Correctional & Forensic Psychology … has been conducting an international scoping study to look at services for the mentally ill within community corrections … and we’re finding incredible variation. We know that our prisons are clogged with the mentally ill … they’ve become the new asylums. But we also know that diversion programs involving law enforcement can be very effective in keeping the mentally ill out of prison. Enhanced specialty mental health services, like Mental Health Crisis Teams and Assertive Community Treatment, have been shown repeatedly to work at a cost of only a fraction of what incarceration costs. It’s not rocket science to figure out how one component of the CJS can affect another … and integration means that all the cylinders should fire in unison.

Effective and integrated probation practice means we attend to what Fergus McNeill refers to as the four key aspects of rehabilitation … not just the personal, but the social, legal, and moral. You have to give offenders the social assistance that they need and help them overcome some of the very real barriers to employment and housing, for example. The stigma of the criminal conviction has to be dealt with. Taking away the right to vote, for example, seems to be an ironic policy when our aim should be to reintegrate, not to disenfranchise! Offenders will often have a strong moral motive of reparation … wanting to “give back” in some way and begin to feel they have earned their re-acceptance into community. Probation can facilitate that moral work of earning acceptance as full citizens.

Fundamentally, you can’t run a probation service on its own; it needs to be integrated and connected with other community supports and services and close ties with NGOs. When you have impoverished (and sometimes even quite unwelcoming) community services, it’s very difficult to run a probation service. One small piece of the pie … like electronic monitoring or an anger management or domestic violence program … doesn’t mean we are doing good probation!

Question 6

Different countries have different criminal justice systems, and they don’t have the same volume of resources. How can countries approach the development of their own probation service?

FP: Just like with access to the COVID vaccine … there is, sadly, incredible disparity in resources available in different countries to develop probation services … but I believe every country can at least begin to find their own solution at their own pace.

Let me give you an example of some work I’ve done in Africa in Namibia. There was strong commitment to reform, but limited resources to move forward in establishing community options.

Enabling legislation had to be developed to allow for community options … done!

Finland stepped in with resources for a Community Service Order pilot … done!

But it didn’t work initially. It stalled primarily because prosecutors and the judiciary simply didn’t understand Community Service Orders … who should get it, how would offenders be held accountable, who would supervise, what exactly would offenders be doing … etc.?

A broad-scale education campaign was mounted … involving judges, prosecutors, prospective employers, families, and other community stakeholders … etc. Mechanisms were developed to involve families and employers in providing at least some level of structured supervision. Credibility grew … and CSO’s and post-release community supervision are now in common use in Namibia.

Some work I did in Japan a few years ago exposed me to their incredibly well developed VPO [Volunteer Police Officer] system … where they make use of some 40k volunteers they call Hogoshi … not just to support the traditional focus of probation … to Advise, Assist, and Befriend … but to help in community engagement and local enhancement of community resources throughout the country. It’s a very effective, low-cost model that’s now being used in many other Asean countries and in Africa!

I believe every country can find a solution to make use of community options … where you begin by building capacity with what you have … establish credibility … and then keep working to build further capacity.

Question 7

You’re suggesting more reliance on volunteers … as they are doing perhaps in Japan and Africa. But aren’t there obvious cultural differences that have to be looked at … especially in terms of attitudes towards ex-offenders?

FP: Obviously, there are cultural differences. In Japan for, example, it is considered a kind of duty and genuine honor to give back to one’s community in some fashion as a volunteer. One of the most significant informal functions of VPOs in Japan is to look for, identify, and recruit other VPOs. In most western correctional jurisdictions, recruitment of volunteers is more a matter of simply waiting for them to come to us … rather than making any meaningful and active effort to go to them! Some volunteers may be attracted more because they are curious or intrigued – and not because of any particular dedication to support and assist others who are troubled and disadvantaged. The right volunteers can make a huge difference; the wrong kinds of volunteers can lead to cynicism and suspicion among corrections professions towards the whole idea of volunteers.

We also have to stop thinking of volunteers as just a “free” resource. In Japan, VPOs have clearly defined roles, and they aren’t just taken for granted. They are supported, respected, and acknowledged, even at the highest levels of their Ministry of Justice.

It’s true that the public is often punitive and holds a stereotyped view of ex-offenders as dangerous, unpredictable, and uncooperative. But these views can change … even at the societal level. A very notable example is the Singapore Yellow Ribbon Project, launched in 2004 as a broad-scale annual campaign to engage Singaporeans in supporting ways of giving offenders a “second chance.” The incredible achievements of the Yellow Ribbon Project have been documented extensively, including the explosive growth in number of employers and community volunteers who are now contributing concretely to giving individuals that “second chance.”

Footnotes:

1 Caudy M.S., Tillyer M.S., Tillyer R. (2018). Jail Versus Probation: A Gender-Specific Test of Differential Effectiveness and Moderators of Sanction Effects. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 5(7): 949-968.

2 Petrich D.M., Pratt T.C., Jonson C.L., & Cullen, F.T. (2021). Custodial Sanctions and Reoffending: A Meta-Analytic Review. Crime and Justice, vol. 50.

Smith, P., Goggin, C, & Gendreau, P. (2002). The Effects of Prison Sentences and Intermediate Sanctions on Recidivism: General Effects and Individual Differences. Ottawa: Solicitor General of Canada.

3 Lewis, S. (2016) Therapeutic Correctional Relationships: Theory, Research and Practice. London: Routledge.

Frank Porporino has a Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology with a career in corrections spanning more than 40 years as a front-line practitioner, senior manager, researcher, educator, trainer, and consultant. His public service career spanned 22 years with the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC), ending the public sector phase of his career as Director of Strategic Planning and Director General of Research and Development. Frank co-founded T3 Associates Training and Consulting Inc. in 1993 in order to provide research-based training and technical assistance in effective practice to correctional jurisdictions and social service agencies internationally. Internationally, he has worked in more than 20 countries, including in the UK, Europe and the Scandinavian countries, Australia and New Zealand, and most recently in extensive engagements with the Singapore Ministry of Youth and Family Services, the Barbados Prison Service in the Caribbean, the Irish Prison Service, and a lengthy and ongoing service as consultant to the Namibian Correctional Service in Africa. He is currently Past President of IACFP and Editor of Managing Corrections, International Corrections and Prison Association.