A new article in Criminal Justice and Behavior focuses on the use of a dynamic security model, which has grown in interest and application worldwide. For the article, researchers focused on the use of the dynamic security model in the Norwegian Correctional Service (NCS) and the perspective of incarcerated individuals on whether or not it has been effective in creating a rehabilitative environment. Here, we summarize the purpose, design, and results of the study, as well as recommendations for future research.

What Is Dynamic Security?

Dynamic security focuses on training correctional officers to use relationship building and open communication with incarcerated individuals to create an environment conducive to rehabilitation, reduce prison-based violence, and facilitate positive change.

The most well-known and oft-cited use of this model comes from the NCS. Halden prison has been featured numerous times in media, research, and reports. Research has demonstrated that "Officers who engage in ongoing, meaningful communication, show respect toward those they supervise, and practice fair and flexible use of their authority are more likely to be perceived as legitimate sources of authority within the prison."

The combination of media notoriety and evidence-based outcomes has led to more prisons choosing to train correctional officers in the dynamic security model.

Purpose of Study

Although "relationship building and communication are generally considered central to dynamic security, there are no established standards for a dynamic security model of correctional supervision." Even though more correctional officers across the world are being trained in this model, practices and application can and do vary widely among facilities.

The purpose of this study was to:

- Examine the differences between dynamic security training and static security training;

- Determine the model's efficacy at establishing "the legitimacy of officers;"

- Gather first-hand perspectives from incarcerated individuals on their experiences with dynamic security to determine "what works;" and

- Identify potential barriers to effective officer participation in the dynamic security model.

Static vs Dynamic Security

Static security physical and procedural methods aim to maintain safety within a correctional facility. Examples of static security include locks, cameras, and prison layout, as well as enforcement of rules, adherence to daily schedules, and "maintaining order."

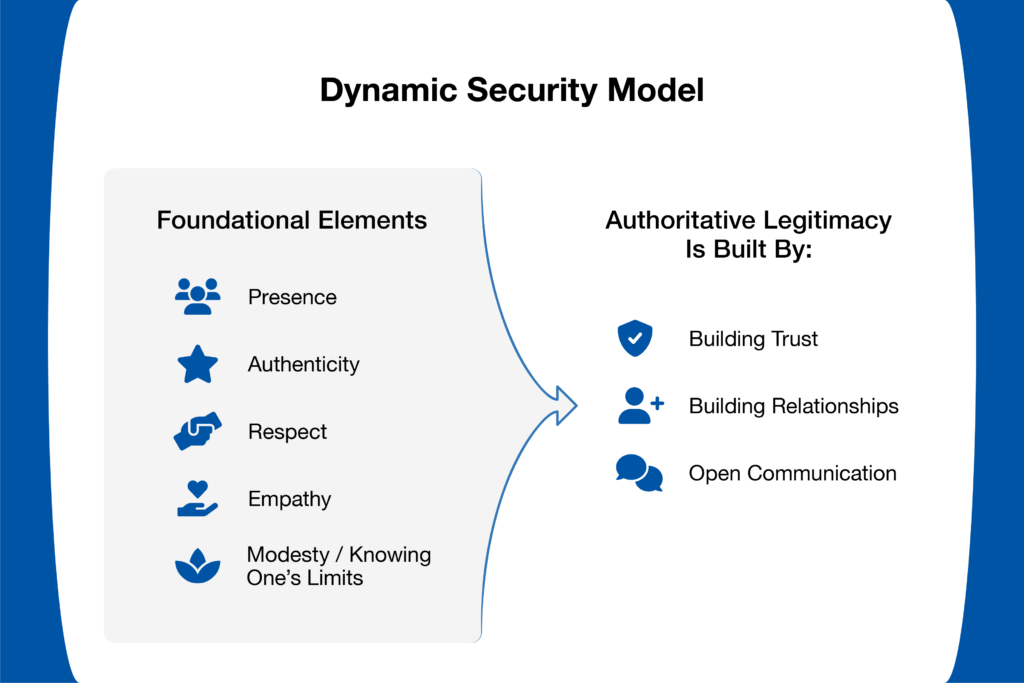

Static security is considered to be "essential to the safety within a prison;" however, dynamic security offers an additional approach to maintaining control through relationships correctional officers build with incarcerated individuals with the following foundational elements:

- Presence;

- Authenticity;

- Respect;

- Empathy; and

- Modesty (in this case, knowing one's limits).

According to the Council of Europe, the dynamic security model "is a proactive method of identifying and addressing threats to security that requires officers to be present, interact, and engage in meaningful activities with those incarcerated."

In addition the use of this model is meant to build a sense of legitimacy and perceived institutional authority for correctional officers by establishing trust, building relationships, and maintaining open communication.

Use in Norway

Of the 58 prisons run by the NCS, approximately 70% are considered high-security facilities. In accordance with their cultural values, "officers in Norway are trained to understand prisons as a place to maintain safety and security as well as a space in which rehabilitation takes place."

Correctional officers in Norway must complete two years of formal training, and "are expected to perform security, intervention, and rehabilitation-oriented duties" once they are placed in a facility. Correctional officers engage in both formal and information communication with incarcerated individuals and are assigned two to three individuals with whom they serve as the main point of contact. In their role as "contact officer," they help their assignees develop a "future plan" that includes both rehabilitative and treatment goals that will aid in rehabilitation.

Use in the U.S.

AMEND, a nonprofit organization located in the United States, has facilitated the training of U.S. correctional officers through travel to Norway to observe dynamic security practices. Those who have participated in this training and adopted the dynamic security model have reported positive results. For example:

- The North Dakota Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation saw reduced recidivism, a decrease in behavioral unit placements, and a reduction in the need for segregated housing.

- Correctional officers at the Oregon Department of Corrections reported a decrease in violent incidents, reduction in the need for physical force, and increased work satisfaction.

Although the positive results reported in these two locations are encouraging, no studies yet exist that examine 1) the therapeutic benefit of the dynamic security model or 2) the perceptions of incarcerated individuals on the benefits (or lack thereof) of using this model.

Study Design

The authors conducted their research at the Halden Fengsel (prison) over a period of three weeks in summer 2017. Information from participants was gathered via a confidential questionnaire consisting of 22 questions, most of which used a Likert-type scale. Of the 121 distributed, 81 were completed, representing a response rate of 67%.

Of the 81 participants who completed the questionnaire, 47 agreed to also participate in a semi-structured interview conducted by the research team in the language of their preference (e.g., English or Norwegian). Answers to both the questionnaire and collected during the interviews were analyzed using a two-coded process to identify themes that could be added to the quantitative data.

Key Findings

"Findings from the questionnaire and interview data indicate that the Halden officers have been generally successful at attaining authoritative legitimacy through the implementation of dynamic security practices."

Yet, incarcerated individuals at Halden did not attribute "therapeutic legitimacy" to the correctional officers and "did not see them as part of the treatment or rehabilitative process."

Additional insights included:

- Most respondents reported a "preference for relationships with officers who made time for communication and engagement."

- Officers who were described as using "a defensive, security orientation" were seen as more impersonal, which led to a perception of less "authoritative legitimacy."

- Both words and demonstrations of support were identified by participants as important to them, and correlated with their perceptions that they were both supported and understood by their contact officers.

- "Discretion" was another distinguishing factor among elements considered most important by respondents. "There was a clear preference for officers who balanced their use of authority and rule enforcement with flexibility and compassion."

- Participants felt frustrated by officers who always did things "by the book" or who used threats of discipline or coercion tactics to secure compliance.

- "Respect was often described as a dynamic, transactional process where they would show respect toward an officer as long as a similar level of respect was demonstrated toward them."

- Participants identified respect as follow through (or keeping one's word) with regard to their requests. This is in contrast to what training often focuses on as a form of respect, such as using a friendly tone or courteous language.

Although the study results indicated that the dynamic security model has been successful in establishing authoritative legitimacy, the results also indicated that participants largely rejected the idea of correctional officers being part of the therapeutic process.

Barriers identified with regard to officers having "therapeutic legitimacy" included:

- Correctional officers are viewed as a part of the punitive design of the institution. Their focus on "security and control" is – in the eyes of incarcerated individuals – in direct opposition to being able to have "an active role within the treatment process" or engage in rehabilitation.

- Participants indicated "they would not share more sensitive details about their lives with their contact officers."

- Respondents indicated they distrusted the motives of the correctional officers during conversation, stating they believed officers were often "initiating conversations not as a genuine desire to build relationships but as a security tactic to gather intelligence."

- Prison cultural norms, such as not trusting or involving those in authority, often influenced whether or not incarcerated individuals would discuss conflicts or problem behaviors with officers.

- The "no snitching" rule also influenced the participants' unwillingness to bring up "unit-based conflicts" with officers, including their contact officer.

Recommendations and Next Steps

Findings indicated the dynamic security model has been successful in establishing the authoritative legitimacy of correctional officers at Halden, yielding a reduction in conflict and non-compliance. Yet, the inability of officers to establish therapeutic legitimacy does not uphold the prison's intended goals of supporting rehabilitation and the treatment process.

The role of correctional officers necessitates a focus on security and rule enforcement. This leads to skepticism on the part of those who are incarcerated and a sense of mistrust that impedes therapeutically-oriented relationship building. "This raises important questions about whether officers can realistically participate in the rehabilitative process while also maintaining their role as the enforcer of rules and punishment, which can include the use of coercion and physical force."

This does not mean officers are incapable of establishing therapeutic legitimacy, but instead that their role as an authority feature makes it impossible to be successful in both roles. For example:

"It could be argued that the more authoritative legitimacy an officer gains within their role as a rule enforcer, the less likely it is that they will be accepted by incarcerated individuals as having legitimacy in the rehabilitative process. The forms of communication and officer-incarcerated interactions that promote compliance without the use of coercion may be insufficient or even detrimental to the rapport-building and trust that is needed in more therapeutic relationships. In addition, the role of officers in enacting sanctions for non-compliance or rule violations makes it less likely that incarcerated individuals will “confide” in an officer about a conflict they are having with another individual or their engagement in prohibited behaviors."

Additional considerations cited by the authors for those interested in using the dynamic security model included:

- Scaling the dynamic security model from a prison with 250 incarcerated individuals to one with several hundreds or thousands creates both "logistical and resource barriers." This must be carefully considered by countries with larger prison populations, such as the United States or United Kingdom.

- For those facilities with larger populations, application of the model may be best directed toward "general housing units" or "specialized units containing smaller populations."

- "Staff buy-in is essential" for the model to function effectively.

- "Expectations of dynamic security’s ability to promote rehabilitation or treatment goals in addition to increasing control within housing units should be tempered with acknowledgment of the pressure for officers and incarcerated individuals to adhere to long-standing prison culture norms."

All research for NCS's dynamic security model is available through the University College of the Norwegian Correctional Service.

* References available upon request.

Source: Kilmer, A., Abdel-Salam, S., & Silver, I. A. (2023). “The Uniform’s in the Way”: Navigating the Tension Between Security and Therapeutic Roles in a Rehabilitation-Focused Prison in Norway. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 50(4), 521-540.