New research has been published in Criminal Justice and Behavior examining the efficacy of personality disorder treatment for incarcerated individuals. The study—conducted in the United Kingdom by Nicholas Blagden, Jacquie Evans, Lloyd Gould, Naomi Murphy, Laura Hamilton, Chloe Tolley, and Kyra Wardle—identified three key themes related to the impact and experience of personality disorder treatment received by those during incarceration in a high-security facility. Here, we summarize the research background, purpose, method and design, findings, and considerations for future studies.

The full article entitled, "The People Who Leave Here Are Not the People Who Arrived.” A Qualitative Analysis of the Therapeutic Process and Identity Transition in the Offender Personality Disorder Pathway, is available here.

Background for the Study

"While it has long been recognized that the function of prison should include rehabilitation … individuals with personality disorder are often construed as difficult to treat, and sometimes even “untreatable.'"

In 1999, the UK government established a program intended to address the issue of high-risk individuals with severe personality disorder being funneled into prisons, rather than psychiatric facilities. This program, named Dangerous & Severe Personality Disorder (DSPD) pilot service, was decommissioned in 2011, despite having "some success."

A new initiative was begun in 2011, named the Offender Personality Disorder (OPD) pathway, which "aimed to provide interventions for a greater number of individuals [by] incorporating lessons learnt from the DSPD pilots and guidance from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence."

The OPD Pathway combines the efforts of Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service and National Health Service (NHS) England with the goals of:

"(1) reducing serious violent and sexual reoffending, (2) improving psychological health, wellbeing, prosocial behavior and relational outcomes, (3) improving competence, confidence and attitudes of staff, and (4) increasing efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and quality of services."

While the prevalence of personality disorder among the general population is only 4-11%, the average for incarcerated males is much higher, reaching 60–77%. Yet, the individuals who are often labeled as "high-risk" and/or "personality disordered" are quite varied and "rarely fit neatly into one diagnostic category or treatment pathway."

These individuals typically have comorbidities, such as developmental trauma, substance use disorders, or other mental illnesses. Many were exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which - for those with personality disorder - are "associated with increased prevalence of several health risk behaviors, including engagement in substance use, criminal, and risky sexual behavior."

Purpose

"The high prevalence of people with complex mental health presentations in OPD services, coupled with higher rates of recidivism, has long been a priority for researchers, clinicians, and policymakers to understand and implement effective forensic interventions."

Individuals with personality disorder, regardless of setting, can experience "an impaired quality of life, high amounts of stress, a reduced life expectancy, and high rates of suicide." Because a structured narrative of self is essential to effective functioning of the personality within an individual, the OPD pathway focuses on developing "of a cohesive self-structure, while recognizing the disruptive impact of ACEs."

Determining the efficacy of treatment using the OPD pathway has been prioritized in prior research, particularly with regard to reduction of recidivism; however, no studies have focused on the process or experience from the point of view of those who have completed the full five-year treatment protocol. Thus,

"The current study aims to explore the lived experience of a group of adult males who completed the Fens Unit intervention, and to understand the impact of treatment on their identity, their relationships with others, to explore the environment of therapy, and the process of therapeutic intervention."

Method and Design

Participants were recruited for the study from a high-security prison located in England and Wales. Of the 49 who were determined eligible for the study, 24 agreed to participate. All took part in the Fens OPD pathway and agreed to join 10 focus groups within 2 weeks of treatment. The focus group examined:

- Their experience of the treatment;

- The impact of the OPD pathway on their sense of self;

- Their relationships with other patients in the program and therapists;

- Their experience of the therapy environment; and

- Whether there was anything they would change within the treatment process.

Researchers collected data from February 2010 to January 2020 for the men completing treatment, who ranged in age from 26 to 64 and were convicted for sexual and/or violent crimes.

Thematic analysis was used as "a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns and themes within a dataset." Qualitative data collected during the focus groups was read, coded, and then used to generate themes.

Findings

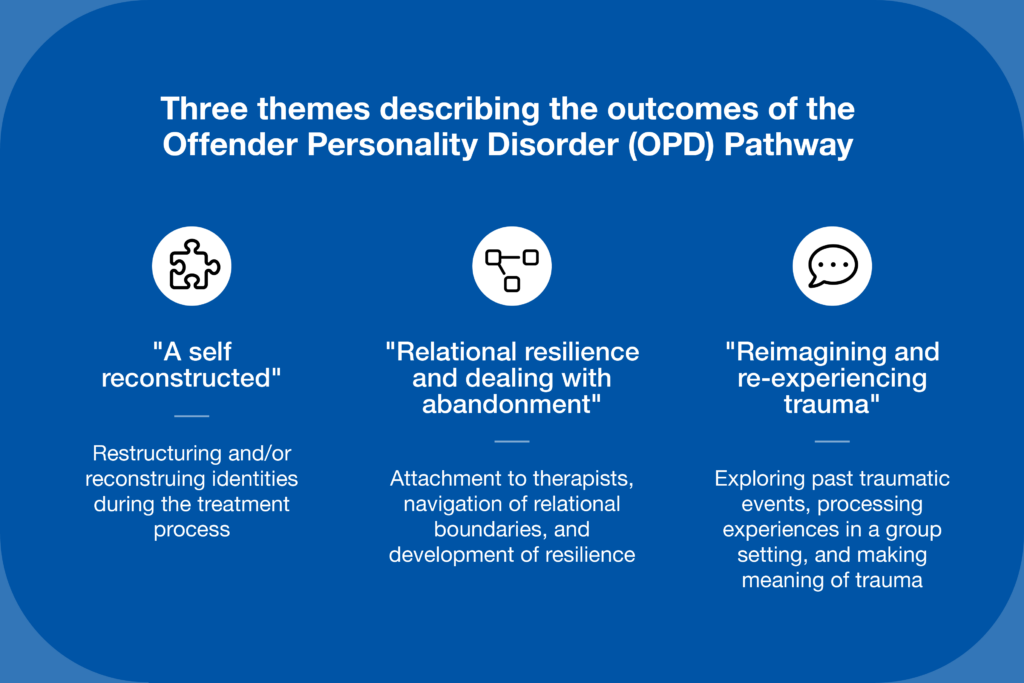

Upon analysis, the authors identified "three superordinate themes that captured the impact and experience of the therapeutic process for individuals with personality disorder." These were:

- "A self reconstructed," which relates to the men's experience of restructuring and/or reconstruing their identities during the treatment process;

- "Relational resilience and dealing with abandonment,” which involves the men's attachment to therapists, their navigation of relational boundaries, and the development of resilience; and

- “Reimagining and re-experiencing trauma,” which connected to how the men explored their past traumatic events, processed those experiences in a group setting, and ultimately reconciled those realities—enabling them to make meaning of and reconstrue their trauma.

Responses Related to Theme 1

Participants communicated the following during the focus groups:

- Despite a "Hell of a lot of talking; and a hell of a lot of soul searching," the men found the process to be both meaningful and powerful - ultimately yielding a shift in identity. One participant summed this up by saying that the "people who leave here are not the people who arrived.”

- The treatment helped the men reshape their identities into something that made them feel more positive. One participant said "one of my plans was to completely clear out my locker of all the abuse in my life and I’ve done it, so I feel proud of myself."

- Participants had to be open to and feel worthy of change, exemplified in this response: "You gotta have self worth though, and the self worth should override the self pity within what you do and how you look at the things you’ve seen."

- The overall efficacy of the program was confirmed by the men, many of whom shared significant stories of change: "Has it made me a better person after the five years? Absolutely. Has it given me more insight into my lifestyle and so on? Yes, absolutely, I’ve gained massive amounts from it."

Responses Related to Theme 2

Within the focus groups, the men were also able to identify that they had experienced a powerful bond with their therapist, which helped them examine past relational patterns and consider their approach to relationship building. For example, one man reported: "I was rebelling against my mother in a way, with my therapist."

This made changes in staffing particularly important, with one man noting:

Because we’re building relationships with these people then if they move on just like that, then what’s the point? So, it was times like that with, with staff that we really, kinda, struggle within therapy. With, do I carry on? Do I just not commit as much? Do I not try and build relationships while I’m doing this therapy?"

Which suggests "transference from previously abandoned and damaged relationships impacts on patients’ therapeutic journeys" and that continuity can have a therapeutic effect for those in the OPD pathway.

Not all participants found staff changes upsetting, however, with some describing those changes as beneficial to their growth: "I think changes in staff takes you out of your comfort zone and that can make you a stronger person."

Responses Related to Theme 3

When considering their experience with trauma and the impact of processing those events with a group in order to reconcile their past, the men reported:

- The therapeutic process enabled them to reframe their experiences and gain a new perspective due to the group setting. One participant shared: "That small group was the most I have ever been open and honest with anyone in my, my entire life, and the longest I’ve ever spent within a group of people."

- Dealing with histories of abuse - often a precursor to personality disorder - could lead to resistance: "Cause sometimes you think, it’s quite hard, and, difficult to hear and, to cope with afterwards."

- The process of sharing trauma to make meaning of painful events (and reconstruct a sense of self) and the process of reliving trauma through hearing of others' experiences (which can cause psychological distress in the moment) were ultimately seen to support the participants' positive growth. It should be noted, however, that three of the five years for the OPD pathway intervention were spent working on the men's trauma.

Concluding Thoughts

"This research highlighted that crucial to an individual’s progression through treatment intervention was the ability to reflect upon their sense of self and past experiences, to shift narratives from disorder to order and gain new understanding of self and their trauma from therapeutic and other group member relationships."

The authors noted it would be beneficial to examine a broader range of participants across geographical and facility location. It might also be useful to examine the experiences of those who have dropped out of treatment before completion.

This study was the first to analyze the efficacy of the five-year OPD pathway treatment model using qualitative data. Because this study was holistically focused, future research could be conducted on specific elements that make up the totality of the OPD pathway program.

* References available upon request.