The January 2025 issue of Criminal Justice and Behavior has published a new study of the Offender Personality Disorder (OPD) Pathway co-authored by Manuela Jarrett, Julie Trebilcock, Tim Weaver, Andrew Forrester, Colin D. Campbell, Mizanur Khondoker, George Vamvakas, Barbara Barrett, and Paul A. Moran. The OPD Pathway is a network of services across prison, health and community settings in England and Wales developed by His Majesty’s Prison & Probation Service (HMPPS) and National Health Service in the United Kingdom. It was designed to provide mental health support for incarcerated individuals with personality disorders. The study was a component of a national review of the OPD Pathway that specifically solicited qualitative responses from a pool of subjects to learn their responses to the program services and the impact on their mental health. The researchers found that while the participants had overall positive views of the Pathway services, frequent staff turnover and lack of clarity about the roles of individual administrators led to feelings of uncertainty and mistrust of the program.

BACKGROUND

The OPD Pathway was first established as a successor to the Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder (DSPD) Program that had been instituted in 2002. Several controversies about the DSPD’s methodology and effectiveness led to the program being decommissioned in 2011, with the funding being redirected towards the more therapeutic approach of the OPD Pathway, which is overseen by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and National Health Service (NHS). Several studies have indicated that criminal justice settings in many countries (ie, prisons and probationary supervision) show a high prevalence of individuals with personality disorders, ranging from 50-70% compared to a range of 4-11% in the general population. In stark contrast to DSPD’s philosophy of “preventive detention” – which aimed to identify individuals at high risk for committing violent crimes and restrain them in advance – the OPD Pathway focuses on those who have already been tried and sentenced with a multi-tiered set of goals:

- Reduce the risk of serious sexual and/or violent re-offending

- Improve the overall psychological well-being of OPD Pathway participants

- Increase competence and confidence of staff involved in the program

- Increase cost-effectiveness and efficiency of Pathway services

Services are provided across a broad range of environments that include varying security levels of prisons as well as within secure hospitals and community outpatient settings. Within prisons, some nontreatment settings are also designated as Psychologically Informed Planned Environments (PIPEs) where psychologists provide clinical supervision to unit staff to facilitate therapeutic relationships and services. Eligibility for services within the OPD Pathway are based on the following criteria:

- Individual has been assessed to show high likelihood of violent or sexual re-offending and high risk of committing serious harm to others

- Individual shows a high likelihood – if not a specific diagnosis – of a personality disorder

- There is a “clinically justifiable link” between the personality disorder and the risk of re-offense

Potential participants in the OPD Pathway are reviewed on a case-by-case basis by NHS psychologists and Offender Managers (OMs) to determine level of severity across the above criteria. In addition to deciding whether or not an individual qualifies for the OPD Pathway, a determination will also be made regarding which services and interventions are most appropriate throughout their sentence.

The UK government conducted its national evaluation of the OPD Pathway for male prisoners between 2014 and 2018, using a mixed-methods design that combined quantitative data with interviews from program participants and staff. They also commissioned more focused studies on the effectiveness of the Pathway services within the city of London, the nation of Wales, and among female prisoners. The quantitative results of the national evaluation, released in 2022, seemed to show minimal difference between the outcomes of Pathway participants and those who were not involved in the program, although there are concerns that there has not been enough time allocated to follow-up for further analysis and evidence gathering.

The researchers conducting this summarized study have elected a solely qualitative approach that inquires about the experiences of Pathway participants and whether they felt the services had positively impacted their mental wellbeing. This data offers opportunities for OPD Pathway facilitators to adjust their program based on relevant feedback.

METHODOLOGY

The researchers sought to assemble a pool of interview subjects from an array of Pathway service sites to ensure geographic diversity across London and Wales and include as many different types of services as possible.

Participant Locations

The sites chosen for the study were:

- Four prison-based personality disorder treatment units – two from Category A (highest security) and one each from Categories B and C (lower security) – that offered both individual and group therapy

- One Democratic Therapeutic Community (DTC), which offers both psychotherapy and a community-based model of engagement

- One Provision PIPE – in which prisoners reside while receiving treatment in another location – in a Category B prison

- Three Progression PIPEs – in which participants who have completed an OPD program are allowed to practice their learned skills – in one Category designation each

- One NHS community-based outpatient personality disorder treatment unit

- Two Approved Premises PIPEs, which are residential buildings in public communities where released individuals can receive support

- Four Local Delivery Units, where participants receive case consultation

These 16 settings were located within 5 National Prison Service regions (North East, North West, Midlands, South West, and South East) that have since been split further into 11 regions.

Study Participant Characteristics

The researchers asked the lead clinicians in each service to identify two people who had been in the Pathway program for at least six months and were open to speaking about their experiences. Subjects needed to be 21 years of age or older and be fluent in English. This method helped produce a final pool of 36 participants, ranging from 23 to 58 years of age. Other key characteristics of the sample included:

- The overwhelming majority of participants identified as White British (33 of 36)

- Nearly half (15 of 36) were serving life sentences

- Over a quarter (10 of 36) were serving determinate sentences of 2-14 years

- One of the participants was serving a 1-year Community Order

- The offenses committed by the participants included robbery, arson, sexual offenses, grievous bodily harm, and murder

- On average, the participants had served 9.2 years of their sentences and had been involved in OPD Pathway Services for 14.5 months

The participants described similar life and mental health experiences besides their personality disorder, including:

- Psychosis

- Anxiety

- Depression

- PTSD

- Self-harm and attempted suicide

- Abuse of alcohol and substances

- Childhood adversity and abuse

- Repeated contact with law enforcement and prison or community sentences

Other details reported by the study participants included their relative experiences of incarceration; while some described ease in serving their sentences, most described patterns of conflict with staff and other prisoners, and of behaviors that underlined overall “problems with authority.” These patterns led to consequences such as regular assignment to segregation units, as well as additional time on their sentences or inability to achieve parole. Some of these also expressed unsuccessful attempts to engage with treatment prior to being qualified for OPD Pathway.

KEY FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATIONS

The data collected from the surveys was organized into two key themes:

- Experiences of the OPD Pathway as illustrated by relationships with program staff in both secure and probationary environments.

- The effect of these relationships on psychological wellbeing.

Staff Relationships

Within the first theme, participants generally indicated positive perceptions of Pathway services staff, including descriptions that they were “approachable, kind and respectful and offering a high level of support.” While prison officers were also perceived as building positive and therapeutic rapport, some Pathway participants noted the tension in these officers also having to maintain security standards. One prisoner specifically pointed out that it was difficult to absorb therapeutic feedback from an officer who had earlier in the day had to administer a disciplinary action:

“So you’re not going to listen to what they are going to be saying because you’re thinking ‘well, you stitched me up this morning and now you’re trying to teach me the laws on life…how to be a better person or whatever, when you’re not like, I don’t think you’re like that yourself, so why are you preaching to me?” (O2, Prison PD Treatment Unit)

There was also a mix of perception around clinical treatment staff, with some respondents reporting that these mental health professionals were “attuned” to the emotions and needs of Pathway users but also feeling concern about their power to manipulate the prisoners’ tenure in the criminal justice system through their recommendations. The majority of study participants nonetheless commented positively about the transparency, empathy, and openness of these staff members.

Similar positive perceptions of staff in community probation settings were reported – the study participants said that their interactions with these staff members left them feeling listened to and respected. They also described a renewed sense of agency in their decision-making routines and management of the risk factors that could lead to re-offending. Rather than issuing demands, community-based Pathway staff would offer feedback and be open to suggestions, which encouraged the Pathway service user to be more honest and take greater responsibility for their progress.

Despite these positive aspects, participants did also make the particular observation that staff turnover was a detriment to their process within the Pathway. A lack of continuity in who was helping to treat them was frustrating and unsettling. Program participants often had to share personal information repeatedly – in effect, starting over – which made them less likely to invest in the relationships at all.

Psychological Wellbeing

Pathway services and the relationships that participants established within the program led to a number of positive effects on mental health and wellbeing. For example, many of the study participants discussed feelings of safety within the Pathway locations and programs in stark contrast to their feelings of fear in normal prison environments. This feeling of security, in turn, gave Pathway participants the ability to be open about their feelings and do the work required of treatment instead of persistently worrying about unpredictable violence.

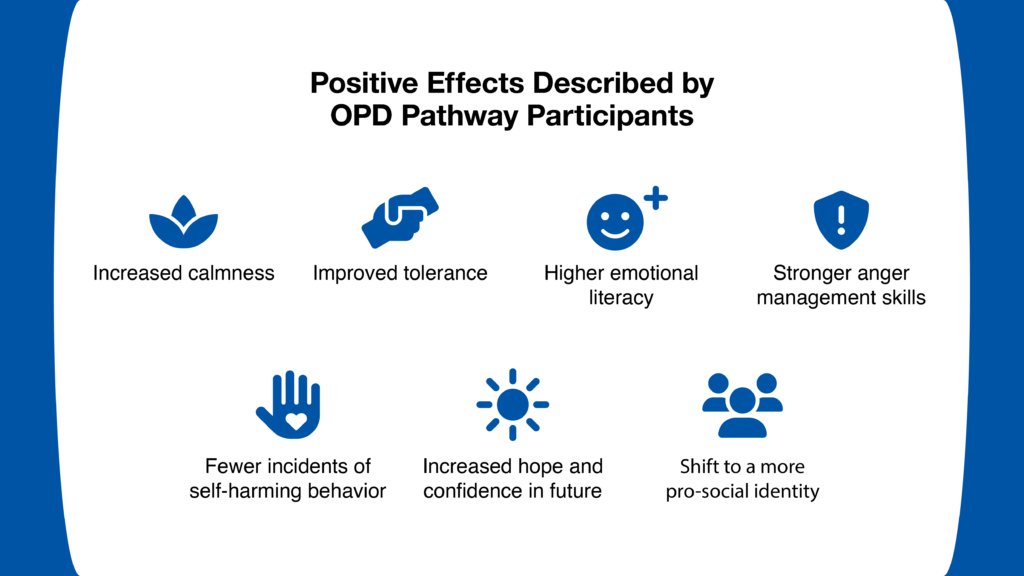

Participants also described reduced levels of “emotional turmoil,” which led to positive effects such as:

- Improved calmness and ability to tolerate stressful situations

- Higher emotional literacy

- Better anger management skills and fewer incidents of anger

- Fewer instances of self-harm

They also felt an increased sense of hope and confidence in their future, and a shift in how they identified themselves – many who had internalized the idea that they were a “hardened criminal,” for example, began to develop an identity more akin to positive social relationships and interactions, including with their families.

CONCLUSIONS

The researchers note that despite several of the strengths of their study – including a diversity of perspectives across Pathway environments and the use of case summaries to record comprehensive data – there were also a number of limitations. The sample pool was predominantly White, which means there is little information about how Pathway programs are perceived by other races or ethnicities. The sample was also a “convenience sample” of participants selected by program psychologists, which means there may have been a bias towards more cooperative and positive responses. The study also cannot conclude on its own if positive response to Pathway programs has led to reduced incidences of re-offending.

These limitations notwithstanding, the researchers feel that the qualitative data received from the surveys indicates that the OPD Pathway offers clear benefits to its participants. The overall response to the program is positive and has led to improvements in behavior and psychological wellbeing. The relational approach to Pathway services has seemed to offer a sense of safety that helps develop more pro-social identity and hope for the future. The structure of the services has also encouraged greater agency among the participants. However, many participants also noted that staff turnover is a significant hindrance to the effectiveness of the program, and the researchers believe that addressing this issue is crucial to the continued success of the OPD Pathway.

"Study participants said that their interactions with [community-based staff] left them feeling listened to and respected. They also described a renewed sense of agency in their decision-making routines and management of the risk factors that could lead to re-offending."