A study by Pia Puolakka and Maarit Suomela–published in Edition #16 - 2023 of Advancing Corrections Journal–takes a look at how the Doris Smart Prison Project has been utilized within the Finnish prison system to increase inmates’ access to digital resources during their incarceration. As many social and professional aspects of modern society have become increasingly digital, deprivation of such access among prisoners is causing greater marginalization. The initiative to provide improved digital rights in Finnish prisons therefore aims to improve prisoners’ basic human rights, supporting their rehabilitation within prison and their reintegration in communities after their sentence has been completed.

Background and Research Purposes

Although many nations have instituted laws regarding the concept of digital rights, in 2015 Finland became unique in legally extending such rights to incarcerated people through a revision of its Imprisonment and Remand Imprisonment Acts. Within the new provisions of the Acts, prisoners were entitled to receive permission for:

- Internet use for “subsistence, or attendance to work-related, educational, judicial, social or housing matters”

- Communication via “video connection or other suitable technical means” with family, relatives, or legal counsel

- Sending and receiving email messages for “subsistence, or attendance to work-related, educational, judicial, social or housing matters,” or to communicate with legal counsel for their judicial matters

Since the new legislation was enacted, The Prison and Probation Service of Finland has taken steps to fulfill these requirements, such as the installation of joint-use laptop workstations in all prisons in 2017–a system that is due to be replaced by the allowance of personal cell devices, which better enable prisoners to meet their needs for digital services. In 2021, the country also established Hämeenlinna women’s prison–the only closed-unit women’s prison in Finland–as the first Smart Prison, envisioned as a “a learning environment for a life without crime.” A key element of that vision was that access to digital services would enable rehabilitation and reintegration by enhancing the digital skills required to succeed in Finnish society’s educational and vocational structures. This access was provided via the Doris system, which has now also been instituted within two closed-unit men’s prisons as of 2023.

Doris is provided through permitted use of personal cell devices, and allows for the following services:

- Messages, requests, and video calls to prison staff, prison healthcare services, and authorities or cooperation partners such as NGOs, the Social Insurance Office, etc.

- Video calls and e-mail to communicate with family or other close contacts, legal counsel, or other officials involved in their case

- Restricted access to the Internet via a whitelist of several hundred websites, such as Moodle (for online studies) an online shopping site, and other selected websites that support rehabilitation and management of daily affairs, such as online mental health programs and self-help materials

Whitelisted websites, which have also been available on the joint workstations in other closed prisons, have been security checked and were curated through feedback from prison staff, senior specialists, and people in custody.

After two-and-a-half years of development and refinement of the Doris system within Hämeenlinna women’s prison, the researchers sought to gather opinions from the prisoners to learn if the current situation was “enabling rehabilitation and human rights during incarceration.”

“Lack of access to digital devices and digital skills leads to digital marginalization and digital divide – the marginalized gets even more marginalized in a digital society. Digital skills are the new literacy skills, and we should be able to support prisoners in acquiring more of both…justice involved individuals’ human rights are in many ways dependent on the digital rights we can provide them.”

Methodology

The study gathered data by administering an electronic questionnaire through Doris to 100 inmates within the Hämeenlinna women’s prison throughout July and August 2023. The survey used a Likert model that provided 18 statements, then asked respondents to articulate their agreement or disagreement on a 1-5 scale (ie, 1=totally disagree; 5=totally agree): Examples of these statements included:

- Doris provides me services that improve my rehabilitation during incarceration.

- Via Doris I can write my homework, notes, and paperwork.

- Via Doris I can take care of affairs considering my release from prison.

- Via Doris I can keep better contact to my close ones.

- Via Doris I can keep better contact to my children.

- Via Doris I can keep contact to organizations and civil services that help me with my situation.

- When I am alone in the cell, I can find meaningful activities via Doris (Internet connection, material bank, other utility programs).

- I think Doris helps me to take care of my rights and human rights during my incarceration.

The researchers note that a subject pool composed solely of women within the Finnish prison is limited, and that prior studies have shown “many risks and special questions apply especially to women in custody compared to males, like heightened need for mental health services and extensive trauma history.” Nonetheless, the study focused solely on subjects within Hämeenlinna because the prison had adopted Doris in 2021, and could offer more experienced feedback than the men’s prisons that began using Doris in 2023. Future research will likely include these populations of male prisoners, as well as surveys of prisoners from other distinct groups, such as younger or elderly inmates, those with non-binary gender identities, and those from different ethnic backgrounds.

“Keeping prison conditions and inside prison (digital) connections equal to the conditions and connections outside is of vital importance and reflects the principle of normality – one of the key legal principles in Finnish prison service.”

Findings and Interpretations

The researchers only received 19 responses out of 100 surveys sent–a lower number that aligns with previous results from other feedback surveys sent through Doris. This 19% response rate may be due to different factors, including the fact that foreign inmates without fluency in Finnish were unable to engage the survey. Within the received responses, the researchers noted several positive insights, including:

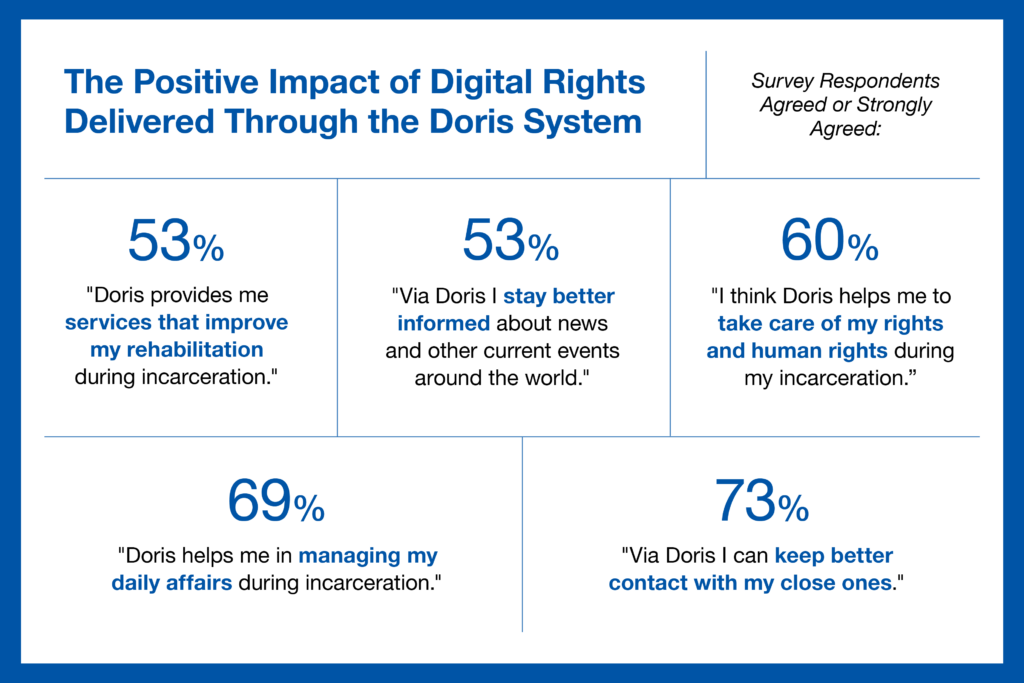

- A majority of respondents agreed or strongly agreed Doris provided services that improved their rehabilitation (53%), including services that helped with studying and homework (56%) or those that helped them manage daily matters (69%).

- Higher levels of agreement or strong agreement on questions related to the use of Doris to keep in touch with children and other close contacts (62-73%).

- Higher levels of agreement or strong agreement on questions related to the use of Doris to stay informed about the world or engage in other meaningful activities (53-60%).

- A high level of agreement or strong agreement (60%) with the statement “I think Doris helps me to take care of my rights and human rights during my incarceration.”

Statements that showed high levels of disagreement related primarily to taking care of social matters or being able to contact officials who were handling their individual case. The results also indicated a high level of indifference or inability to state a strong opinion (neither agree nor disagree) regarding the capacity to use Doris for activities such as engaging with supportive organizations or services, or handling matters related to their eventual release. A majority (47%) could not express whether Doris would reduce their risk of recidivism, which may more accurately reflect that release from prison is not a current concern, since most respondents indicated they were taking advantage of those services designed to prevent a return to incarceration.

Conclusions

Based on this research and previous surveys of both prison staff and inmates, the researchers believe that further expansion of the Doris system and Smart Prison model to include all Finnish closed-unit prisons would produce significant benefits. Several previous studies have also shown that digitalization “promotes social skills of people in custody, self-esteem, rehabilitation and their reintegration into society.” The results of this study indicate that within the first established Smart Prison supported by Doris, inmates are recognizing and taking advantage of their digital rights to stay aligned with the digitalization of modern society. This, in turn, enhances their human rights and provides a stronger foundation for their rehabilitation and reintegration after imprisonment ends.