In a recent study that builds upon several prior studies, researchers Ryan Coulling, Matthew S. Johnston, and Rosemary Ricciardelli examine the myriad factors that affect the mental health and well-being of workers in the Canadian correctional system. The new study – published in the January 22, 2024 issue of Frontiers in Psychology – takes a qualitative approach to analyzing mental health in corrections by focusing on the comments that participants wrote in response to an open-ended question at the end of a comprehensive mental health survey. Through this data, the researchers identified several themes that provide a more thorough picture of the challenges in correctional work.

Background and Research Purposes

A number of studies have already illustrated that the particular stresses of working in correctional facilities can lead to serious mental health issues. Research has identified each of the below as incidents that staff may be exposed to as part of routine operational duties, all of which can be categorized as potentially psychologically traumatic events (PPTE):

- Assault of correctional staff

- Verbal aggression against correctional staff

- Witnessing violence between prisoners

- Witnessing prisoner self-harm, including suicidal behaviors or actions

(Sources: McKendy et al., 2021; Boudoukha et al., 2011; Viotti, 2016; Barry, 2017; Walker et al., 2017; Lerman et al., 2022)

In addition to operational factors, studies also identified organizational stressors such as conflict between management and coworkers, and those involving employment conditions. These stressors included:

- Verbal assault (harassment, bullying, discrimination)

- Physical assault

- Insufficient or absent managerial response to staff concerns

- Workload / shift conditions

- Labor shortages

- Contractual employment

- Wages and benefits

(Sources: McKendy et al., 2021; McKendy and Ricciardelli, 2022; Triplett et al., 1996; Keinan and Malach-Pines, 2007; Swenson et al., 2008; Morse et al., 2011; Brower, 2013; Ricciardelli et al., 2020.)

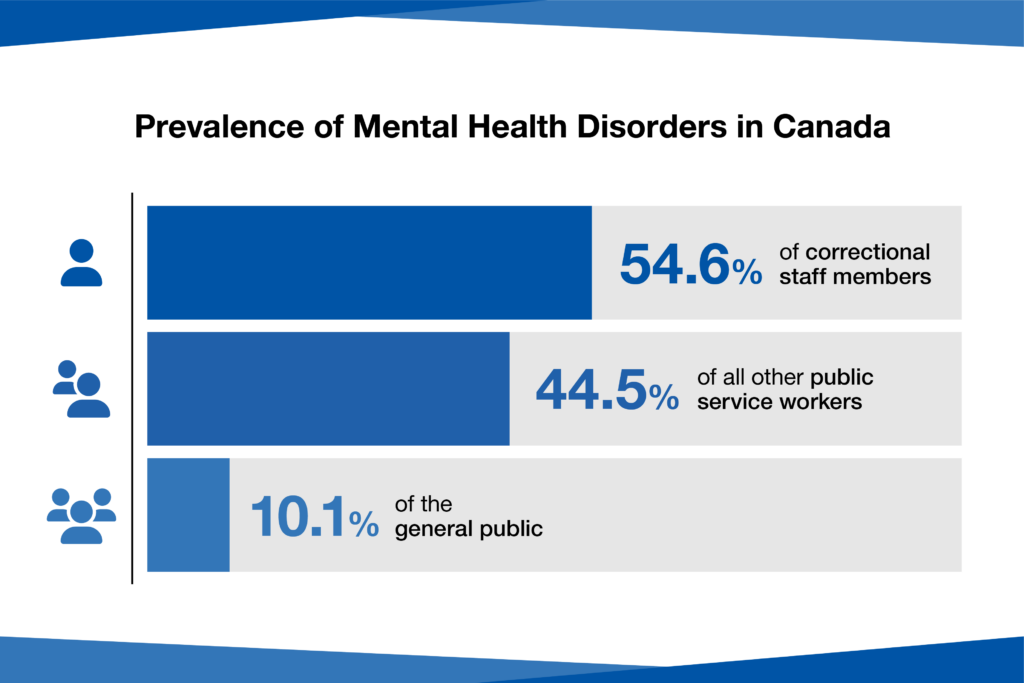

Additional research (Carleton et al., 2018, 2022; Ricciardelli et al., 2018) indicated that well over half of correctional workers – 54.6% – presented signs of experiencing mental health disorders, which was a much higher prevalence than was found in other public safety workers (44.5%) or from government studies (Government of Canada, 2020) of the overall Canadian population (10.1%). Another study (Regahr, et al., 2019) observed that correctional workers specifically suffered from high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Research on a group of Ontario-based correctional workers (Carleton, et al., 2020) also identified panic disorder and alcohol use disorder as potential conditions caused by the requirements of prison work. A more recent study (Ricciardelli, 2023a) noted that cuts in funding and reduction of rehabilitation programs across the prison system were also contributing to the occurrence of PPTE as the unsupported infrastructure led to more hazardous conditions.

The purposes of this new study were to determine what aspects of correctional work were considered the most important to staff members in terms of assessing and improving the conditions causing such widespread mental health concerns.

“It is important to acknowledge how each type of stressor may lead to different mental health concerns…physical violence and injury—operational stressors—were most strongly associated with PTSD, while low support and job satisfaction, and a lack of appreciation—organizational stressors—were more apt to lead to symptoms of depression and anxiety.”

Methodology

Between 2018 and 2020, the research team administered an anonymous, confidential survey–based in part on the Correctional Worker Mental Health and Well-being Study–to 1,999 correctional workers across Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Yukon Territory. Respondents held a wide range of roles within the correctional system, including:

- Correctional and probation officers

- Program officers

- Nurses, rehabilitative, and other healthcare staff

- Administrative staff

- Managers

- Teachers

Distribution and recruitment for the survey was assisted by labor unions and government representatives, and research ethics boards at two independent universities provided ethics approval to move forward with the study. Additionally, the researchers provided protocols in the event that any participant was experiencing an urgent mental health crisis.

The survey was designed to be completed at the respondent’s convenience–the link was received via email, could be completed on either work hours or free time, and allowed the respondent to stop, save their progress, and continue later. It was determined that participants’ average completion time for the survey was 25-40 minutes.

Although the individual survey questions provided meaningful data, the key information being collected came from an optional item at the end of the questionnaire. Participants were provided with an open text field, and prompted: “If you have any additional information you would like to provide or additional feedback, please feel free to do so below.” Approximately 9.6% of those who finished the survey (192 participants) provided this feedback, which was then organized, categorized, and coded using QSR NVivo software.

Findings and Interpretations

The researchers found that when given the freedom to offer unstructured responses, they often took the opportunity to describe the physical and psychological toll of the work, coming from both operational and organizational sources. Themes that emerged included:

- Stigma against acknowledgment of mental health concerns

- Lack of supportive relationships with management and other leadership

- Stress related to employment policies on time off

- Inadequate treatment for mental health issues

- Suggestions for improving the work environment

The lingering effects of PPTE were discussed in 18.75% of survey responses. One excerpted response from a Saskatchewan correctional officer observed that: “Corrections is hard on the body and mind, it can wreck your only support systems through lack of time, energy, and understanding.”

Approximately 10% of respondents discussed a workplace culture that discouraged any discussion of mental health issues across all levels of administration, including frontline work and management. One correctional officer from Newfoundland and Labrador stated: “There are numerous Correctional Officers with mental health issues in our workplace. Some/most are too proud to ask for help. This is fear of what your co-workers will say about you, including management.” Others expressed that they needed to see change throughout the Canadian mental health system in terms of mental health frameworks, and that the stigma surrounding discussion of these issues could be dispelled by leadership.

“If correctional work is no longer to be ‘a job that honestly takes your soul with it’...then it is necessary to rethink how correctional workers can live and work with their PPTE and related mental health concerns.”

However, a significant number of respondents – nearly 32% – identified management issues and dysfunctional relationships within their organizational hierarchy as another major cause of stress. Managers were alleged to be unsupportive, and behaving as though mental health concerns were a personal issue rather than an institutional problem to be solved. As one Manitoba probation officer bluntly pointed out: “Senior management at our corrections facility have been quoted as saying ‘It’s not our problem’ regarding staff suicide AND staff mental health.” Bullying behavior was also specifically mentioned by 5% of respondents, with 80% of them saying that the behavior was being directed towards them by supervisors.

Management was also mentioned as a hurdle when it came to concerns about time off policies – approximately 29% of respondents had specific criticisms about how these were implemented in their facilities. A teacher from Manitoba described a workplace in which management was often “investigating” the use of sick time to ensure it was not being abused. They added in their survey response: “Corrections is not supportive of Mental Health concerns. The Attendance management policy is very anti Mental Health. The whole policy causes added anxiety and stress to any mental health concerns.”

Treatment options were brought up in 16.67% of responses, although in several instances the respondents had concerns about the quality of treatment available and the financial burdens placed upon them to receive it. One correctional officer from Saskatchewan stated that “the PTSD treatment that I received for 8 months was not helpful and mostly outdated,” while another correctional officer from Manitoba felt that “the department needs access to psychologists who are trained to deal with PTSD and workplace trauma.” Other responses discussed the possibilities of better training for peer support and the overall need to evolve the workplace culture of correctional facilities.

Conclusion

The results of this new study appear to validate and support previous research on the subject of mental health for corrections workers. The findings were consistent across an array of regions and facilities, and that the feedback provided also aligned with prior research focused on one Canadian province as well as research that employed more structured and targeted questions. The research team feels that their work illustrates the ongoing need to provide greater organizational support to correctional workers, as well as shift the culture towards open acknowledgment of mental health and the stress factors of corrections work. By doing so, there will be opportunities to lower the prevalence of mental health disorders within correctional staff.

“There is a need to support all correctional workers in recognizing their mental health needs, which is essential to create a space where all correctional workers are open to treatment, intervention, and support.”