First published in BMC Psychiatry in February of this year, a study by Anne Bukten, Suvi Virtanen, Morten Hesse, Zheng Chang, Timo Lehmann Kvamme, Birgitte Thylstrup, Torill Tverborgvik, Ingeborg Skjærvø & Marianne R. Stavseth examines the decade of 2010-19 among the prison populations in three Scandinavian nations (Norway, Sweden, and Denmark) to examine the pervasiveness of various mental health disorders – including substance use disorders (SUD) – within those incarcerated. The research observed a rising rate of such disorders even within an overall decrease in the number of prisoners, raising questions about what programs or systems may need to be implemented to answer this issue.

Background and Research Purposes

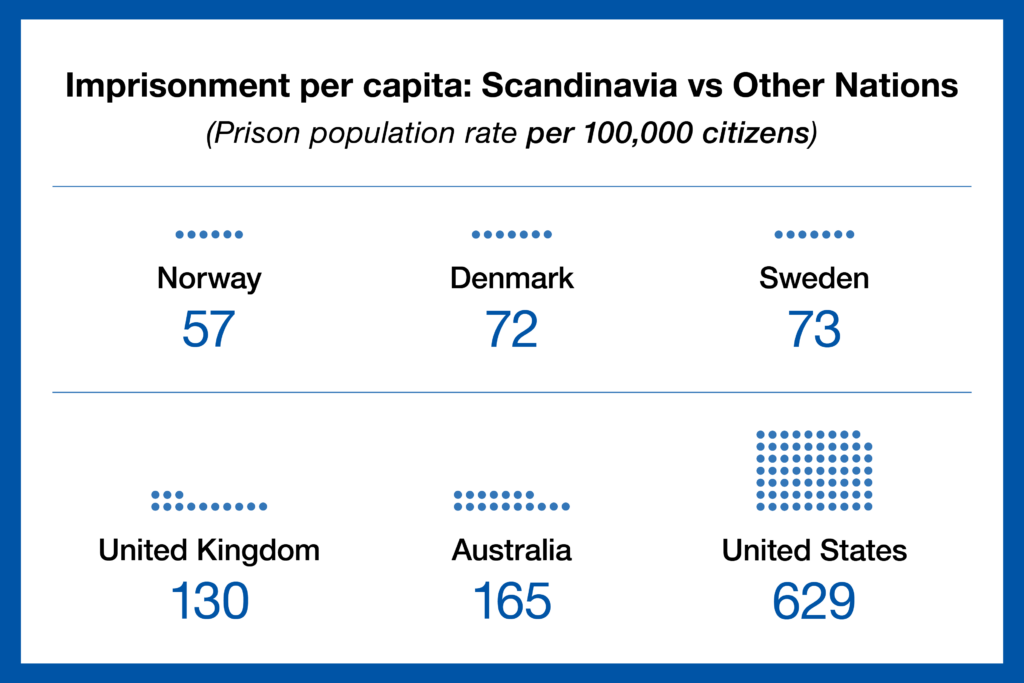

Recent studies have indicated that the global prison population has grown to over 11 million people, and that within this population there are significant rates of mental health disorders, often comorbid with substance use disorders. Several other studies of this circumstance have shown that these disorders can correlate to tragic outcomes after incarcerated individuals are released, including instances of suicide, substance overdose, or reoffending. Correctional systems within Scandinavian countries tend to have offenders with mental health disorders transferred to forensic care rather than prison. The lower rate of imprisonment, however, has not meant that there are lower rates of mortality within prisons or after release, which speaks to the likelihood that there remain high rates of mental health disorders among those incarcerated even within Scandinavian countries.

The researchers noted that prior prevalence-focused studies involved examination of only one disorder, while studies that considered comorbidity tended to focus on very specific combinations of conditions – such as depression and SUD – rather than a more general review. They also noted that prior studies of mental health disorders within the prisoner population used subject interviews, including retrospective study formats or self-reporting. The limitations of these methods included the potential for recall bias, colored by the psychological stresses of incarceration, as well as the difficulties of having non-medical professionals provide their own diagnoses. For these reasons, the researchers opted to use data from administrative registers, which contain detailed information on each prisoner including the duration of their incarceration. Through this data, the researchers identified three key goals:

- Estimate the prevalence of mental health disorders in the prisoner populations.

- Estimate the annual proportion of comorbid mental health disorders with SUD at the start of incarceration.

- Investigate changes in the prevalence of these disorders over time between 2010–2019.

“Comorbidity of mental health and SUDs is associated with a poorer treatment response, poorer adherence to medication, and a substantially higher risk of reoffending, when compared to those without comorbidities. Comorbidity poses great challenges to treatment planning, and thus it is critical that the criminal justice system has an accurate picture of the clinical health complexities of people imprisoned.”

Methodology

The study cohort across the three countries involved 119,507 prisoners who were over the age of 19 during the study period of 2010–2019, including those who had been incarcerated in high-security units and low-security units and those who were in pre-trial remand. Individuals serving their sentences outside of correctional facilities (eg, home detention) were excluded. Research was limited by the available register data during the study period, resulting in a cohort as follows:

- Norway – 50,861 prisoners, 2010–2019

- Denmark – 45,532 prisoners, 2010–2018

- Sweden – 23,114 prisoners, 2010–2013

The median age of the entire cohort during their first sentence ranged between 32-36, and women represented a profound minority of those imprisoned – approximately 7% within Denmark and Sweden, and nearly 11% in Norway. Within the cohort, the majority had only been incarcerated once during the study period, ranging from 63.9% in Denmark to 71% in Norway and 78.7% in Sweden.

Mental health disorders being assessed by the study were categorized using the document International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, which distinguishes them as follows:

- Organic mental disorder

- Substance use disorder (SUD)

- Schizophrenia and psychotic disorder

- Affective disorder

- Neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorder

- Disorders associated with physiological disturbances

- Disorders of adult personality and behaviour

- Intellectual disability

- Disorders of psychological development

- Childhood onset emotional and behavioural disorder

Addiction to tobacco has been excluded from this study, as have the following types of disorders:

- Specific developmental disorders of speech and language, scholastic skills, motor function

- Mixed specific, or unspecified disorders of psychological development

- Conduct disorders

- Emotional disorders, disorders of social functioning or other behavioural/emotional disorders with onset specific to childhood and adolescence

- Tic disorders

To assess the link between mental health disorders and incarceration, the national prison registers in these three countries were viewed alongside the national patient registers, which collect hospital data for those receiving specialist health care (excluding primary care, private clinics, or treatment from NGOs and social services), and sorted by unique PIN numbers.

Findings and Interpretations

The study made several key observations, including:

- In all three countries, the proportion of prisoners diagnosed with a mental health disorder was at least 50% – ranging from 50.8% in Sweden to 51.2% in Denmark, and 59.6% in Sweden.

- The most prevalent diagnoses were for SUD, depressive disorder, stress-related disorder, and ADHD.

- Comorbid SUD and other mental health disorders ranged from 21.7% in Sweden to 23.1% in Denmark and 29% in Norway, and were increasing over time.

- Disorders such as psychosis or schizophrenia presented at much higher rates within the study cohort than have been observed in the general population of these countries.

- Women were generally more likely to be diagnosed with a mental disorder and a comorbid SUD than men, despite comprising a significantly smaller proportion of the cohort.

- In all three countries, while the prison population went down over time, the prevalence of mental health disorders within that population increased.

Through a prospective study design, the researchers learned that one in three prisoners, through specialist healthcare, had been diagnosed with a mental health disorder prior to entering incarceration. Furthermore, the researchers hypothesize that the actual prevalence may be higher, since national patient register data requires individuals to first seek specialist health services.

Within the three Scandinavian nations, current policy remands offenders to forensic psychiatric care only when it is determined that mental illness or other conditions have rendered the accused unable to comprehend their actions at the time of the offense. The growing prevalence of mental health disorders within the study cohort indicates that these policies may need to be revisited and reconsidered, as those suffering from these disorders and SUD require psychiatric care rather than incarceration.

“Since individuals with concurrent disorders are more likely to access mental health services compared to those with substance use disorders or mental health disorders alone, our estimates likely represent a subset of individuals suffering from relatively severe psychopathology.”

Conclusions

The results of this study underline the need to offer effective mental health treatment options within the incarcerated population in both short-term and long-term settings. Since many offenders entering incarceration may already have been diagnosed with mental health disorders, SUD, or different comorbid conditions, it is crucial that any who have been receiving treatment prior to the start of their sentence have access to these same treatments during their period of imprisonment. This will require correctional institutions to examine their resources and upgrade their services to account for the rising population of prisoners in need of care. They must also work hand-in-hand with community agencies to ensure that after an individual is released from incarceration they have a path to recovery and reintegration within society, which will reduce negative outcomes such as recidivism or relapse.

Source: The prevalence and comorbidity of mental health and substance use disorders in Scandinavian prisons 2010–2019: a multi-national register study (Anne Bukten, Suvi Virtanen, Morten Hesse, Zheng Chang, Timo Lehmann Kvamme, Birgitte Thylstrup, Torill Tverborgvik, Ingeborg Skjærvø & Marianne R. Stavseth) https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-024-05540-6