A pilot study of the utility and effectiveness of video games designed for correctional intervention appears in the November 2024 issue of Criminal Justice and Behavior. The study is co-authored by Keegan J. Diehl, Robert D. Morgan, Christopher M. King, Paul B. Ingram, and Cooper Mitchell, and focuses specifically on Project Choices, a "serious" video game designed for justice-involved individuals that aims to reduce recidivism. Through a cross-over design study and follow-up surveys, the researchers sought to determine if Project Choices could provide as much engagement and immersion to the players as a game designed strictly for leisure purposes. The researchers also looked at the effects of gameplay on criminogenic thinking, self-perceived criminogenic risk, and social problem-solving.

Background

Project Choices was developed by Dr. Christopher M. King and Dr. Robert Morgan of the University of Southern Illinois – two of the authors of this study – in collaboration with Skyless Games. The game consists of 42 decision-making scenarios based on real-life events taking place during community reentry, and provides cognitive behavioral skills feedback for the decisions made by the player. Examples of scenarios include:

- Encountering individuals with criminal backgrounds

- Feeling overwhelmed by day-to-day responsibilities

- Facing the choice to resume an unhealthy, violent personal relationship

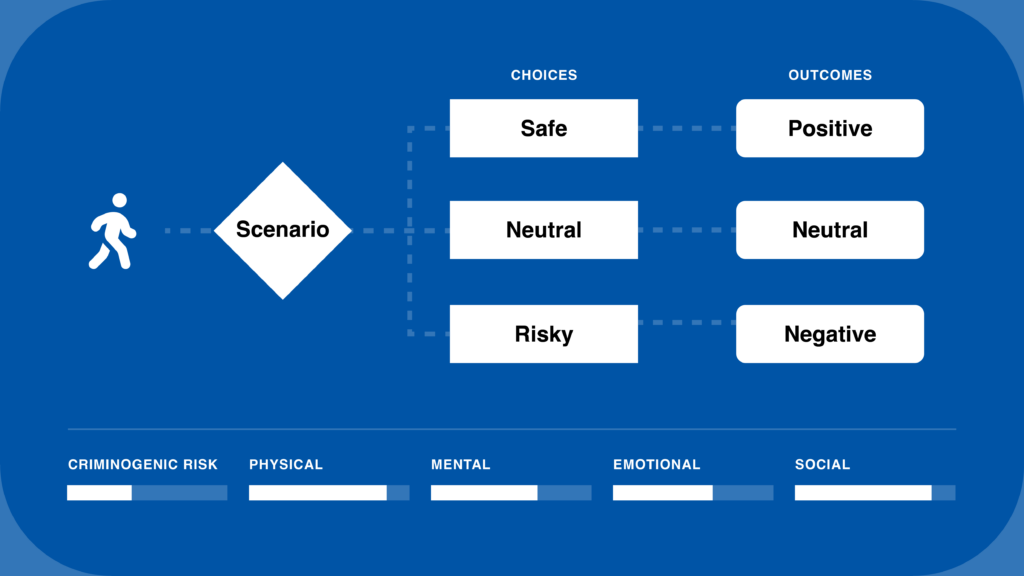

Over the course of two simulated game “weeks” the player is provided with choices in response to each scenario that are considered “safe,” “neutral,” or “risky.” The outcomes associated with each choice produce positive, neutral, or negative outcomes, which then alter the player’s in-game “functional statistics”:

- Criminogenic risk

- Physical status

- Mental status

- Emotional status

- Financial status

- Social status

Players receive feedback about the outcome probability associated with each option and are encouraged to make safer choices that lower their criminogenic risk and increase their other statistics. If too many of their choices lead to negative outcomes and the criminogenic risk statistic hits a higher threshold, the player’s game ends with the player’s character automatically reoffending.

This game is categorized as a “serious” video game, which indicates that it was developed for clinical purposes. Its potential use aligns with recent initiatives to address challenges in rehabilitation services using technology solutions, often referred to as “eHealth” options. These technology-assisted services allow for standardization, flexibility, portability, and reduced demands on providers within the corrections space. Several studies have shown that incorporating technology into corrections practices and interventions can reinforce positive decision making, and that justice-involved individuals respond favorably to their inclusion in their programs. This study focused on metrics of immersiveness and engagement for Project Choices, and the researchers further hypothesized that gameplay might lead to lowered risk of criminogenic thoughts and behavior.

METHODOLOGY

Participants

A pool of 43 participants was chosen from a mid-sized residential correctional institution (population approximately 150) in the southwestern region of the United States between June 2021 to January 2022. Any potential participants who were two months or less away from release were excluded. All chosen participants shared the following characteristics:

- Adult male

- Considered moderate to high risk

- Diagnosed with a substance use disorder

- Currently on probation

- Had community supervision revoked for noncompliance

- Enrolled in a cognitive behavioral program focused on substance use and criminogenic thinking, with an average participation of nine months

The average age of the 43 participants was 30 years old, with 59% identifying as White, 23% identifying as Black, and 42% reporting Hispanic ethnicity. They had served an average of five years and eight months under probation and had undergone treatment for an average of nine weeks.

Research Structure

The study took place over a course of six weeks, and split the participants into two groups. Each group received a baseline assessment using the following battery of surveys:

- Capacity Assessment Record for Research Informed Consent (CAR)

- Modified Game Engagement Questionnaire (mGEQ)

- Temple Presence Inventory (TPI)

- Psychological Inventory of Criminal Thinking Styles-Short Form (PICTS-SF)

- Perceived Risk Inventory (PRI)

- Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised: Short Form (SPSI-R:S)

All surveys except for the CAR were self-report assessments, designed to collect information about the participants’ levels of immersion in technology, engagement during gameplay, criminogenic thinking, self-perceived risk of offending, social problem-solving skills, and other relevant metrics.

After this assessment, the study employed a crossover approach in which one group would spend three weeks playing Project Choices in 30-minute sessions, three times per week, while the other group would play the puzzle-based video game Tetris (chosen as a control due to its neutral content) under the same conditions. After this period concluded, all participants received the assessments again before receiving a break of 12 days, which was followed by the groups switching games for another three weeks. The participants then received the assessments one final time at the study’s conclusion.

KEY FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATIONS

Over the course of the study, the pool of participants experienced significant attrition, with individuals withdrawing either due to disinterest or logistical difficulties.

- Within the Project Choices-first group, 8 of the 22 participants withdrew during the first three-week period, and 4 more withdrew during the second three-week period. Two-thirds of these withdrawals (8) were due to disinterest

- Within the Tetris-first group, 3 of the 21 participants withdrew during the first three-week period, and 4 more withdrew during the second three-week period. Five of the seven withdrawals were due to disinterest

"The study seemed to support the hypothesis that Project Choices offered engagement and immersion that was comparable to a leisure video game, and that this may offer potential for the use of clinical video games in correctional interventions."

Results for the 24 participants who completed the study showed that in terms of engagement, immersion, criminogenic thinking, and self-perceived criminogenic risk, there were not any statistically significant differences between the group that played Project Choices first and the group that played Tetris first. The researchers did observe a slight difference in social problem-solving skills for those participants who played Project Choices first that did not occur in the group that played Tetris first. The study seemed to support the hypothesis that Project Choices offered engagement and immersion that was comparable to a leisure video game, and that this may offer potential for the use of clinical video games in correctional interventions.

The researchers note that the lack of clear and consistent evidence of effects between the two groups could be due to a number of reasons, including:

- The study’s structure of two three-week periods per group might need to be expanded

- Project Choices gameplay might require supplemental feedback from a treatment provider

- Gameplay elements within Project Choices could increase the participant’s level of self-perceived risk

- Growing confidence in the game mechanics of Project Choices could decrease the participant’s level of self-perceived risk

The researchers did observe moderate to large effects for reductions in current and reactive criminal thinking—outcomes very relevant to criminogenic risk-reduction interventions—but further research is required to verify that these results are accurate.

CONCLUSIONS

As a pilot study, the researchers acknowledged that there were notable limitations, including the high rate of participant attrition, the likelihood that levels and methods of substance abuse treatment of each participant may have affected their responses, and the availability of other recreational video games within the facility. Logistical issues were also a factor, as the researchers often needed to communicate with facility staff to ensure that there was minimal interruption to gameplay sessions during day-to-day operations.

Regardless, even this limited data shows that further research into the use of “serious” video games like Project Choices for correctional rehabilitation may offer additional insights. The researchers suggest that stronger study designs with larger sample populations will be required, and that other studies may focus on other variables, such as the amount of time the games are played, the demographic makeup of the participants, and different criminogenic risk and needs outcomes. The game itself may also have utility in assessment of justice-involved individuals, which is worthy of separate investigation as well.

Note:

Co-author Cooper Mitchell was a recipient of the IACFP Student Research Award in 2024.