The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of social learning theory including its theoretical foundations, explanatory concepts, case examples, and how it applies to a correctional setting as a general theory of crime and deviant behavior.

Social Learning Theory: The Basics

Social Learning Theory (SLT) reinforces the idea that learning occurs within a social context. People learn from observing others’ behaviors and the outcomes of those behaviors (Astray-Caneda, Busbee, & Fanning, 2011). Albert Bandura, a major contributor to the field of social learning, explains that social learning is a continuous and reciprocal interaction between cognitive, behavioral, and environmental influences.

The basic tenant of social learning is that people learn from behaviors, and the imitated behavior itself leads to reinforcing consequences. Many behaviors that are learned from others produce satisfying or reinforcing results (Bandura, 1977). Social learning theory also helps to explain why people engage in, as well as refrain from, criminal behavior. It also explains how we conform to and violate norms, including the norms of one’s own group or culture. Furthermore, social learning theory focuses on social context and cognitive-behavioral variables, and not on individual characteristics (Akers, 1998).

Social learning theory is a general theory that encompasses social, non-social, and cultural factors that explain the acquisition and maintenance of and change in criminal and deviant behavior. Social learning theory also addresses factors that operate both to motivate and to control and/or prevent criminal behavior and to undermine conformity (Akers, 1998).

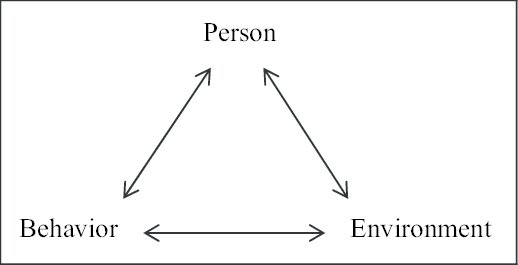

Social learning theory identifies three primary forces that explain human behavior. These forces are: 1) behavior, 2) environment, and 3) person (i.e. cognitive structure). These forces interact in a triadic, dynamic relationship, each subject to change, and can influence the others (Bandura, 1977). Bandura explains this triadic dynamic relationship as the changes in the external environmental trigger changes in our thoughts and emotions (i.e, our cognitive structure) that, in turn, produce changes in our behavior.

Social learning theory includes different types of reinforcement. These include:

- Positive reinforcement (strengthening of behavior through rewards);

- Negative reinforcement (strengthening of behavior through escape or avoidance of punishment;

- Positive punishment (painful consequences); and

- Negative punishment (removal of rewards).

All of these can be applied to both conforming and non-conforming (deviant) behaviors. Social learning theory emphasizes the balance of both positive and negative consequences.

Application

For a better understanding of social learning theory and how it applies to correctional settings, the following scenario is given to demonstrate the imitation of behavior through modeling.

John Doe is a 16-year-old male who was raised in a family environment that was conducive to spousal abuse since he was 10 years old. His father was an alcoholic and subjected his mother to physical, sexual, and mental abuse on a regular basis. As a result of his father’s abusive behavior towards his mother, he noticed that his mother would always treat his father with respect.

From now on, John learned to identify violence with power, respect, and dominance through creating fear in others. The end result is also viewing violence as the answer to social interaction.

As mentioned prior, behavior can also be positively reinforced, even if the behavior itself is deviant and criminal in nature (Akers and Jennings, 2009). The following is an example of positive reinforcement.

Philip is a 13-year-old boy who just recently started a new school after moving to a new community with his family. Since starting school, he has been teased constantly by several known bullies at school while walking through the hallways to class. Philip decides to punch one of the bullies in the face in front of his classmates. The other bullies then stop bullying Philip and take sides with him as well as other classmates who have been bullied.

In this example, Philip’s behavior of punching the bully results in an increase in social status among his classmates and a following of friends. His violent behavior towards the bully was, in turn, positively reinforced through this increase in social status and number of friends. Thus going forward, whenever he is encountered with a bully or someone who doesn’t like him, his answer will be to act violently towards them, because he has connected violence with greater social status and a peer following.

Observational Learning

Social learning theory focuses on the learning that occurs within a social context. It considers that people learn from one another, including such concepts as observational learning which has four components: attention, retention, motor reproduction, and motivation (Bandura, 1977).

- Attention: Individuals cannot learn solely by observation unless they perceive and attend significant features of the modeled behavior (Allen & Santrock, 1993, pg. 139).

- Retention: In order to reproduce the modeled behavior, the individuals must encode the information into long-term memory (Allen & Santrock, 1993, pg. 139).

- Motor reproduction: Once the behavior is processed from attention and retention the observer must possess the physical capabilities of the modeled behavior in order to reproduce such behavior (Allen & Santrock, 1993, pg. 139).

- Motivation: The observer expects to receive positive enforcement for the modeled behavior thus perpetuating the cycle to keep engaging in such behavior (Allen & Santrock, 1993, pg. 139.

People are both products and producers of their environment. According to Bandura, we learn by observing and interacting with our environment. Thus, we model our behavior after what is going on around us. For most of us, our internal attitudes and beliefs about the world come from the people who either parent us or with whom we spend significant time (Bandura, 1977).

As the old saying goes, “birds of a feather flock together.” In the context of the correctional setting, inmates will influence one another’s behavior in both conforming and non-conforming directions (Akers, 1991). Inmates will learn these conforming or non-conforming (deviant) behaviors from one another. The similarities in the particular inmates’ behaviors has an impact on their selection of friends and also the costs attached to continuing those relationships. If an inmate joins a group that is engaged in deviant behavior, this type of behavior only escalates after joining such group. Vice-versa, if the group models conforming behavior, then this type of behavior pattern is also increased.

Similar to social learning theory, Shaw and McKay’s social disorganization theory asserts that a culture that lacks social organization is a major cause of criminality (Bartollas, 1990). Accordingly, inmates are in a correctional setting, often because some type of deviant behavior was modeled from their prior environment (Sutherland, 1995). The correctional environment itself provides a platform to model both deviant behavior as well as positive behavior, thereby influencing the behaviors of inmates accordingly.

Consequences can be a matter of perception. People will typically avoid behavior which results in negative consequences, but will engage in behaviors they perceive will have a positive outcome. An inmate may find what others would experience as a punishment to actually be rewarding. Inmates may not see prison, jail, or another correctional setting as a negative consequence. Furthermore, they may not see being placed in segregation or “the hole” as true “punishment” for their behavior.

A good example of negative behavior followed by negative reinforcement are those inmates who engage in deviant behaviors for secondary gain. A person will not punish himself, unless this punishment is paired with a reinforcement. Think of it as the child who acts out and then is rewarded with candy, so he/she will stop crying. That child then learns to cry to get candy.

Parallel to the correctional setting, inmates may act out through self-injurious behavior with no suicidal intent, but do so because they know they will get extra attention from mental health and medical. If the self-injury is bad enough, they will be sent to an external hospital, where they will get to see the outside world, be fed different food, and receive other non-correctional experiences. The inmates who have a repeated pattern of this behavior are well-known to staff, and the offender knows this. It becomes a bargaining chip to deter them from engaging in other negative behaviors. They may request such things as extra trays, books, or paper and pencils to write letters; things that are not typically allowed, if they are on a mental health or behavioral watch in exchange for the promise of good behavior. They begin to correlate their negative behavior with rewarding consequences, such as extra food, more time in recreation, and more staff attention as a reward for acting out.

Thinking Pattern

As is the case with most inmates, there is almost always an underlying thinking pattern that affects attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. Having an antisocial style of thinking creates entitlement, selfishness, and escape from the expected norms. Inmates view themselves as unfairly treated and have learned a pattern of defiance throughout their lifespan. This results in a hostile attitude that becomes part of a learned cognitive thinking pattern that is self-destructive. The offender takes the victim stance that creates a sense of outrage, power, and self-gratification (Ferns, 2006). Relationships with others are characterized by a power struggle, and cooperation is for mere convenience. Winning to some inmates is forcing someone else to lose, whether they be staff or another offender. Winning in this fashion is how they have been taught to win, and the only real sense of gratification and satisfaction they are accustomed to. Whether they “win” or “lose,” it reinforces their negative cognitive style of thinking and creates a cycle of self-destruction (Ferns, 2006).

What Succeeds?

Effective interventions are those that target criminal beliefs and replace them with more effective strategies for change. This includes instilling new attitudes, beliefs, and modalities for change by providing the opportunity to change through programming or directed interventions.

As mental health practitioners interact with inmates, this is an opportunity to disrupt the deviant type of thinking that leads to criminality. This type of thinking is often automatic and has been reinforced by their environment prior to and during incarceration. Correctional facilities’ top priorities are security and safety through control. While the focus is mainly on control, we must also support and facilitate change in inmates and target how inmates think to mitigate their internal motivation for deviant behaviors.

In A General Theory of Crime (1990), Michael Gottfredson and Travis Hirschi argue that low self-control is a cause for criminality. Those with low self-control have a preference for excitement and impulsive behaviors. They also possess minimal frustration tolerance and focus on immediate gratification without regard to the long-term consequences of their actions (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990, 89). Increasing inmates’ sense of control in a controlled environment can be challenging, but seeking out opportunities for perceived increased control by inmates could be advantageous in this regard.

Conclusion

The goal is to provide treatment to inmates that will allow them to function more independently, responsibly, and with increased self-control. This will increase their safety and security while incarcerated, as well as provide them with the skills and abilities to prepare them for successful re-entry into the community.

It would be helpful if all correctional staff that frequently interact with inmates, including but beyond mental health providers, prioritize learning how to interact with inmates based upon social learning principles in order to effectively recognize and target the negative thinking patterns behind criminal behaviors in their daily work interactions (Ferns, 2006). Continuing to implement change and modeling positive behaviors is paramount to reduce deviant behaviors in the correctional population both during incarceration periods and after release.

* References available upon request

About the Authors

Tyler Ryan, Ph.D. is a correctional psychologist who has worked in a variety of correctional environments in Kentucky (USA) through Shelton Forensic Solutions, LLC. His interest is in applying family systems theory to incarcerated populations to improve relational dynamics between correctional professionals and inmates and to reduce maladaptive inmate coping strategies.

Sarah Shelton, PsyD, MPH, MSCP is the Founder and CEO of a large multidisciplinary forensic company with locations across seven states. Her company takes the concept of integrated care in medical systems and applies that approach to correctional and legal systems. She has a Doctorate in Clinical Psychology (PsyD) (Spalding University – APA Accredited), Graduate Specialization in Applied Forensics (Chicago School of Professional Psychology), a Master of Public Health (MPH) degree (Medical College of Georgia), and a Postdoctoral Master of Science in Psychopharmacology (Fairleigh Dickinson University).

Dr. Shelton has served as faculty in graduate Psychology, Public Health, and Criminal Justice programs at multiple universities since 2006. She also has made significant contributions as a volunteer and served in the leadership positions of multiple professional organizations. She currently is president of the IACFP Board. She was also most recently the Chair of the Board of Directors and President of the National Register of Health Service Psychologists (NR) in Washington, D.C.