The last issue of the IACFP Bulletin included a summary of recent research examining the relationship between solitary confinement and mental illness of adults in corrections. Readers were invited to answer four questions about their experiences, from the perspective of practitioners. Those questions were:

- Have you changed your policy on placing incarcerated persons in isolation cells over the last five years?

- Are you aware of criminal justice systems that have either not allowed mentally ill persons to be placed in isolation cells or that place an upper limit on their time in this type of confinement?

- As a practitioner, how do you assess an incarcerated person’s functional impairment? How do you communicate that to security staff?

- What interventions do you utilize to reduce behaviors associated with mental illness as an alternative to past utilization of isolation cells?

The responses we received highlighted three jurisdictions that have policies and practices practitioners should know more about if they want to make improvements in the treatment of the mentally ill in secure settings. We will highlight one in each of the next three issues of the IACFP Bulletin. This issue will focus on the Oregon Department of Corrections (Oregon DOC) in the United States. This article is based on an interview with Gabe Gitnes, one of two Assistant Administrators of Behavioral Health Services, Oregon DOC; supporting documentation provided by Ms. Gitnes; and information available on the internet.

Oregon DOC History

Ten years ago, Oregon DOC was in a similar position as many corrections organizations now find themselves. They had a high percentage of adults in custody considered to be Seriously Mentally Ill (SMI) who were exhibiting violent behaviors. These behaviors resulted in individuals with SMI being placed in the Intensive Management Unit and long-term solitary confinement. The organization committed to change that.

The Behavioral Health Unit was, at that time, considered to be a diversion from the Intensive Management Unit for those individuals with serious mental health issues. Their journey from that time to now relies on partnerships, experts, culture change, a commitment to constantly updating and expanding clinical practice and a focus on both the adults in custody and the staff who work with them as humans, rather than solely on restrictive housing as a correctional practice.

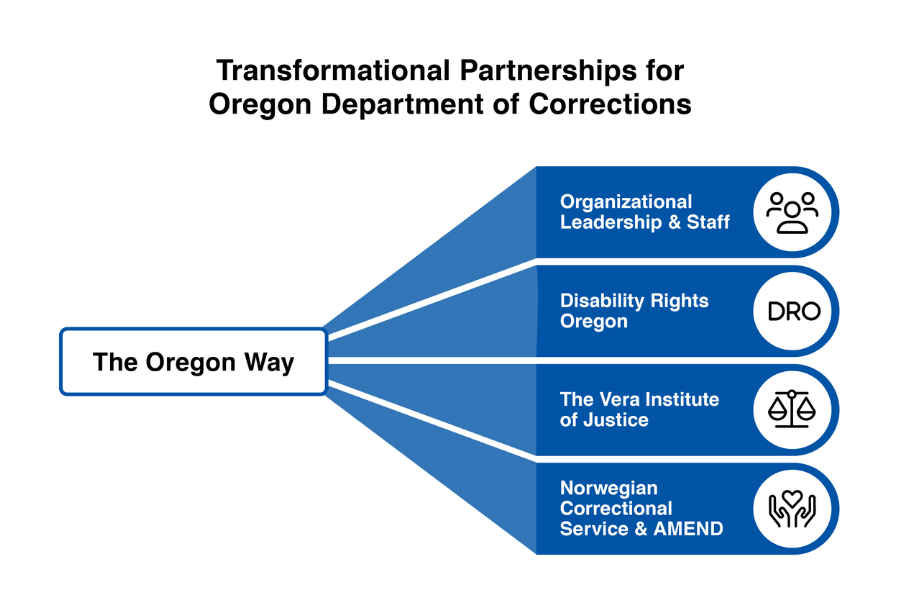

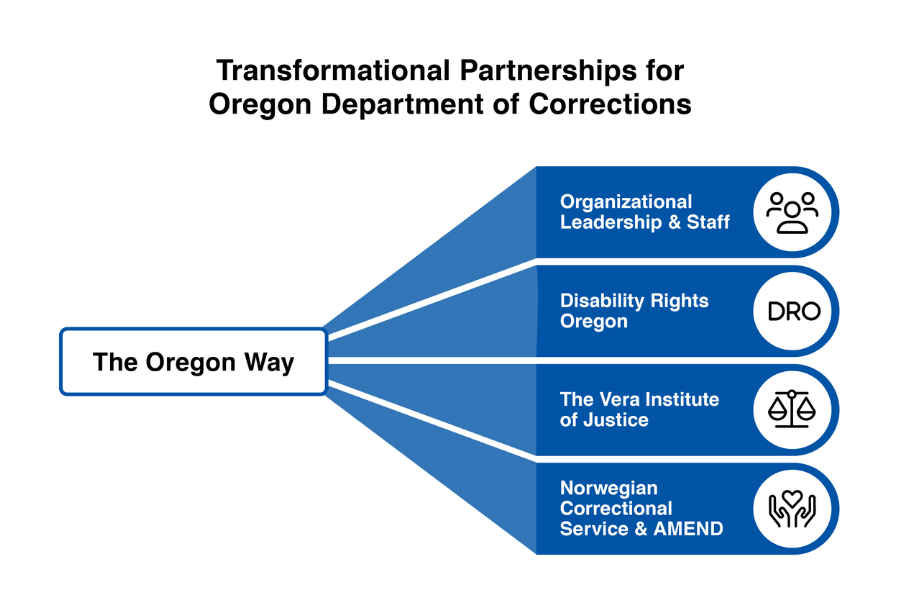

Significant Partnerships

There are four significant partnerships that have informed the transformation that has taken place in Oregon DOC.

Perhaps the most significant partnership to identify is the one between organizational leadership and staff. ODOC Leadership and staff accoss divisions recognized the need to develop effective treatment programming while maintaining safety for adults in custody who struggle with serious mental illness and who also struggle with behavioral disturbances. This included a significant expansion of the types of treatment offered, increased collaboration, training and support for the professional staff working within the treatment program (both behavioral health, security, and others), and the establishment of a mental health clinic outside of the adults in custody’s living environment. The leadership and collaboration evident among all these individuals have been critical to the transformation that has taken place in Oregon over the last ten years.

A second critical partnership has been with Disability Rights Oregon (DRO). In 2015 they wrote a report entitled “Behind the Eleventh Door” that led to a signed agreement between DRO and Oregon DOC to transform the treatment of prisoners with mental illness and to bring the organization into compliance with constitutional standards of care. Over the next six years DRO documented their oversight and partnership with DOC in annual reports.

A third partnership that informed the movement of Oregon DOC away from the use of solitary confinement was with the Vera Institute of Justice (Vera). Vera worked with five jurisdictions over a period of time to consider alternatives to such confinement and to provide technical assistance to each one. The results of that initiative are summarized in “Rethinking Restrictive Housing” (May 2018). While this work was not specific to the treatment of adults in custody with mental illness, it was an important partnership for Oregon DOC during the transformation process.

A fourth partnership that has been instrumental in the culture change within the Oregon DOC is with the Norwegian Correctional Service and the University of California San Francisco’s AMEND program, which resulted in the development of “The Oregon Way.” The AMEND program is focused on two issues: segregation reform and staff well-being. The link for “The Oregon Way” connects to an article describing the culture change that has been instrumental in the transformation at Oregon DOC. This video highlights those changes at the Oregon State Penitentiary in the Behavioral Health Unit, which provides evidence of how transformation can occur with adults in custody who present significant challenges to traditional correctional systems. The focus is on humanizing and normalizing the experience for both adults in custody and for the staff who work with them.

Critical Policy Changes

Today, the Oregon DOC has a continuum of care and services available to adults in custody who are mentally ill. The continuum is as follows:

- General Outpatient

- Services

- Mental Health Unit (still outpatient)

- Day Treatment Units

- Intermediate Care Housing

- Behavioral Health Unit

- Mental Health Infirmary

Adults in custody are placed in a level of care based on their individual needs. Two important policy changes support the levels of care:

- First, rather than following the practice of an SMI designation being fairly prescriptive and including only specific diagnoses, Oregon DOC now defines SMI as any diagnosis with significant functional impairment. While there are three exceptions, this definition changes the focus to functional impairment and to increasing the level of functioning through treatment.

- Second, the assessment and the treatment plan are individualized and based on what will meet the needs of the adult in custody with significant functional impairment.

A key policy change has been to view out of cell time as a necessity and not as a privilege. It is also viewed as necessary for individuals to become lower risk to engage in violent and self-harming behavior. For clients who are high risk or reluctant to come out of their cell, a resource team focuses on identifying activities that the adult in custody enjoys. They view these activities as motivators to engage them and to take better care of themselves. That same approach is used to reduce uses of force in the agency’s in-patient mental health units. The policy and practice shift has been to get their needs met versus forcing them to do something (e.g., come out of cell).

Recreation and leisure activities are part of treatment. Outdoor and indoor recreation has been expanded. Safe day rooms have also been built, including specialized program desks, to allow more congregate activity without adults in custody hurting one another.

A more recent policy change is that while many of these individuals are classified as “maximum security,” they can now engage in movement without restraints. The movement includes leaving a housing unit and walking to the mental health clinic. The decision on use of restraints is now based on imminent risk, rather than on custody level. This policy change has significantly changed the relationship between security personnel and adults in custody and reinforces healthier interactions.

The most recent policy changes are:

- No one in the behavioral health unit (BHU) can be sanctioned to the disciplinary segregation unit. In the past, if an adult in custody came to the BHU as a diversion from administrative segregation, they could receive a disciplinary sanction to disciplinary segregation status.

- Behavioral Health Services Clinical Practice has updated its mental health codes and levels of service to identify a client’s Level of Functioning based on clinical presentation, assessment of functioning, and the mental health provider’s clinical judgment. This establishes and identifies a level of mental health care for clients consistent with the community.

Menu of Interventions

Overall, the menu of interventions is based on behavior therapy and social learning theory. The primary treatment approach is Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT). They offer twenty-five different types of group therapy. And, every individual has an individual treatment plan with an average goal of at least 10 hours of structured therapeutic activity and 10 hours of unstructured recreational activity each week.

Most of the individuals who are in the BHU have demonstrated violent and assaultive behavior. They represent the top 2% of dangerous behavior within the prisons. And, the goal of treatment is to reduce this behavior by engaging them in healthy, normal, and focused treatment activity. They are able to transition to lower levels of intervention in the continuum of care to allocate mental health resources based on their clinical needs.

In addition to individual and group therapy, as well as other therapeutic activities, the menu of interventions and support may be: weighted blankets, music, art, sports activities or equipment, games, earphones, etc. based on individual needs and activities that the adult in custody may enjoy.

Summary

The Oregon DOC has engaged in an intentional effort to change its culture and to normalize the correctional environment for adults in custody and for DOC staff. They have also made significant efforts to not just say that they do not want the mentally ill to be placed in segregation or restricted housing but are taking steps to ensure their goal is a reality. Though they acknowledge that there is more to do, their journey to transform their system, treatment, and staffing is a worthwhile model for others.

* References available upon request.

Cherie Townsend is the IACFP Executive Director. She also works as an executive coach and consultant. Ms. Townsend previously worked as a leader and practitioner in juvenile justice systems for nearly 40 years.