Trauma-informed care is one framework that can support youth who have been involved in the court system (Epstein & Gonzales, 2017; Kerig, 2012; Saar et al., 2015). This care framework requires a basic realization and understanding of how traumatic experiences might impact individuals and communities (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). Trauma-informed care aims to recognize this trauma, promote healing, and avoid re-traumatization. Here, we provide an overview of existing practices, current projects, and areas for further research.

Trauma-Informed Care

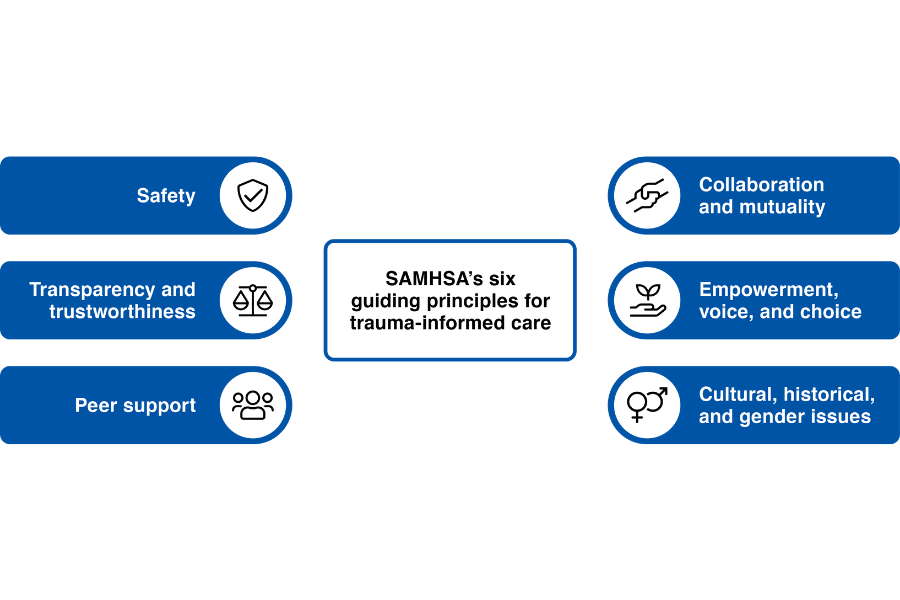

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] (2014) has played a crucial role in the development of these practices. In 2014, SAMHSA put forth six guiding principles for trauma-informed care:

- Safety;

- Transparency and trustworthiness;

- Peer support;

- Collaboration and mutuality;

- Empowerment, voice, and choice; and

- Cultural, historical, and gender issues.

Traumatic events may leave individuals feeling unsafe and powerless. When youth who have been exposed to trauma are not met with trauma-informed care, they may seek out alternative methods of coping with their distress. For example, they may physically remove themselves from their surroundings by running away or use substances to alter their emotional and cognitive states. Still, others may misbehave at school or engage in violent behavior in an effort to maintain some power and control over their surroundings. Alternatively, when youth are met with validation, counseling, and resources to regain those feelings of power and safety, they may feel empowered to work toward a life of healing and recovery that is crime-free.

The Cycle of Violence

Those involved in the juvenile legal system are often referred to as “offenders,” “criminals,” or “delinquent youth.” The people affected by their crimes are considered the “victims.” This false dichotomy fails to recognize that youth involved in the system are often both—a victim and an offender. Estimates suggest between 70-90% of youth involved in the juvenile or criminal legal systems have been exposed to violence or experienced some type of trauma (Abram et al., 2004; Dierkhising et al., 2013; Ford et al., 2008). These traumas include physical and sexual abuse, witnessing domestic violence at home, and witnessing violence in the community, among others.

Exposure to violence and trauma during childhood is related to a number of negative outcomes including mental health concerns, poor academic achievement, and difficulty with employment and relationships (Corman & Mocan, 2005; Dierkhising et al., 2013; Schwartz & Gorman, 2003; van Gelder et al., 2015). Compared to youth who have not experienced trauma, youth who have been exposed to violence are more likely to engage in violent behavior and commit violent crimes such as armed robbery, property damage, and assault (Baskin & Sommers, 2014; Currie & Tekin, 2012; Fox et al., 2015).

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) is one framework that helped conceptualize the victim-offender overlap. Felitti and colleagues (1998) examined seven negative childhood experiences and their effect on health outcomes in adulthood. Studies have found that the more ACEs an individual has, the more likely they are to experience future victimization, substance use, mental health issues (e.g., anxiety and depression), and criminal justice system involvement compared to those who have experienced fewer or no ACEs (Buffington et al., 2010; Centers for Disease Control, 2013; Felitti et al., 1998). Researchers have since expanded this framework to include ten different adverse events, which include: physical or emotional neglect, physical or emotional abuse, witnessing domestic violence, household mental illness, and parental incarceration (Anda et al., 2010; Baglivio et al., 2014; Centers for Disease Control, 2013).

Specific to youth, researchers have found that youth who have a higher number of ACEs are more likely to experience anxiety, depression, engage in violent behavior, use substances, and come into the legal system due to truancy and status offenses (Copeland-Linder et al., 2010; Flannery et al., 2007; Lansford et al., 2002; Saar et al., 2015). In particular, Baglivio et al. (2014) found that an increased number of ACEs led youth to be more likely to be involved in the juvenile legal system. Given the prevalence of ACEs and trauma among justice-involved youth, it is imperative that the juvenile system responds to and helps to heal this trauma while youth are in the system. Doing so may not only prevent future delinquency and crime, but may also impact these youth in other ways that both stop the cycle of violence and allow them to lead healthier and more productive lives.

Trauma-Informed Care & Juvenile Detention

In 2015, 28 bills were introduced to the U.S. Congress with explicit calls to implement trauma-informed policies and practices (Purtle & Lewis, 2017). Many of these were related to addressing trauma in schools, the child welfare system, and the juvenile justice system. Further, leading institutions have expressed the importance of trauma-informed care for children and youth (e.g., Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Child Traumatic Stress Network, and the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency). The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) has paved the way for these practices to come to fruition with the creation of trauma-informed trainings and programs, educational materials, and research on the symptoms, experiences, and impacts of trauma in youth. Over the last two decades, trauma-informed screenings, assessments, trainings, and treatments have been developed for at-risk and delinquent youth (Black et al., 2012; Zettler, 2020). Overall, it appears that the juvenile justice system is taking the calls for a trauma-informed system seriously.

The juvenile justice system has been working to reduce the number of youth formally processed through the courts; however, detention centers remain a common response to juvenile delinquency. Youth detention facilities were developed as one response to delinquent youth, often as a short-term holding facility until youth are formally adjudicated or while awaiting placement. While it is important for all aspects of the juvenile justice system to acknowledge and address this trauma, detention centers may be one key area within the system to target for trauma-informed practices. A core component of trauma-informed care is reducing re-traumatization. Given the nature of detention centers as a secure placement and the practices within the facilities (e.g., strip searches, pat downs, potential for loud noises and bright lights), re-traumatization is likely to happen (Branson et al., 2017). As such, the remainder of the discussion here will focus on youth detention facilities.

Several regional and state-wide evaluations of trauma-informed practices have been conducted providing support for multiple programs. Some of these programs provide specific intervention plans for youth (e.g., Trauma Affect Regulation for Education and Therapy, Sanctuary, Trauma Systems Therapy, Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competency), while others are designed for staff education and training (e.g., Think Trauma, Child Welfare Trauma Training Toolkit, and the Bench Card for the Trauma-Informed Judge). For example:

- Marrow and colleagues (2012) compared the impact of Trauma Affect Regulation for Education and Therapy (TARGET) with treatment as usual and found the TARGET group used seclusion six times fewer than treatment as usual, a decline that continued for eight months after the intervention was first implemented.

- Olafson and associates (2018) conducted a pilot test of Trauma and Grief Component Therapy (TGCT) in six residential facilities in Ohio and used Think Trauma as the staff training. Depression, anger, posttraumatic stress symptoms, dissociation symptoms, and incident reports all declined from pre- to post-test (Olafson et al., 2018). Qualitative analyses identified specific practices staff changed during the intervention period, such as knocking on doors before entering youths’ rooms and working with youth on breathing and other coping strategies when they were stressed (Olafson et al., 2018). Staff also report benefits from trauma-informed care implementation.

- In Los Angeles, Dierkhising and Kerig (2018) incorporated trauma-informed practices into the Gang Reduction and Youth Development program in Los Angeles. Staff reported an increased knowledge of trauma, an increased ability to screen for and respond to trauma, greater awareness of their own triggers, and feeling better equipped to use self-care practices to prevent vicarious trauma (Dierkhising & Kerig, 2018).

Other trauma-informed care interventions in juvenile facilities include utilizing trauma-specific assessments for risk factors and needs, implementing trauma-informed care in case management and planning, and incorporating psychoeducation regarding the effects of trauma into programming for youth. Unfortunately, while there is agreement around the need for trauma-informed practices and an understanding of the overarching values, there is a lack of consensus around what “trauma-informed” actually means in practice (Bartlett et al., 2016; Branson et al., 2017; Zettler, 2020).

What We Do & Don’t Know → Current Projects

Although there has been widespread adoption of trauma-informed programs, there is a lack of consensus around what trauma-informed practices encompass and how to transform the guiding principles of trauma-informed care to concrete policies. In a systematic review of evaluations of trauma-informed practices, Branson and colleagues (2017) found 71 different recommendations for policy and practice. These practices fell into three major areas:

- Clinical services (e.g., screening and assessment, evidence-based interventions, and cultural competence);

- Agency context (e.g., increasing youth and family engagement, staff training and support, and agency practices and leadership); and

- System-level recommendations (e.g., cross-system collaboration, system level policy and procedures, and quality assessment and evaluation).

As a result of this review, Branson and colleagues (2017) recommend a study of a nationally representative sample of the frontline staff and administration to examine the core components of trauma-informed care. Given the widespread support for developing and implementing trauma-informed care within the juvenile justice system, it is important to understand what practices are being adopted.

Currently, our research team at the University of Cincinnati is collecting data regarding the use of trauma-informed care in youth detention facilities. This project surveys roughly 150 juvenile detention facilities across the United States, using information from staff members and administrators. Staff members and administrators complete the 30-minute survey. Survey questions were developed utilizing a number of sources including the SAMHSA principles, the NCTSN Trauma System Readiness Tool, the Think Trauma Evaluation Questionnaire, and others.

The survey will inquire about staff trainings, staff and youth awareness and education about trauma, evidence-programming, screening and assessment practices, vicarious trauma support for staff, reducing re-victimization of youth, adherence to principles of trauma-informed care, barriers to implementation, and consideration of gender, race/ethnicity, cultural, and other identity aspects. Survey data will provide a broad picture of how trauma-informed care has been implemented in youth detention facilities across the United States, as well as a basis for operationalizing principles and core concepts.

Further, comparisons can be made across region, size, and other facility characteristics. At the conclusion of the survey, respondents are invited to participate in follow-up interviews. Our team plans to complete roughly 30 interviews with detention staff and administrators to get a deeper understanding of the trauma-informed practices implemented at their facility.

Conclusion & Implications

In 2012, the Report of the Attorney General’s Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence cited trauma-informed care as one of the key initiatives for the juvenile justice system. Given the prevalence and extent of experiences of trauma among youth in the juvenile justice system and the understanding that traumatic experiences are important to consider in pathways to delinquency, system actors and scholars alike agree on the importance of taking on the challenge of implanting trauma-informed care into juvenile justice practices (Dierkhising & Branson, 2016; Kerig, 2013; Marrow et al., 2012; SAMHSA, 2014).

While great progress has been made in advocating for trauma-informed care, the identification of principles for these practices, and the development of trauma-informed programming (e.g., trauma-focused therapy), there is still much to be done in terms of outlining specific implementation of this overarching framework. The information gathered from the current study will allow for the development and implementation of trauma-informed practices, trainings, and evaluations. Understanding what practices are being utilized is an important first step in knowing what actually works for the community being served, identifying gaps and barriers, and operationalizing principles into practices.

* References available upon request.

About the Author

Nicole McKenna is a doctoral student in the School of Criminal Justice at the University of Cincinnati. She received her M.S. in Criminology and Criminal Justice from Arizona State University in 2019. Her research focuses on girls in the juvenile legal system, the victim-offender overlap, and trauma-informed responses within the legal system. Her current research projects examine gender differences in needs and services provided to youth in the system, as well as trauma-informed care in juvenile detention facilities. Nicole’s research has been published in Criminal Justice and Behavior, American Journal of Community Psychology, and Feminist Criminology. She recently secured grant funding to examine trauma-informed practices in juvenile detention facilities across the United States. Nicole was a 2020 IACFP Student Research Grant Award recipient.