It is crucial for agencies to provide gender-specific custody and supervision training to learn how to appropriately respond and motivate their positive behavior. Women are held accountable for their behaviors, but done so in a gender-responsive and trauma-informed manner. In this article, we discuss the need for gender-responsive care, successful approaches being utilized in justice settings, and considerations for future research and programs.

Why Gender-Responsive?

Women are the fastest growing group within the criminal justice system (Zeng, 2020). While men remain the majority of persons involved in the criminal justice system, the number of justice-involved women has grown nearly 500% since 1980, to more than one million in 2021 (The Sentencing Project, 2022). While there are fewer women involved in the justice system than men, women are perceived as being more challenging to supervise by justice officials (Dodge, 1999). Women are largely perceived as “manipulative” and “needy” and often are treated more harshly than justice-involved men (Alder, 1998; Baines & Alder, 2016; Belknap et al., 1997; Bond-Maupin et al., 2008; Kempf-Leonard & Sample, 2000; Olson et al., 2003).

Such perceptions of women’s behavior signal insufficient training and understanding of justice-involved women’s unique life experiences and pathways into the justice system. The fact that women are naturally more verbal, with a multitude of psychosocial needs, causes frustration for staff who are untrained to work with them specifically.

Women’s Pathways

Men and women share certain risks and needs for justice involvement. Both groups have risks and needs related to the Central Eight, identified by Bonta and Andrews (2017). These risk factors are:

- History of antisocial behavior,

- Antisocial personality traits,

- Criminal peers,

- Criminal thinking,

- Substance abuse or dependence,

- Family/marital strain,

- Educational attainment/employment, and

- Lack of prosocial leisure activities.

Some of these criminogenic needs are more relevant to men than women (e.g., antisocial attitudes, lack of prosocial leisure activities), while others are more prevalent among women (e.g., economic strain and substance abuse). While the development of these risk factors was evidence-based, research in this area has primarily been conducted with samples of men/boys, with few, if any, women/girls, yet generalized to all (Gobeil et al., 2016). This type of research strategy is known as the “add women and stir method” of criminology. Women’s unique experiences are lost in this type of research (Chesney-Lind, 2006).

Since the 1980s, researchers have investigated the unique routes women take to justice involvement. They have found that women and girls have distinct pathways to justice involvement compared to men and boys. At their core, women’s pathways center on issues such as childhood victimization, dysfunctional and traumatic relationships, and family strain (Auslander et al., 2018; Brennan & Jackson, 2022; DeHart et al., 2013; DeHart, 2018; Salisbury & Van Voorhis, 2009). Their pathways are largely relational and lead to behaviors such as substance abuse, economic crime, and struggles with mental health.

Justice-involved women often experience “triple jeopardy,” meaning they have unique challenges related to class, race, and gender to promote their involvement in the justice system (Bloom, 1996). These women largely come from backgrounds with high levels of economic instability, trauma, mental illness, and abuse of drugs and alcohol. Women are also more likely than men to be primary caretakers of children with little or no familial support and unreliable or abusive partners. Upon release, they often return to these environments without support to address these original strains. These differing pathways, if not addressed, contribute to future recidivism. Addressing women’s needs requires interventions built around their experiences (Bloom et al., 2003; Gobeil et al., 2016; Messina & Esparza, 2022; Salisbury & Van Voorhis, 2009; Van Voorhis et al., 2008, 2010).

Additionally, the types of crimes committed by men and women differ. Women are incarcerated more often for property and drug crimes and are less likely than men to be incarcerated for violent crimes (Carson, 2022). Women’s crimes are generally categorized as "survival based" such as theft, prostitution, self-medicating with drugs or alcohol, and retaliatory acts of violence. Victimization, whether physical or sexual, and trauma is at the heart of many women’s criminal activity (Barlow & Weare, 2019; DeHart, 2018; James & Glaze, 2006; Jones et al., 2018; Messina & Grella, 2006; Reichert et al., 2010; Steiner et al., 1997).

Research demonstrates that most justice-involved women experience mental illness (75%), substance abuse (85%), or a co-occurrence of the two (DeHart et al., 2014). Treating justice-involved women from a "gender-neutral" standpoint runs the risk of returning women to their communities and family with the very same issues that led to their involvement in the first place, as well as the added strain of being justice-involved.

Gender-Responsive Approaches

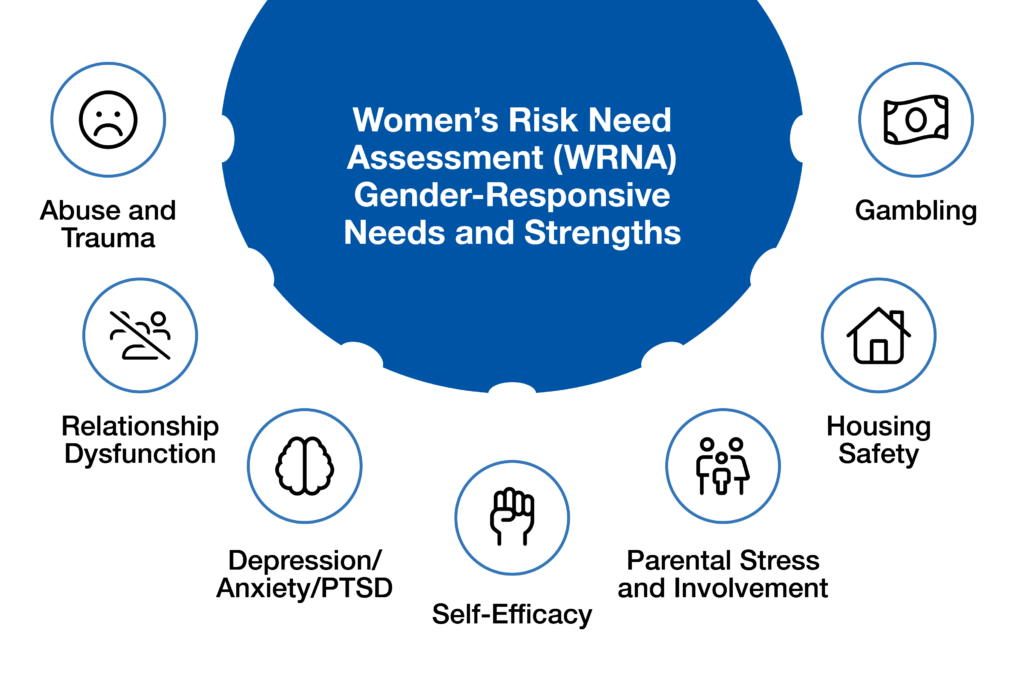

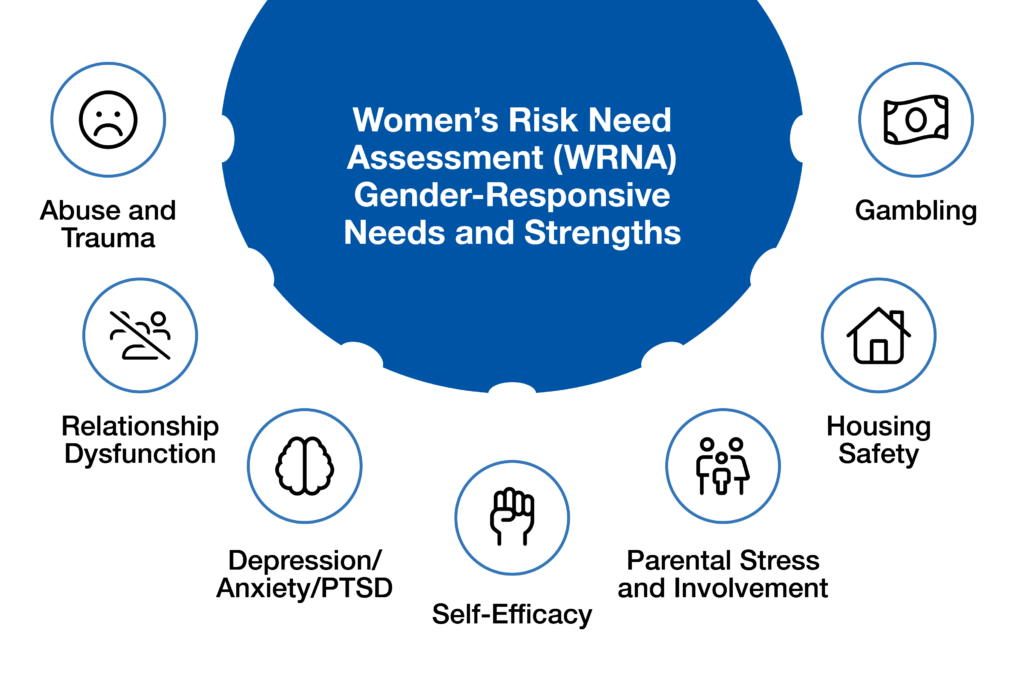

Over the last 30 years, researchers have focused on identifying not only women’s differing pathways to the justice system but also ways of assessing and treating their risk factors and needs. Several evidence-based tools exist to support agencies in applying gender-responsive strategies. The Women’s Risk Need Assessment (WRNA) was one of the first gender-responsive tools available for justice agencies (Van Voorhis et al., 2010). Originally funded by the U.S. National Institute of Corrections, the WRNA is an evidence-based, gender-responsive risk and need assessment that has been validated for women while in institutions, at pre-release, and on probation. In addition to gender-neutral risk factors, the WRNA addresses seven gender-responsive needs and strengths:

Tools like the WRNA allow justice staff to identify gender-specific risk factors and strengths, and focus case management practices on more fully addressing women’s needs. Notably, the WRNA is a recommended instrument by the United Nations (UN) Office on Drugs and Crime to adhere to the UN’s Bangkok Rules, which afford human rights protections to justice-involved women (UNODC, 2020).

Assessments and interventions for women that respond to the unique experiences of their gender are critical for reducing recidivism (Bloom et al., 2003; The Sentencing Project, 2022). More specifically, the WRNA itself is not intended to change client behavior, but to identify psychosocial needs that are associated with behaviors that get women into trouble and to case plan to those needs and strengths. It makes little sense to implement the WRNA in places where rehabilitation and desistance strategies are not woven into the organization’s mission, or with agencies that are not fully committed to delivering gender- and trauma-responsive strategies.

There are many gender-responsive programs and curricula that have been developed in recent years. While there are too many to adequately cover here, there are two resources that can help agencies evaluate and implement best practices. First, “Gender-Responsive Strategies: Research, Practice, and Guiding Principles for Women Offenders” is a hallmark report on research regarding justice-involved women and how gender-neutral approaches may impact them (Bloom et al., 2003). More recently, in late 2021, the National Resource Center on Justice-Involved Women published a comprehensive resource guide for agencies called “Adopting a Gender-Responsive Approach for Women in the Justice System,” which provides a comprehensive overview of current best practices, research, and programs for gender-responsive care (Fleming et al., 2021). This report provides a clear overview of prominent gender-responsive programs and practices, their effectiveness, and methods of implementation.

Importantly, the use of assessments and interventions alone are not enough if there are policies and procedures within an agency that undermine gender-responsive strategies. Resources are available to help agencies identify harmful practices and modify their policies and procedures to create spaces that are safe and supportive of justice-involved women, and to bolster the skills of staff working alongside them.

Again, the U.S. National Institute of Corrections (NIC) has been on the forefront of this work. For instance, the Gender-Responsive Policy and Practice Assessment (GRPPA) is one such agency-level tool that can be used at all levels of the justice system (NIC, 2023a). The Women’s Correctional Safety Scales Toolkit is another agency-level tool that focuses on creating safe environments for incarcerated women (NIC, 2022). NIC also offers a training for institutional staff called Safety Matters which trains staff to effectively communicate and safely manage situations with justice-involved women (NIC, 2023b). Such agency-wide changes require buy-in from both internal and external stakeholders and, like most policy changes, could take years to see positive effects.

Next Steps for Gender-Responsive Research and Programs

While significant work has been done around gender-responsive practices, there remain several areas in which research and practice remains incomplete and insufficient. Perhaps most pressing is the need for gender-responsive interventions to address members of the LGBTQ community (Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2016; Kahle & Rosenbaum, 2021). LGBTQ women and girls are disproportionately represented within the criminal justice system and have different, but overlapping, experiences with heterosexual and/or cisgender women. Many aspects of gender-responsive programming, such as trauma-informed practices, pertain to LGBTQ women and girls, but agencies and staff require additional training on LGBTQ-specific issues of cultural competence and responding to homophobia and sexism (Kahle & Rosenbaum, 2021).

Non-binary persons represent an additional unexplored area for future research around gender. Current tools are not validated on this population and little work has been done to identify unique needs of this community beyond being lumped in with the LGBTQ community in general. Current gender-responsive models remain focused on a gender binary. After all, this is how the justice system is set up with males and females in separate institutions and inconsistent practices related to transpersons (Sumner & Jenness, 2014). The future of gender-responsive research will need to focus on a spectrum rather than a binary to provide assessment and treatment that is truly catered to the individuals within the system.

* References available upon request

Emily J. Salisbury, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor and the Director of the Utah Criminal Justice Center at the University of Utah College of Social Work. She is trained as an applied criminologist and focuses her research on correctional policy, risk/needs assessment, and treatment intervention strategies, with a particular focus on system-involved women, gender-responsive practices, and trauma-responsive care. Her research publications have appeared in several top academic journals and edited volumes. As a result of her scholarship on behalf of women, she was awarded the Marguerite Q. Warren and Ted B. Palmer Differential Intervention Award from the American Society of Criminology Division on Corrections and Sentencing. Dr. Salisbury is a co-creator of the Women’s Risk Needs Assessment (WRNA) instruments that were developed through a cooperative agreement with the National Institute of Corrections. The WRNA correctional assessments are specifically designed to focus on the risk, needs, and strengths of system-involved women, and have been implemented in over 80 international and domestic jurisdictions. For five years, she also served as Editor-in-Chief of Criminal Justice and Behavior, a top research and policy journal focused on correctional rehabilitation. Lastly, Dr. Salisbury is co-author of the book, Correctional Counseling and Rehabilitation, currently in its 10th edition.

Megan Foster, MSW, is a doctoral student at the University of Utah’s College of Social Work. Her research focuses on gender-responsive programs, criminal justice, violence and victimization, resiliency, and trauma-responsivity. Previously, she was a program analyst with the American Probation and Parole Association, where she managed and supported a variety of grant-funded projects, including workforce and workload issues, tribal program, victims’ issues in community supervision, justice reform, and implementation of evidence-based practices. Prior to APPA, she worked as a direct practitioner and program manager in victims’ services and reentry programs. She has specialized experience working in reentry with women and families, as well as training and implementation of trauma-informed practices and programs. Megan received her B.A. in Women’s Studies from George Washington University and her Master’s in Social Work from Washington University in St. Louis.